本篇的英文是查Wikipediaa補充的

王璞的"肯尼亞的驕傲"

肯尼亞的驕傲

我一向所知的東非肯尼亞,大都來自丹麥女作家卡倫·布里克森那本《走出非洲》,這本書後來拍成電影,贏得好幾項奧斯卡獎,讓世人都接受了這位白人女作家筆下的肯尼亞印象:美麗壯闊,詩意盎然,人民馴良,生活幸福。

後來我讀了美國作家保羅·索魯的《暗星薩伐旅》,方知有另一個肯尼亞。它巔覆了我心目中美麗女作家的美麗肯尼亞,這個肯尼亞黑暗、落後,野蠻、原始,人民忿怨,生活悲慘。

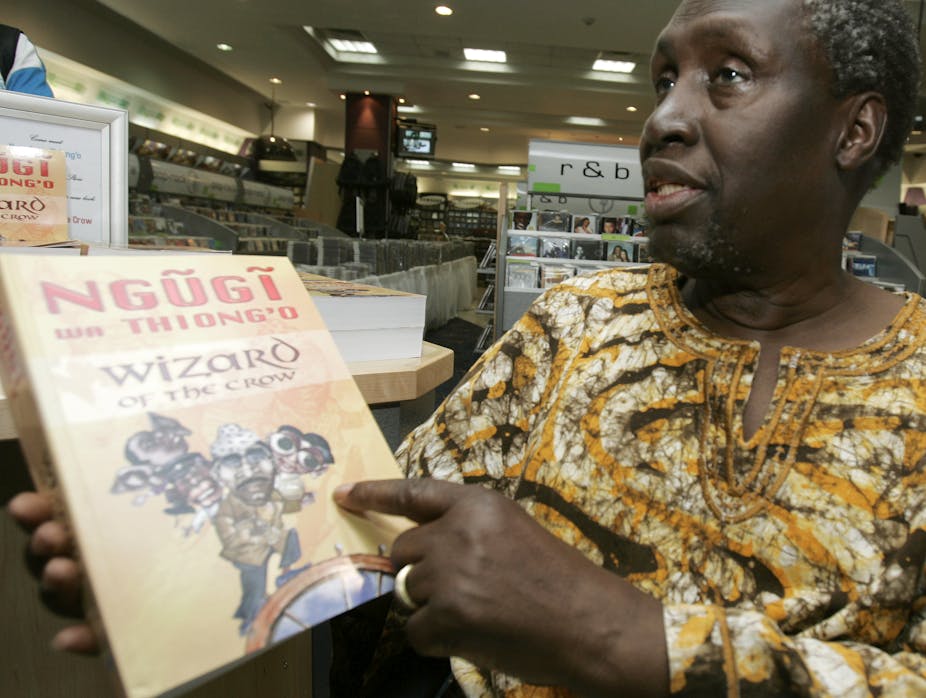

如今讀到美藉肯尼亞裔作家恩古吉·瓦·提安哥的自傳三部曲:《戰時夢》、《中學史》和《織夢人》,驚見更為真實的肯尼亞。它是前面那兩個肯尼亞的疊加。

怎麼形容我讀這部書的感覺呢?噢,想想奇美和奇丑疊加到一起是個甚麼景象吧,想想黑暗突被極光照射會是個甚麼效果,再想想「性相近習相遠」的兩個種族遭遇,一個已進入現代化,另一個還處於叢林狀況,會產生甚麼效應?

恩古吉生長於原始赤貧的肯尼亞農村,這農村其實并不偏遠,離首都內羅畢只有三十公里,但直到上世紀六十年代,村民們還停留在刀耕火種狀態,全部生命都耗費在怎樣生存上。恩古吉長到九歲還沒穿過一件衣服,十四歲上中學前沒穿過一雙鞋,這地方顯然不是世外桃源。不過由於信息閉塞,他和眾鄕親對外部世界的認知幾乎也是「不知有漢,無論魏晉」。

直到白人來了,先是德國人,後來是英國人,這些人帶來了醫療、文明和教育,也帶來了特權、強權和戰火。

他恨白人,因為他家的土地被白人奪走,白人臨駕於土著黑人之上,他們武器先進、科技發達、文化前衛,讓土著黑人毫無招架之力。

不過要到六十年後,當恩古吉已成為世界著名作家和學者、美國加州大學爾灣分校比較文學教授,跟他的祖邦在時空上都拉開了距離,他才得以從更深層次反思那一兩大文明和種族衝突的前因後果。身為親身體驗了殖民政府和獲立後黑人自治政府統治的肯尼亞精英,恩古吉已從自己批判殖民主義的早期作品走出來,也從自己魔幻現實主義的晚期作品蛻變,回歸淳樸,以純淨的文字和長者的智慧寫出他對這個世界的認知。

這是一部巨著,值得評述的方方面面很多,我在此只想講講給我留下最深印象的三個情節。

一是恩古吉九歲那年母親把他送入學校。他母親是文盲,在他父親的四名妻子中位居第三,被他父親抛棄,不得不獨力養活他和弟弟。可她認定了只有讀書才能改變命運,因為村子裡只有認了點字的人才能過上較好的生活。她跟兒子約法二章:她會盡己所能供他上學,而他則要保證盡己所能好好讀書。

母子二人都信守了諾言。母親拼盡全力供他上學,而本是讀書種子的恩古吉發奮讀書,在學校永遠名列前茅。

二是他十四歲昇中學時,黑人發動起義,組織遊擊隊與殖民政府展開血戰。恩古吉一名哥哥加入了政府軍,另一名哥哥卻加入了遊擊隊,他參加高中入學考試前夕,這兩個哥哥都回家跟他說加油。他們雖然站在對立的兩邊,跟弟弟說的話卻幾乎雷同:「我知道你馬上要參加考試了。我來祝你好運。你要盡力而為。知識是我們的希望。」

恩古吉沒有辜負他們的期望,他考上了肯尼亞最好的中學聯盟中學Alliance High School, ,成為那年整個地區唯一被那所學校錄取的考生。那是一所英國傳教士創辨的學校,教學宗旨擺明要從道德和智力方面為肯尼亞培養未來領導人。而後來的肯尼亞精英果然大都出自這所中學。恩古吉更成為肯尼亞的驕傲,是目前公認最有希望獲得諾貝爾文學獎的非裔作家。

不過最令我震撼的還是第三個情節。恩古吉上中學後,一直隱暪自己有個哥哥是遊擊戰士,他擔心這事敗露自己就會被開除。一天,他在返校路上遭遇軍事搜捕,被關押審查了一夜,嚴重違反了周未必須返校的校規。校長把他召去,他心想這下完了,不如豁出去,遂對校長說出遊擊隊哥哥的事,并聲言:

「我絕不會為你、為這個學校不認我哥哥。我哥哥是個好人,他要的僅僅是自由的權利。你們的丘吉爾狠揍希特勒,不就是想要自己人不受德國統治的自由嗎?您瞧,長官,我哥哥為自己人要求的是同樣的東西,他想要的⋯⋯」

他以為這下自己要被趕回家了,不料校長打斷他的話道:

「你當時穿了聯盟中學校服嗎?」

他說穿了。

「你可以走了。」校長說,「不過以後要當心,那些軍官不少是流氓。」

校長凱里·弗朗西斯是數學家,傳教士,參加過二戰,因表現英勇獲得大英帝國勛章,不用說是堅決效忠大英帝國的。但他沒為所謂的國家利益泯滅人性,他欣賞這名學生堅持自己理念的勇氣。

- Francis House: school's second principal Edward Carey Francis

多年以後,七十四歲的恩古吉回首這一往事,仍然對校長滿心感激,「在凱里·弗朗西斯眼里,」他寫道,「那些政客要麼是政治家要麼是流氓。拘押我的軍官雖為白人,也是一群流氓,因為他們居然有眼無珠,不識聯盟中學校服。」

讀到這裡,我好奇的是:那些軍官只是不識一所中學的校服,就被校長斥為流氓,校長要是知道有些政客叫人為了某黨某政權連阿媽也別識的話,會怎麼說?

Memoirs[edit]

- Detained: A Writer's Prison Diary (1981)[citation needed]

- Dreams in a Time of War: a Childhood Memoir (2010), ISBN 978-1-84655-377-6[citation needed]

- In the House of the Interpreter: A Memoir (2012), ISBN 978-0-30790-769-1[citation needed]

- Birth of a Dream Weaver: A Memoir of a Writer's Awakening (2016), ISBN 978-1-62097-240-3[citation needed]

- Wrestling with the devil: A Prison Memoir (2018) [86]

Five things you should know about Ngugi wa Thiong'o, one of Africa’s greatest living writers

Kenya’s most celebrated author Ngugi wa Thiong'o marked his 84 birthday on January 5. Having published his first novel – Weep Not Child – in 1964, Ngugi remains active in writing and teaching. His latest creative effort is Kenda Muiyuru (The Perfect Nine), a Gikuyu epic that was longlisted for the 2021 International Man Booker Prize. Kenyan academic and writer Peter Kimani sets out the five things you should know about one of Africa’s greatest living writers.

Who is Ngugi wa Thiong’o?

Ngugi wa Thiong'o is regarded as one of Africa’s greatest living writers. He grew up in what became known as Kenya’s White Highlands at the height of British colonialism. Unsurprisingly, his writing examines the legacy of colonialism and the intricate relationships between locals seeking economic and cultural emancipation and the local elites serving as agents of neo-colonisers.

The great expectations for the new country, as captured in Ngugi’s seminal play, The Black Hermit, anticipated the disillusionment that followed. His fiction, from the foundational trilogy of Weep Not, Child, The River Between and A Grain of Wheat, amplify those expectations, before the optimism gives way in Petals of Blood, and is replaced by disillusionment.

What sets Ngugi above and apart

African fiction is fairly young. Ngugi stands in the continent’s pantheon of writers who started writing when Africa’s decolonisation gained momentum. In a certain sense, the writers were involved in constructing new narratives that would define their people. But Ngugi’s recognition goes beyond his pioneering role: his writing resonates with many across Kenya and Africa.

One could also recognise Ngugi’s consistency at churning out high-quality stories about Africa’s contemporary society. This he has done in a manner that illustrates his commitment to equality and social justice.

He has done much more in scholarship. His treatise, Decolonising the Mind, now a foundational text in post-colonial studies, illustrates his versatility. His ability to spin the yarns while commenting on the politics that goes into literary production of marginal literature is a very rare combination.

Finally, one could talk about Ngugi’s cultural and political activism. This precipitated his yearlong detention without trial in 1977. He attributes his detention to his rejection of English and embracing his Gikuyu language as his vehicle of expression.

Works that best illustrate his thinking

It’s hard to pick a favourite from Ngugi’s over two dozen texts. But there is concurrence among critics that A Grain of Wheat, which was voted among Africa’s best 100 novels at the turn of the last century, stands out for its stylistic experimentation and complexity of characters.

Others consider the novel as the last signpost before Ngugi’s work became overly political. For other critics, it’s Wizard of the Crow – which came out in 2004, after nearly two decades of waiting – that encapsulates Ngugi’s creative finesse. It utilises many literary tropes, including magical realism, and addresses the politics of African development and the shenanigans by the political elite to maintain the status quo.

His lasting contributions to African literature

Without a doubt, Africa would be poorer without the efforts of Ngugi and other pioneering writers to tell the African story. He is also an important figure in post-colonial studies. His constant questioning of the privileging of the English language and culture in Kenya’s national discourse saw him lead a movement that led to the scrapping of the Department of English at the University of Nairobi and replaced by the Department of Literature that placed African literature and its diasporas at the centre of scholarship.

Ngugi is still active in writing. Among his recent offerings is the third instalment of his memoir, Birth of a Dreamweaver that looks back on his years at Makerere University in Uganda. This is the period when he published his novels, Weep Not, Child and The River Between, while still an undergraduate. Also at this time he wrote the play, The Black Hermit, which was performed as part of Uganda’s independence celebrations in 1962.

Presently, Ngugi is at work restoring his early works into Gikuyu, from the English language, which he bid farewell in 1977, opting to write in his indigenous language.

His work has been translated into more than 30 world languages.

沒有留言:

張貼留言