哈哈!或許也說得通:他們這專案不是有什麼"人文地理"等等: 某圖書館把索忍尼辛的《古拉格群島》列入地理類。

英國性v 台灣性

"I'm confused about Britishness these days," begins Smith.

Hello, My Name is Paul Smith

另外一字為Englishness,參考Sir Nikolaus Pevsner 妙著The Englishness of English Art (1956) 。

還可以參考Three Essays on Style (1995) (Ed. Irving Lavin) by Erwin Panofsky

聯想起許達然的『臺灣性』的說法。

詩

翻讀葉笛編《台灣詩人選集‧許達然集》---未收『車』(『李敏勇就認為他的一首詩(<車>)幾可涵蓋台灣史』)

可以寫的東西很多,不過花十倍或百倍的文字來談他的詩,不知是否對?

重溫錦坤兄2010年的一則筆記, 2010年3月16日 0314 2010

他的詩和文章沒發表的和為收入文集的,可能不少。

許達然《遠近三段》(《文學台灣》第6期,1993/April 頁106-07),其中第3篇"編籍" 可列入"官僚學(Bureaucratics,參考The complete Murphy's Law )的文學"----它還有對故鄉的情感。

編籍

自然堅持本籍,本人去戶政事務所辦手續,辦事員不知怎麼辦,請示主管,主管研究股情確定套牢不知怎麼辦,請示民政科,科長早隨市長去巡視,晚攜回許多問題不知怎麼辦,請示民正廳,廳長聽說聽訊去了,帶來許多強制處置的命令不知怎麼辦,請示內政部,查----從此台灣出生當作台灣籍,過去登記這裏現在當屬於這裏,查,遷入當按規定向各機關辦理,問題是許多人想盡方法要遷出,查,回籍還需些時日,而且也不一定准!

----

素描許達然:許達然散文集 中南方朔說: 他第一次見許老師是1980年代初於芝加哥 (不是師母說的60年代).....

***** ***** 我們上次去北埔.謝謝Ken和KJ. 那次許老師在學校有課.....

Dear HC,

清華大學停車費蠻貴的,四個小時下來會每部車交到200多元。

除非有教授可以免除我們的停車費,不然,

我建議停車在新竹市博愛街盡頭(在自來水公司門口,十八尖山的山腳下,地址:新竹市博愛街 1 號)有免費停車場,走路兩分鐘,就到達清華大學。

不管停車在哪裡,我們可以約早上九點或十點,在清華大學校園裡的麥當勞會合,有坐的地方,也可以喝咖啡、果汁,慢慢等人。

Ken Su清華大學停車費蠻貴的,四個小時下來會每部車交到200多元。

除非有教授可以免除我們的停車費,不然,

我建議停車在新竹市博愛街盡頭(在自來水公司門口,

不管停車在哪裡,我們可以約早上九點或十點,

翻讀RD 1990 AUG?

可能四點多就來上班

Published on Mar 3, 2012

導演:江偉華 劉嘉圭

故事是從東海大學一棟二十幾年的美術系館要搬遷開始,

我們走訪一些過去認識與素未謀面的人,

想從老建築到新建築中間找到一條氣味連貫線。

http://youtu.be/G73FOuPKUJ0

繆詠華分享了 Albert Camus 的相片。

大冬天的,我發現自己身上有個所向披糜的夏天。 ~卡繆

========

每次看到活得比較用力的人都會心頭一驚。

我也要真正活著。

========

每次看到活得比較用力的人都會心頭一驚。

我也要真正活著。

“Au milieu de l'hiver, j'ai découvert en moi un invincible été.”

― Albert Camus

Doris Lessing

Doris Lessing, writer, died on November 17th, aged 94

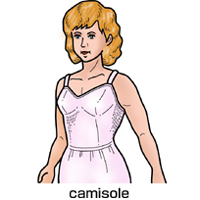

[名]カミソール:女性用袖(そで)なし下着.

|

For 30 years, by her reckoning, people had expected that she would get the prize. She hated expectation: that burden that made you a prisoner of circumstances and dragged you along like a fish on a line. The expectation when a child that she would behave, and not try to pull down her itchy stockings or burst into tears. The expectation that she would be a good wife (as she tried twice), pushing prams all day long, instead of leaving her two small children behind to start a new life. The expectation that the Communist revolution would usher in Utopia, when it was all “a load of old socks”. Why did people expect such things? Who had promised them? When?

Most frustrating was the public’s expectation that she, as a writer, would keep to one path. After the success of her first novel, “The Grass is Singing” (1950), packed in manuscript in her suitcase when she arrived, almost penniless, in Britain from Southern Rhodesia, she could have kept on writing about Africa. But in “The Golden Notebook” (1962) she plunged instead into the world of a woman’s dreams and mental disintegration, to wide dismay. In “The Good Terrorist” (1985) she expanded on her theory that acts of terror could be blundered into, rather than ruthlessly planned: again, alarums and confusion. Her five-book “Canopus in Argos” series (1979-83) ventured into science fiction, chronicling moral and ecological disaster on a planet, Shikasta, that was Earth in thin disguise. Many of her fans thought she had gone bonkers. She insisted that it was the best writing she had ever done.

Her name for that, for it wasn’t really science fiction, was “space fiction”: suddenly the old literary constraints were lifted, and she could write with breadth about universal themes. It was like sliding out of a stuffy room (she always noticed smells, whether of animal hide, lice, peas, unwashedness) to thrust her nose into cool fresh air, or running out into the bush of her Rhodesian childhood, with its miles of tawny grass shining in the sun. Or, in her London life, coming out of the flat where she had paced round and pecked at the typewriter all day to wander for hours through the night-time streets.

For too long she had played the game of being pleasant, fitting in. From childhood she was called “Tigger”, the bouncy beast, the jolly good sport. Good old Tigger, who underneath it all was in a rage of hatred against her mother and aching to run away as, at 15, she did. Another persona was “the Hostess”, so generous and talkative to the lefty and literary flotsam who crammed into her London flats, when inside she would be crushed from some unwise love affair or other, or just wanting to be alone. Everyone was a chameleon; hence “The Golden Notebook”, in which a woman’s life was narrated in discrete notebooks, emotional, political and everyday, which eventually tangled into one. Feminists seemed mostly to notice that it mentioned menstruation. They made it their handbook in the sex wars of the 1960s, which hadn’t been her aim at all.

Myth and truth

A small part of her was feminist, just as a small part was Communist

in the 1950s, and Sufi later. Every ideology collapsed into something

else, just as her frail family farmhouse of mud and thatch would fade

back into the bush in time. She never gave her whole self to anything,

except to one lover, “Jack”, in the 1960s—and to her third child, Peter,

whom she cared for until he died, of diabetes, this year. As a writer

she stood outside, “wool-gathering” and observing with sly eyes, like

one of her cats. Much of her heart, though, lay in Africa, and her

writing soared when recounting the labour of blacks, the easy bigotry of

little-Englander whites (like her parents) and the sights and sounds of

the place, from the smoke-mist of dawn to the rustling, creeping noise

at night that revealed itself as rain. Rhodesia was her “myth country”.She wrote “The Grass is Singing” to expose a truth: that white women could desire black men. It made a shocking scene when Moses, the cook-boy, was seen through the window buttoning up Mary Turner’s dress with “indulgent uxoriousness”. And she could spring the hard truth in dozens of smaller touches: describing a new mother as “a sack of bruised flesh”, or the “silky black beards” of underarm hair.

There was a true Doris, too, somewhere. This “aliveness” was where the stories came from, and it was buried deep. As she plumped herself wearily down on the doorstep to answer questions, that Nobel morning in 2007, she seemed to show an authentic, unbrushed side to the world’s press. But the real Doris was saying, as she had every day for decades, Run away, you silly woman, take control, write.

(中央社記者 楊淑閔台北 1日電)促修法落實 土地正義的 世新大學社發所助理教授、台灣農村陣線 發言人 蔡培慧昨傍晚車禍顱內出血,急救術後清醒,但腦壓大觀察中。

台灣農村陣線成員 許博任表示,蔡培慧昨天傍晚在苗栗竹南鎮上結束座談會活動後,綠燈走在斑馬線上時,被一輛綠燈左轉的小客車撞倒,因後腦著地,頭骨破致顱內出血,昨晚10時送抵林口長庚醫院手術救治,手術後,今天已清醒。

他說,醫生告知腦壓仍大,所以要先在加護病房住3、4天;肇事者是一名大學生,載著家人出門用餐,事發後很慌張,應是意外事件。

蔡培慧長年參與大埔農地等多件土地徵收爭議案,主張推動土地徵收條例修法,以落實土地正義; 許博任說,她發生車禍,引發許多人及媒體關注,希望大家為她祈禱,祝 她早日康復。