Babur

Map of Conquests of Babur

| 巴布爾 | |

|---|---|

| 蒙兀兒帝國皇帝 | |

巴布爾 | |

| 統治 | 1526年4月30日—1530年12月26日 |

| 繼任 | 胡馬雍 |

| 出生 | 1483年2月14日 東察合台汗國安集延 (今屬烏茲別克斯坦) |

| 逝世 | 1530年12月26日(47歲) 蒙兀兒帝國阿格拉(今屬印度) |

| 安葬 | |

身世[編輯]

巴布爾是成吉思汗(母系)和帖木兒(父系)的後裔,卽巴魯剌思氏。是突厥化蒙古人。母語為察合台語,曾以察合台文為自己立傳,名為巴布爾回憶錄。「蒙兀兒」即是波斯語的「蒙古」。巴布爾生於中亞的費爾干納谷地。

生平[編輯]

以11歲長子身份繼承父親的王位,在中亞錫爾河上游稱王,成功挫敗了來自四方的吞併陰謀,但後來巴布爾被烏茲別克人打敗,並逐出中亞,被迫放棄重建帖木兒帝國的理想,成為無家可歸的流浪者。1504年,趁阿富汗內亂之際,他率領300名部下攻入阿富汗,建立以喀布爾為首都的國家。1525年,巴布爾率軍進攻北印度。1526年,在第一次帕尼帕特戰役中,他大量使用火繩槍和大炮,擊敗由蘇丹易卜拉欣·洛提統帥的德里蘇丹國軍隊,易卜拉欣·洛提陣亡。在征服過程中,巴布爾以12,000人的部隊打敗了印度的10萬大軍。巴布爾接著攻取德里,並於4月27日在大清真寺的禮拜儀式上,宣布為「印度斯坦皇帝」,以阿格拉為新首都,建立蒙兀兒帝國,也結束了德里蘇丹國在印度320年的統治。1527年,蒙兀兒軍隊與以梅瓦爾的拉那·桑伽為首的拉其普特同盟在亞格拉以西的坎奴村進行決戰,拉其普特同盟戰敗。1530年,巴布爾在亞格拉駕崩,其子胡馬雍繼位為蒙兀兒皇帝。

李渝《賢明時代 提夢 (Timur(e)--鐵木耳 》台北:麥田,2005,pp.171~209

《巴布爾日記》=《巴布爾回憶錄》

維基百科,自由的百科全書

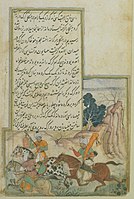

《巴布爾回憶錄》插圖之一。遠征森珀爾前,於蘇丹易卜拉辛廣場舉行頒獎典禮。

《巴布爾回憶錄》(察合台語/波斯語:بابر نامہ,直譯為「巴布爾的歷史」或「巴布爾的文字」)是帖木兒後裔、蒙兀兒帝國建立者巴布爾(1483-1530)的回憶錄,以豐富的內容和精美的插圖聞名。該書原由帖木兒王朝的慣用語言察合台語寫成,巴布爾將其稱為「突厥語」;阿克巴時期,朝臣阿布杜.拉辛於伊斯蘭曆998年(1589-1590)將其翻譯為蒙兀兒帝國慣用的波斯語。[1]

巴布爾是一位受過教育的帖木兒王子。他在回憶錄中反映出對自然,社會,政治和經濟學的興趣;生動的描述不止於自己的私生活,還涵蓋所處時空的歷史、人文和地理。該書包含各種主題,包括天文學、地理、治國方略、軍事問題、武器和戰鬥、動植物、傳記和家庭紀事、朝臣和藝術家、詩歌、音樂和繪畫、酒會、歷史古蹟、自我省思及對人性的探討。[2]

巴布爾本人沒有委託畫家為該書製作插圖,而是由其孫阿克巴於波斯語翻譯版完成後進行插圖繪製,期間花費十年有餘。阿克巴最早製作的4本插畫版《巴布爾回憶錄》於1913年開始印刷銷售,現存70多份微縮資料分散於維多利亞與艾伯特博物館、新德里國立博物館、大英圖書館、大英博物館、莫斯科東方文化國家博物館、巴爾的摩沃爾特斯美術館等地。[3]

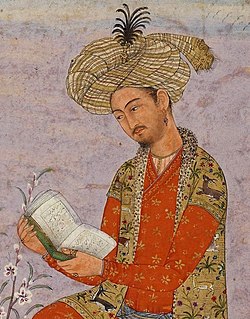

即便沒有留下生前的肖像畫,但為《巴布爾回憶錄》插畫的藝術家們一致將其描繪為圓臉、長鬍、頭戴特本,身穿長袖上衣與短袖外掛的形象。[4]

插圖

巴布爾、王子胡馬雍與隨從在巴格朗一帶休息,聽聞附近出現一頭犀牛。由於胡馬雍從未看過犀牛,一群人便興匆匆的前往察看。藏於維多利亞與艾伯特博物館。

巴布爾大軍從誇賈·迪達爾堡衝出。藏於大英博物館。

圍攻伊斯法拉。藏於巴爾的摩。

巴布爾參觀巴格朗附近的印度洞穴。藏於巴爾的摩。

參考文獻

^ Biography of Abdur Rahim Khankhana. [2006-10-28]. (原始內容存檔於2006-01-17).

^ ud-Dīn Muhammad, Zahīr. Babur Nama : journal of Emperor Babur. Hiro, Dilip., Beveridge, Annette Susannah. New Delhi: Penguin Books. 2006: xxv. ISBN 9780144001491. OCLC 144520584.

^ Losty, 39; British Museum page

^ Crill and Jariwala, 60

| Garden of Babur | |

|---|---|

| باغ بابر | |

Inside the Gardens of Babur in Kabul, Afghanistan | |

| |

| Location | Kabul, Afghanistan |

| Coordinates | 34.503°N 69.158°ECoordinates: 34.503°N 69.158°E |

| Created | 1528 |

| Founder | Zahir-ud-din Muhammad Babur |

| Open | 7 AM |

| Status | Active |

| Parking | Yes |

The Garden of Babur (locally called Bagh-e Babur, Persian: باغ بابر / bāġ-e bābur) is a historic park in Kabul, Afghanistan, and also has tomb of the first Mughal emperor Babur. The garden is thought to have been developed around 1528 AD (935 AH) when Babur gave orders for the construction of an "avenue garden" in Kabul, described in some detail in his memoirs, the Baburnama.

It was the tradition of Mughal princes to develop sites for recreation and pleasure during their lifetime, and choose one of these as a last resting-place. The site continued to be of significance to Babur's successors; Jahangir and his step-mother Empress Ruqaiya Sultan Begum (Babur's granddaughter)[1] made a pilgrimage to the site in 1607 AD (1016 AH) when he ordered that all gardens in Kabul be surrounded by walls, that a prayer platform be laid in front of Babur's grave, and an inscribed headstone placed at its head. During the visit of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in 1638 (1047 AH), a marble screen was erected around tomb of his foster-mother, Ruqaiya Sultan Begum,[2] and a mosque built on the terrace below. There are accounts from the time of the visit to the site of Shah Jahan in 1638 (1047AH) of a stone water-channel that ran between an avenue of trees from the terrace below the mosque, with pools at certain intervals.

History[edit]

The original construction date of the gardens (Persian: باغ, romanized: bāġ) is unknown. When Babur captured Kabul in 1504 from the Arguns he re-developed the site and used it as a guest house for special occasions, especially during the summer seasons. Since Babur had such a high rank, he would have been buried in a site that befitted him. The garden where it is believed Babur requested to be buried in is known as Bagh-e Babur. Mughal rulers saw this site as significant and aided in further development of the site and other tombs in Kabul. In an article written by the Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme,[3] describes the marble screen built around tombs by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in 1638 with the following inscription:

Although the additions of the screens by Shah Jahan contained references to Babur, Salome Zajadacz-Hastenrath, in her article "A Note on Babur's Lost Funerary and Enclosure at Kabul"[5] suggests that Shah Jahan's work transformed Bagh-e Babur into a graveyard. She states that a "mosque was built on the thirteenth terrace, the terrace nearest to Mecca; the next, the fourteenth terrace, was to contain the funerary enclosure of Babur's tomb and the tombs of some of his male relatives."[6] This transformation towards a proper graveyard, with an enclosure around Babur's tomb, points towards the importance of Babur. By enclosing Babur's tomb, Shah Jahan separates the tomb of the Emperor from others.

The only hint of the design lies in an 1832 sketch and short description by Charles Masson, a British soldier, which was published in 1842, the year the tomb was destroyed by an earthquake. One description of the tomb praised it, "although obviously-in a poor state of preservation, reveals fine workmanship in stone carving: high walls with lavish jali-work and relief decoration."[7] Mason described the tomb as being "accompanied by many monuments of similar nature, commemorative of his relatives, and they are surrounded by an enclosure of white marble, curiously and elegantly carved... No person superintends them, and great liberty has been taken with the stones employed in the enclosing walls."[8] Mason's sketch and Mason's description gives us the only modern view of how extravagant the tomb was.

Bagh-e Babur has changed drastically from the Mughal impression of the space to the present. Throughout the years outside influences have shaped the use of the site. For example, the Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme describes how by 1880, Amir Abdur Rahman Khan constructed a pavilion and a residence for his wife, Bibi Halima. In 1933, the space was converted into a public recreation space with pools and fountains becoming the central focal point. A modern greenhouse and swimming pool were added in the late 1970s.[9] Although the enclosure of the Babur's tomb is no longer present, Bagh-e Babur still remains a major historically important site in Kabul.

Over the past few years, attempts at rebuilding and reconstructing the city of Kabul and Babur's tomb have been undertaken. Zahra Breshna, an architect with the Department for Preservation & Rehabilitation of Afghanistan's Urban Heritage, argues that, “emphasis should be on developing and strengthening the partially forgotten local and traditional aspects, whilst placing them in a contemporary global context. The goal is to preserve the tradition without hindering the development of a modern social, ecological and economical institution.”[10] Planners also discuss the importance of ‘a revival of cultural identity’ in the development of Kabul.[11] These ideas seem to fall in line with the plan of Aga Khan.

The plan put forth by Aga Khan calls for the reconstruction of the Bagh-e Babur and includes several key components. The rebuilding of the perimeter walls, the rehabilitation of the Shah Jahani mosque, and the restoration of Babur's grave enclosure are all important parts of the rehabilitation of the garden and aid in the ‘revival of cultural identity.’ The perimeter walls, common throughout many Islamic cities, would provide for closure of the area. This enclosure of orchards is traditional in the area.[12] Also, the restoration of the Shahjahani mosque, a place for prayer and meditation for visitors to the gardens would be restored.

The biggest idea proposed is the restoration of Babur's tomb. The reconstruction of Babur's garden would bring about a unity fixed around the ruler responsible for the importance of Kabul and the restoration of the historic quarters would restore the pride of the citizens of the city. Architect Abdul Wasay Najimi writes that, "Restoration of confidence, pride and hope would be the main outcome in reintegrating the historic quarters in the mainstream rehabilitation and development of Kabul. This would have a direct impact on the revival of identity."[13]

Bagh-e Babur - UNESCO World Heritage Centre

https://whc.unesco.org › tentativelists

Nov 2, 2009 — From the top terrace, the visitor has a magnificent vista over the garden and its perimeter wall, across the Kabul River towards the snow ...

沒有留言:

張貼留言