歌、畫、故事 (TNN, 2021.12.28):

‘Search until you find a passion and go all out to excel in its expression’

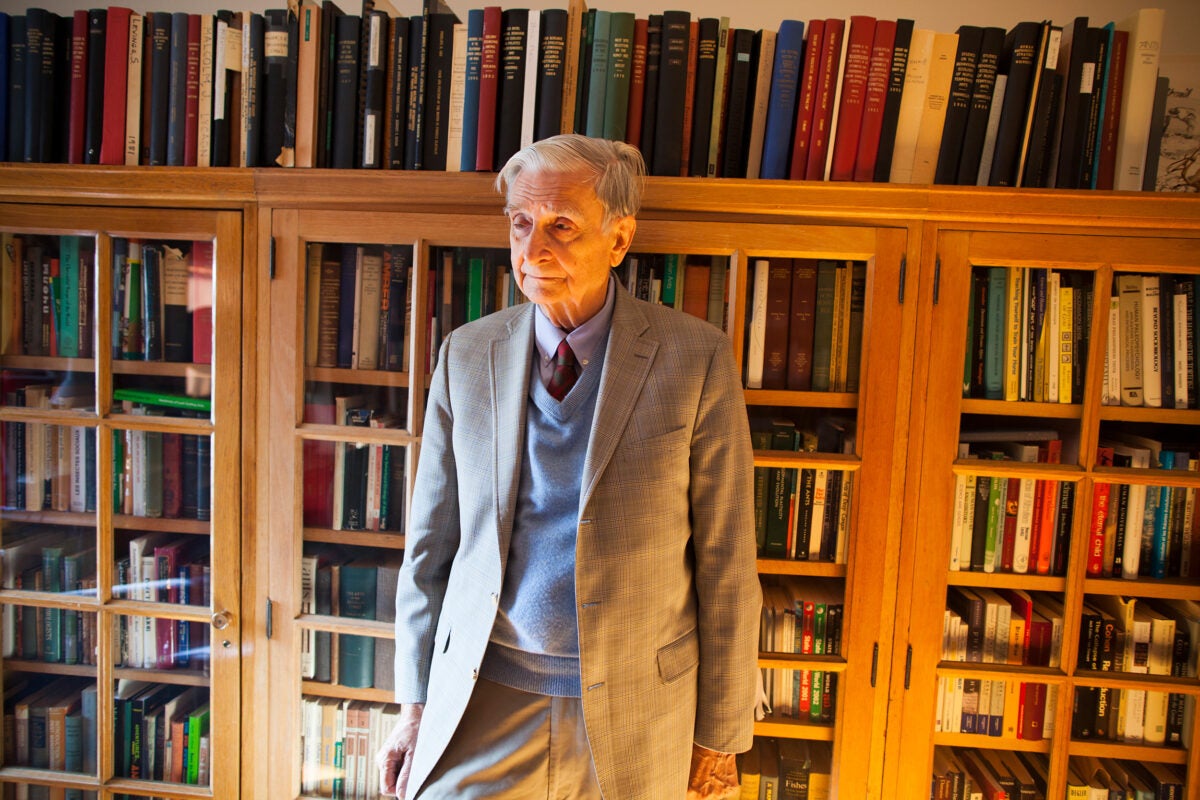

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

For E.O. Wilson, wonders never cease

Editor’s note: Edward O. Wilson, pioneering biologist, Pulitzer Prize-winning author, and Harvard professor for more than four decades, died December 26 at age 92. In a 2014 interview with the Gazette, he looked back on his life and work.

Edward O. Wilson, the Pellegrino University Professor Emeritus, was born in Alabama in June 1929. A boyhood immersed in nature and the world of insects provided an education he would build on through high school and at the University of Alabama, and then during graduate studies at Harvard, where he’s been since receiving his Ph.D. in 1955.

Wilson is probably best known for his groundbreaking insights on ants, but his research has extended deep into other realms of science, sometimes with provocative results. His theory of island biogeography, written with Robert MacArthur, examined how species rise and fall on isolated islands, both those surrounded by water and, more importantly for conservation today, habitat islands surrounded by different landscapes. His book on the biological roots of behavior, “Sociobiology,” touched off an academic row in the mid-1970s.

Wilson’s honors include two Pulitzer Prizes — for “On Human Nature” and, with Bert Hölldobler, “The Ants” — the National Medal of Science, in 1976, and the 1990 Crafoord Prize from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. He retired from full-time scholarship and teaching in 1996, but has carried on with research and writing.

Q: What guided you into the field of ant biology, and were there other options at the time?

A: There weren’t many options growing up in Alabama and I wasn’t even thinking that I would eventually have to choose a career. But I had chosen one just the same. I had become so passionate about nature and insects that I decided by my teens that I would become an entomologist. I thought probably what I’d do is join the Department of Agriculture and become an extension entomologist and advise farmers. Basically, I was willing to do anything to allow me to devote myself to entomology. I also got a lot from the Boy Scouts. That’s where I got my main education in an otherwise poor public school system.

When I arrived at the University of Alabama, I had just passed my 17th birthday. I found that the doors were open and the faculty there was very welcoming and supportive. They didn’t get many people, back there in the ’40s, who were interested in becoming an academic. Most of the biology concentrators were pre-med. I graduated shortly after my 20th birthday, then went on to get a master’s degree, and then to the University of Tennessee — that was getting pretty far north for me — to join their doctoral program. I had a wonderful professor of botany named Jack Sharp. He was known nationally for his research on plants. In late 1950 or early 1951, he wrote from Knoxville to his friend Frank Carpenter, who was chairman of the Biology Department and professor of entomology, and said, “This kid does not belong here, he belongs at Harvard.” He did me a tremendous service with that letter.

I’d already visited Harvard in the summer of 1950, mainly to see the ant collection and visit a graduate student working on ants with whom I’d corresponded. I had made some added connection there and met one of the professors in the Biology Department. The result was that Harvard wrote me, saying that if I cared to apply, it’s very likely I would get a teaching fellowship and be admitted. And I did just that.

In the spring of ’53 I was overjoyed to receive a junior fellowship [of the Society of Fellows], and the ability to go anywhere in the world I wanted, with all expenses paid, to do anything I wished. The only oath asked of the new junior fellows at the dinner at Eliot House was that they do something extraordinary. What an incredible charge to give an ambitious young man or woman: “We don’t care what you do, what field you go into as long as you accomplish something — as a junior fellow — extraordinary.” I decided I would do that.

Q: What was it about entomology that attracted you? Was it the ability to explore the outdoors or something about the insects themselves that drew you?

A: I have only one functional eye, my left eye, but it’s very sharp. And I somehow focused on little things. I noticed butterflies and ants more than other kids did, and took an interest in them automatically. Even at the age of 9 in school in Washington, D.C., I was reading about insects through all the National Geographics. And there was one article in 1934 entitled, “Stalking Ants: Savage and Civilized.” It happened to be by the man [William M. Mann] who later became the director of the National Zoo, and he got his Ph.D. here at Harvard. It just knocked me flat when I read about that.

Even though most of the species he depicted were found only in other countries, especially in the tropics, I was soon out watching ants, trying to find the ants he mentioned in the book and going to the national museum. I was also developing a passion for butterflies. I had a net, which my stepmother made for me from a coat hanger, cheesecloth, and a broom handle. So I was off and running by the age of 10. I was trying to read books on entomology. They were over my head, of course, but I had the ambition to learn what I could when I could. And all through my teen years, as I was advancing up to Eagle Scout in Alabama, I was focusing on natural history, including ants and butterflies and snakes.

Q: Did you ever give your selection of ants a second thought? Did you ever, in a discouraging time, ask, “Why didn’t I do something easy?”

A: Ants are easy. I had been collecting them all over the state of Alabama and elsewhere and identifying [them]. I had already, in high school, made friends with the very small number of ant experts in the United States, exchanging specimens and getting advice and so on. It seemed terribly easy to me from the beginning.

E.O. Wilson (1929~2021)

What I wanted to do when I got to Harvard was get a much broader background. This was helped substantially by contacts in the Biology Department and also the Society of Fellows. I had the pleasure of having conversations with other junior fellows, who included people like Marvin Minsky and Noam Chomsky, and got to meet people like T.S. Eliot and Robert Oppenheimer. It was just amazing. You could talk with these exceptional people and grow in breadth and confidence. But the dream that kept returning was to go to the tropics and study the ants of the rainforest. I left almost as soon as I became a junior fellow.

In 1953, I was off to Cuba and Mexico, a paradise for me of tropical forests inhabited by hundreds of kinds of ants. And then I came back and finished my Ph.D. I soon informed the chairman of the fellows, the historian Crane Brinton, that I was on my way to New Guinea, to all the other archipelagos of Melanesia, and I would try to cost the Society of Fellows as little as possible. And off I went. It was there that I collected ants and studied rainforests and thought about ecology and took long, sometimes solitary trips through the forests. I began to develop ideas about how ants had gotten into these distant places and how they’d evolved.

In later years I realized that what I was doing is what Germans call wanderjahr, the year of wandering. It is a German expression for young men who were expected to leave the village. They’d mature and go off to another village to learn a trade. And this is what people like Darwin, Philip Darlington, here the curator of entomology, and Ernst Mayr had done. As young men, they were in the tropics soaking up all the raw information and experience of what the natural world is really like, and forming ideas about it. I came back in 1955, married, and was bursting with ideas about what I could do in science, using ants as my principal group.

Q: And did that trip lead specifically to any of your noted theories? Did the theory of island biogeography come from there?

A: That came straight from there. When I met Robert MacArthur in the late ’50s, we were both young professors, deeply worried about the status of our field, which was ecology and evolution. It was a golden age of biology, but of molecular and cell biology. It looked as though ecology, systematics, and biogeography would just be relegated to third-line status as far as universities like Harvard were concerned.

MacArthur and I hit it off very quickly. He had mathematical modeling ability and I was already publishing substantial papers on Asian and Pacific ants. We put our heads together and … developed the theory of island biogeography. It was immediately successful, because it hooked up ecology to conservation biology.

The world consists of islands, the reserves and the parks and the remnant patches of forest on the mountainside are islands. We saw the [theory as a] way to deal with the fate of species that were essentially confined to what we call habitat islands.

‘I haven’t changed since I was a 17-year-old entering the University of Alabama. I’m still basically a boy who’s excited by what’s going on.’

Q: As forests have become more fragmented and habitats have become smaller, has the theory become more relevant?

A: Oh, vastly more relevant. It’s one of the foundation pieces of conservation biology: how to understand why there are a certain number of species in a forest, maybe a forest on an island or maybe a fragment of forest on the continental coast. How to analyze it, find out what’s happening, to look into particulars like how often species reach the island, how fast they’re likely to be going extinct, how fast they might be evolving to create new species. All those factors are seen as basic in evaluating the status and the value of a particular reserve.

Q: Clearly you’ve made several seminal contributions to science — is there one that you feel proudest about or view as your crowning achievement?

A: By 50 years from now they’ll say, “Look, here’s the Museum of Comparative Zoology, where that fellow … what was his name?” [Laughs] I’ve had several “aha!” moments. Certainly one was the theory of island biogeography that came together in conversations with MacArthur.

The second one hasn’t been noted very much but it was one of the reasons I got the National Medal of Science at a very young age, in 1976. That’s the development of pheromone biology and studies of social insects, and also the very first theory of pheromone molecular evolution and dynamics. I published the theory in 1962. That was done with another colleague right here at Harvard, Bill Bossert. Bossert and I produced the first basic conception on what would be the optimal nature and size of pheromone molecules and how one could predict the rate and extent that they spread and how all this could be adaptive for the species. Oddly, pheromone research hasn’t advanced very much. I have a feeling the reason for that — the theory I worked out with Bossert was not given much attention — is that about the only place people produce pheromones is in their armpit and that is not very interesting. [Laughs]

Third happy — aha! — moment. The one time I couldn’t sleep at night was after making the first fire ant pheromone discovery. I did it here in the lab with fire ants. I decided to use a trail pheromone. When I hit the tiny gland that produces it in the rear part of the ant, I got a completely surprising response. The ants followed it, but it activated them in a variety of other ways. It excited them. It caused them to start communicating with other ants that followed. The fire ant trail substance was the first glandular pheromone source discovered in insects, or at least in social insects. Subsequent research showed that it was a blend of pheromones. So what I was looking at was a variety of messages sent simultaneously among the ants.

One aha! moment, sort of a lowercase aha!, was the discovery and description of the first ant of Mesozoic age, in other words, ancestral to modern ants. I knew that ants must have originated in the age of reptiles, back in the Mesozoic, but the earliest specimens we had were from the age of mammals, back 60 million years. So all of us were waiting for the discovery of a Mesozoic ant, when two of them were found in one piece of amber. I’d like to tell you it was found on an upper branch of the Amazon River, but it wasn’t; it was on the New Jersey shore [laughs] — in a 90-million-year-old deposit of amber and woody materials. Out of that came a perfect specimen in a perfect piece of amber, clear as glass with two ants in it. That was a thrilling moment to put it under a microscope and say, “OK, guys, we’ve already made it to 60 million and now we’re going to go all the way back to 90 million.” And the darn things fitted exactly how we predicted if ants evolved from wasps.

Q: When was that?

A: That was the late ’60s.

And finally, a drawn-out aha!, the one that really caused quite an uproar here at Harvard, was when I was building the field of sociobiology, first with the book called “The Insect Societies,” in 1971, and then “Sociobiology: The New Synthesis.”

Sociobiology was far more than what many of its critics wanted to call it: just the belief that human beings have genetic-based instincts. Sociobiology is the systematic study of the biological basis of social behavior in all kinds of animals, and that’s how I developed it in those two books. It was very simple. I did say that maybe the same principles that we’re learning from comparative studies of social behavior and the evolution of social behavior in animals might apply to human beings. But if it applied to human beings, the only way it can be applied meaningfully is that human beings have instincts. We have drives that are inborn, that people inherit, and there may be variation among people. I stepped into a minefield by finishing this big book, “Sociobiology,” with a chapter saying how it could be applied to people. I tried to be cautious. I should have been more politically careful, by saying this does not imply racism, it does not imply sexism, I’m not trying to defend capitalism, so don’t drop the world on top of me. If I’d added that in the book, then I might have gotten off a little easier.

In the ’60s and ’70s it became almost dogma — it was a dogma — to believe that the human brain was a tabula rasa, a blank slate. I don’t think scholars in this generation, even those of middle age, can appreciate how stern was the prohibition against believing that human behavior was influenced by genes in any manner whatsoever. The only acceptable view was that the brain was a blank slate and what humanity does and humanity feels and what societies end up becoming is strictly a matter of choice and is determined by our history, particularly by the culture we’re born with. We can design a much more perfect society if we use our reason and train the brain accordingly. That was the belief in the social sciences. It was also the belief of the — how shall I put it — the far left among some scientists, including two of my more notable colleagues here at Harvard, Richard Lewontin and Stephen J. Gould. They were really incensed that a colleague of theirs would deviate so far from what was the needed ideology, the political ideology, to make social progress. And they were marvelously sophisticated Marxists, with well-reasoned ideas of how to blend socialism and biology.

Harvard faculty and the students — partly as a result of the convulsions of the ’60s — were far left and very few would openly defy them. Being from Alabama, I was expected, I think, to be a conservative. And I can tell you now, thinking back, I was really neither. I was at neither end of the spectrum. I was an innocent sociobiologist.

I thought that this was a great idea. I saw all sorts of possibilities for building a sociobiology that could then be picked up by social scientists. And I really was so naive as to think my colleagues in the social sciences would be grateful to me [laughs] for having provided them with a whole different armamentarium for their theories on the origins of human behavior. What I got was mostly buckshot [laughs]. That has changed now, but that was the aha! moment.

Q: Were you surprised at the response? Did you have no idea it would be controversial?

A: I had no idea. I really wish I could say I knew it was coming, but it really blindsided me. And it took me a while to figure out how to respond.

Q: Did you have an emotional reaction? Did you feel hurt or was it more intellectual?

A: It was more intellectual. The first time I saw one of these counterattacks appear in The New York Review of Books, I saw I was going to win this one. With the reasoning and evidence, I felt confident. It was science versus political ideology.

But I really was upset at being called a racist, promoting racism and sexism. I was accused of trying to reintroduce a retrograde, outmoded, dangerous philosophy. There was nothing in “Sociobiology” to suggest such a thing. The words had to be taken out of context and tweaked.

On one occasion, I had a little mob in Harvard Square parading and protesting and holding placards demanding that Harvard dismiss me. On another occasion, when I was to give a lecture at the Science Center, a crowd of protesters gathered at the entrance with signs and shouts and chants and so on. I was ushered in through the rear by University police. My class was disrupted at least once. Not seriously, but yeah, that’s annoying. Looking back at that now, it was a very strange period.

This created a sensation, but at least students were exposed to new ideas. I say to myself to this day, “Is this not what a university is for?” This is what a university is supposed to be doing.

Q: How about mistakes along the way? Are there things that you regret or things you might have done differently?

A: That was one of them. When I was writing “Sociobiology,” if I had to do it over again, I would have written a solid piece in that infamous final chapter and said that it really tells us nothing about the best political system or correct ideology. This is just knowledge, through which we can acquire a view of the human condition. We can acquire what we did not have before and this has to be useful.

Q: What is the strongest argument today that your thoughts on sociobiology were right? I hear a lot of things related to the obesity epidemic, people trying to explain why we behave the way we do.

A: That book came out in ’75, and in the early ’80s, the field of evolutionary psychology spun off. My colleagues working in the social sciences and psychology who created evolutionary psychology avoided the word “sociobiology” — some of them told me this. They wanted to use another word that wouldn’t be tarnished from the beginning. To this day “sociobiology” is only sparingly used as an expression because people are still a little afraid of it. In 1978, in the midst of all the tumult — people smile when I say “tumult” in talking about academics hitting one another with beanbags; it really wasn’t quite the same as a civil war — I said to myself, “I have to write a book that will do what I should have done in ‘Sociobiology.’” That is, explain how I view human behavior and what the applications of sociobiology could be and what the possibilities of it are.

I think that it’s fair to say the work I produced was the founding book of evolutionary psychology, although it wasn’t until the next decade that the term evolutionary psychology began to be used. But the book, “On Human Nature,” in 1978 won a Pulitzer Prize and, as we say in a Southeastern Conference football game when our team scores on the opponent’s field, “That has a way of quieting the crowd.”

Q: What do you think of an entomologist winning two Pulitzer Prizes? Is that something you could have envisioned when you were a young boy?

A: I think it’s bizarre [laughs]. It was luck.

The second Pulitzer was a big, comprehensive book Bert Hölldobler and I put together. Bert and I worked together for a dozen years in the laboratory section of the MCZ [Museum of Comparative Zoology] and our collaboration was very fruitful. We had different talents and different approaches. Bert brought in rigorous methods of investigation by stepwise experimentation. I brought into the mix the scientific natural history. I knew the ants; I knew what was interesting to look at. We published a lot. And then Bert couldn’t get enough of the support he needed and the University of Würzburg offered him a million dollar prize to create anything he wanted to create. And so off Bert went. But before he left, we said, “Look, between the two of us, we know everything there is to know about ants.” Nobody could say that today because the field, myrmecology, has grown exponentially, but you could say it then. And we said, “Let’s write a book that has everything known about ants.” And to my astonishment, it was given the Pulitzer. It was also the only book of science-meant-for-scientists to win the prize. We didn’t write this for the literary world — we wrote it for scientists. But we did our best job of writing and illustrating and so on.

Q: What is your philosophy of writing? Do you have writing habits? Do you write every day?

A: Every day.

Q: Do you love it or is it a chore sometimes?

A: I love it. You know, like a shark, unless you swim you sink? I have that feeling. I remember one of the great pianists once said about practicing, “I miss a week of practice and the audience notices. I miss a day, and I notice.” It’s just what I love to do. I love the research, I love the study, I love the quiet thought, and I like writing. I just write or conduct research every day. Always there’s something new to write about.

Q: Do you do it here or do you have a study at home?

A: Mostly, I do it at home now. And I write longhand on yellow, lined legal paper and Kathy Horton is the reason I can do that. She’s been working with me 47 years and she knows everything, knows everybody.

Q: Safe to say she’s deciphered your handwriting by now?

A: She has. There have actually been occasions where I couldn’t decipher what I’d written, at least a word or two, but she could translate it. She’s like having a cuneiform expert help you out with Assyrian tablets. She is really very good at what she does and it has allowed me to move smoothly over a long period of time.

Q: What is most exciting about your field right now?

A: I haven’t changed since I was a 17-year-old entering the University of Alabama. I’m still basically a boy who’s excited by what’s going on.

We are on a little-known planet. We have knowledge of two million species, but for the vast majority we know only the name and a little bit of the anatomy. We don’t know anything at all about their biology. There is conservatively at least eight million species in all, and it’s probably much more than that because of the bacteria and archaea and microorganisms we’re just beginning to explore. The number of species remaining to be discovered could easily go into the tens of millions.

We will in time see a surging interest in and support of the area of biodiversity studies. I believe Harvard should be the world’s leading university in this field and in those branches of ecology and conservation biology that have biodiversity studies as a foundation. Harvard should be in a position to lead, because Harvard has the largest private collection of plants, animals, and fungi — three of the major groups — in the world. It has one of the finest libraries in the world. It has a great tradition, going back to Agassiz, of major studies and acquisitions of major collections. It’s obvious that this is the place to build the discipline … so that Harvard could be one of the universities, one of the rare universities, in the front rank of both of the two big divisions of biology, structure and history.

Q: How do you feel about the future of biodiversity on the planet? Are you optimistic or pessimistic?

A: I use an expression John Kennedy used at least once about the future generally: cautiously optimistic. I’m now advising on reconstruction of a national park in Mozambique, the Gorongosa National Park. I’m working with a group on the Gulf Coast to create a new park at Mobile and the Delta, which will be the biologically richest in America. This is how I’d like to see progress achieved, step by step. It’s what I’m going to be involved in, as much as I’m able, in the years I have left. We have an opportunity. We still can put aside a large portion of the world in reserves of biodiversity. But that potential is shrinking steadily and we really need to do something now. This is where Harvard can play a major role. If it becomes policy in a sufficient number of nations, then there are plenty of reasons for optimism. But if we keep going the way we are now, we’re going to lose a large part of biodiversity by the end of the century.

Q: What lessons can a young student starting out today, looking at your career and thinking, “I want to make an impact like that” — what lessons can he or she extract from your life?

A: It almost sounds trite, you hear it so often, but you don’t see enough of it in college-age students, and that is to acquire a passion. You probably already have one, but if you haven’t got one, search until you find a passion and go all out to excel in its expression. With reference to biology and science, do the opposite of the military dictum and march away from the sound of guns. Don’t get too enamored by what’s happening right at this moment and science heroes doing great things currently. Learn from them, but think further down the line: Move to an area where you can be a pioneer. That kind of opportunity is everywhere in science and especially in biology, including biodiversity studies and ecology.

Q: Did you ever think of leaving Harvard? You’ve been here many years and had lots of victories. What kept you here all the time?

A: I like being at the world’s greatest university with the world’s best insect and ant collections. Believe it or not, however, during the height of the anti-sociobiology furor, I started looking around at other universities where I could work in peace.

I have to confess, here for the first time, I had a fantasy of going to Texas A&M, where I could sit peacefully in my lab working, with good graduate students, while watching cadets marching by outside [laughs].

But I never really came close to leaving Harvard. It’s just too great a place.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.

台北書緣 (2)。(美) 劉照男《山中燈火入夢來》(A Light on My Path, 2021,回憶錄 )與室友吳福助教授

https://www.facebook.com/hanching.chung/videos/620880152662338

----

所謂的管芒花是一種芒草,但其實在相同的貧瘠環境條件之下,會有多種不同的植物共域,它們不僅形態相似,名稱也易於混淆:蘆花、葦花、芒花、荻花等,

https://www.facebook.com/hanching.chung/videos/4193767490634026

談點我的同學蔡禎騰博士和李基正先生

談點我的同學蔡禎騰博士

我的一位東海學長跟我電話談了近一個小時,其中談到我的同學蔡禎騰博士。學長提起有些人不喜歡蔡博士再次當上副校長,說他嗜酒,甚至跟學生喝起來,經常醉酒。我跟學長說,家父是酒中之徒,而我與蔡先生的一些交往中,沒有聞到酒味。

我覺得東海有誹謗之風,猶來已久,這次或許也是加上一樁。

我現在倒述一下我跟蔡先生的一些交往。

我在2周前發現蔡先生開始使用Gmail,而Gmail是我多年前開始使用的,比較知道它的功能。所以幾天前在某Facebook交友社團中發脾氣罵人時,我知道蔡先生不是member,聽不到指責他過握的聲音,就轉寄給他。

漢卿 (sic) 兄

我開才收到臉書簡訊,得知沈金標兄在校友總會臉書上說我主張學校募款與校友總會無關,本人看了極為驚訝。我不曾說過這種話,也不會有此想法。請沈兄諒察。本校募委會組織章程中明列校友總會長為當然委員,此即對校友總會之依賴及敬重,我是本校募委會執行長,自然不會說出違背學校章程所定之精神的言語。我手機是0931-409-xxx.如果仍有疑慮,沈兄歡迎隨時來電。我因無沈兄通訊方式,亦尚未加入校友總會臉書會員,一時無法回應沈兄意見,勞駕你待轉為荷。

弟 禎騰

沈先生接到此信,寫信抱歉並將一組我與他談論的文拿掉。

----

我簡單寫一下我與蔡同學的交往。

我在建築研究所和化工系兼過課,獨獨沒回工工系兼過課。約1996年我回系上演講,感謝劉教授幫忙,可以住招待所。那晚蔡先生在某高爾夫球練習場展現他的力道。

在2003年我系創立40周年出版了一本圖文並茂的系史。蔡先生轉送一本給我,感謝我80年代初捐錢給系上買電腦。

我在2012年12月得知同學李基正兄獲獎特別發表”一些書: 感謝蔡禎騰和李基正—回憶一下2008年10月的盛會”

歌

Richard Strauss - Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30

《葉珊散文集》中的東海記憶。東海相識50年 (1975級及1976級建築)

****宿舍

大度山居歲月 羅時瑋/第17屆建築系

民國60年夏天尾巴時,是新生入學第一天,就在大學前站牌處走下客運車,眼前幾落平房麵館和彈子房,圍著一小方黃土石子地坪,對面就是東海大學入口。越過兩線道的中港路,路邊都是碎石渣,來到校門口,設有警衛室,旁邊還豎起一支高高的貼黃磁磚的十字柱。

走進蟬聲聒噪的鳳凰林蔭道,傍著一條彎彎小河溝,在河溝沒入路面時,左右兩邊就是男生宿舍入口了。說是入口,也沒設門禁,就從5棟末端拐進去,走過1棟宿舍背後,迎面是一片草坪,草坪後是大屋頂的男生餐廳,往左轉入宿舍區,在9棟樓下川堂領完用品,前面是個粗放的院子,幾棵大榕樹,加上紅磚間砌的曬衣場,四邊是錯落配置的長條宿舍棟,住房部份兩層樓高,隨著坡地局部設有地下層,作浴廁、鍋爐間、儲藏室使用。

找到721寢室,見到了從台北、高雄、台中來的同系同學,興奮地互相自我介紹。每間寢室住六人,裡面都是實木家具,有兩人合用的大書桌、兩人用的櫥櫃以及雙層床,寢室整個面寬都開大窗戶,門口上方也有氣窗,通風採光都很良好。

到傍晚時,端著臉盆到浴室洗澡,赫人發現浴室沒門,還靠窗很近,雖是毛玻璃窗片,不怕被從外面看見,但浴室裡明亮得很不習慣,戰戰兢兢地洗到一半,幾個學長竟然赤條條地加入,大家坦誠相見,生平第一次如此集體淋浴(一般男生應在入學前就在成功嶺受訓時領教過了,但我們建築系要到一年級暑假才到成功嶺受訓),真是新生特別的震撼洗禮。

這可能是東海男生的革命情感源頭,天天如此共浴,穿上衣服還能假裝不認識嗎?7棟在地勢高的一區內,有時水壓不夠,洗澡到一半會停水,只好濕噠噠地再披上衣服,手腳還沾著肥皂泡,端著臉盆越過約農路去下方的宿舍洗,還好多半發生在夜間,遇見認識女生正好路過就裝作沒看到。

宿舍房間的尺寸是刻意設計的,長向可擺足三張床的長度,短向入口這面,門並非設在正中央,門的一邊可容一張床長度,另一邊容得下一個床寬,也就是說房間是以床的長寬模矩設計的,桌櫃尺寸也按此模矩製作,容許有彈性的安排方式。所以在後來每學期開始,室友們就共同討論如何擺放傢俱,每學期都通過共同協商而重新調整,每間寢室的內部擺設都各個不同,以今天的術語來說,就是生活民主的落實囉!

六個生活習慣很不同的人怎麼擠一起過日子呢?有人想熄燈睡覺,有人還要開夜車,有人整天窩在寢室照鏡子剪指甲,有人終日不見人影襪子亂丟臭死人,所有累積的衝突與不滿,平時就靠個人溝通本領,然後每學期重新組寢室換夥伴,再來就按個人需求調動傢俱,所有生活上的齟齬,就在宿舍房間設計的彈性裡化解。

另一個東海特點是勞作制度,大一大二都要做勞作,每天清晨與中午固定時間,要一起掃落葉、洗刷噁心的廁所,還到餐廳後頭大水槽清洗油膩膩碗盤,但惱人的是必須清早點名,缺席次數太多就不及格,勞作不及格須重修,要及格才能畢業。建築系夜間趕圖,通常都爬不起床做勞作,常只好再熬到天亮,做完勞作再回寢室睡覺。

大一基本設計有一次是石膏製作,老師先運一車黏土給我們做粗胚,那一周我們寢室到廁所之間的走廊地面都滿是黃泥巴,教官氣極了,找人來清洗。但次周要翻模灌石膏,寢室到廁所的走廊又立刻變得白花花地一層石膏渣,教官都幾乎瘋了。建築系常要開燈通宵趕圖,60燭光燈泡不夠用,只能改裝200燭光燈泡,電源常因此跳電,整排宿舍瞬間黑暗,一般保險絲很快就燒掉,後來有人就用粗鐵絲來接,反而比較耐用。

二年級時換到823寢室,就住在教官寢室隔壁,那年大家決定要乖一點。開學後聽說將有流星雨,室友們就想說系主任漢先生總要我們做些新鮮事,要如何趁機會來點新鮮呢?大家想到去年勞作工頭盛姐人很好,我們來去找升上大四的她、跟她寢室結為姊弟寢室,於是一行無聊男子就走向女舍721寢室,就在通往音樂系館小徑上方,我們在樓下叫她,報出我們的友誼信息,學姊們倚著陽台欄杆笑得好燦爛。

女生宿舍房間大小跟男舍差不多,但開整片落地窗,外面有陽台。那時全校才七八百人,女舍一樓很多空著,作為穿越空間,男生在宿舍區內從小圓環到女生餐廳之間都可自由走動。但巧妙地隨地勢而分區圍出小庭院/曬衣場,南北向多圍白牆,東西向圍以紅磚透空牆,只供裡面人進出,外人不得而進,動線規劃得巧又嚴密。整個宿舍區以高牆圈起,裡面就是一座沒有賈寶玉的大觀園。

東海宿舍形式簡單,走廊欄杆就是開放式的實木條搭接,走廊也直直通到底,甚至女舍樓梯多是直通樓梯,而且宿舍都用天然材料,白牆灰瓦紅磚檜木,背景統一,無論外人如何誤闖禁區,幾乎毫無藏身角落,立刻就被發現,因此是最具防衛效果、又適度開放的管制空間。

那時候女舍沒通報系統(負責管理的張怡慈先生住在宿舍區中央)、大家也沒手機,男生到女舍找人,可在門口託走過女生幫忙,告訴她要找誰、第幾寢室,她就一定幫忙找到她,若正巧人不在,被託的女生會再走出到門口告知人不在。當然,在以前小圓環那裡,也有男生站在對方寢室下方呼叫名字,被找的女生就大聲回應,跑出陽台說再等一下,有些酷哥還吹聲口哨,裡面女生就知道了。從7棟二樓下來到5棟之間有一小橋相連,從站在圓環的男生眼睛高度,橋面約高出半層樓,女生過橋時翩翩身影,總像仙女下凡一般。

我們有時在系館趕圖到四點快天亮前,讓腦袋休息一下,做張小卡片寫些祝福話語,摸黑到女舍往音樂系館出來的必經路上擺好,然後回寢室休息,一覺醒來就聽到女舍傳來,某某女生撿到那張卡片,又已經瘋傳到哪個女生手上了,這就足夠讓我們快樂一整天。

大三住到1402,這間寢室裡面還有一扇門,我們好奇推開,原來通往鍋爐間,還有一個水龍頭與水槽,大家興奮之餘決定一起來開伙。有室友就從家裡帶來鍋碗瓢盆,有人負責到老師宿舍區小市場採買,烹飪高手蹲地上又炒又煮,飯Q菜香,日子居然過得像是一個家一樣了!只是好景不常,因為洗碗盤的差事總搞不定該輪到誰,就只好遺憾地熄火打烊了。

在那沒有電話手機的年代,所有訊息都靠信件往來,記得入學時每兩人共用一信箱,到我畢業前已變四人共用了。因此,郵局正中的信箱間,是校園聯外也聯內的信息中心,每人每天會報到兩次看信箱。所有海報也都貼在郵局正面,可以讓最多人看見。大四那年,在圖書館與文學院的大菜閒聊,他很苦惱,因為他愛慕一女生,天天寫情書塞到她信箱都被退回,他還給我看他寫的情書,確實讓人不忍卒睹。我們坐著亂聊,想到不如在校園裡寫公開情書,我們說好男的叫東東,女的叫小妮,就在郵局往教堂那條斜徑上,綁上一塊夾板,公開徵求情書。那時有人住教師新村,另批人住坪頂,兩處人就在這裡發表燙人的情話。後來只記得建築系劉胖寫的---「親愛的小妮:我對你的思念,像隻大熊在岩石後面獨自跳舞…」。

住在東海宿舍的日子,真是我們一生中最美好的青春時光,當時全國只有東海提供得起這麼豪華等級的宿舍。 磚牆砌一塊半磚的厚度,外層是不加修飾的清水紅磚,門窗用的是高級台灣檜木,柱樑框架是清水混凝土(最早期用洗石子),內部空間與外部環境設計成為台灣戰後現代建築經典。130多公頃校地供七八百人教學生活,每人平均使用校地1.5公頃以上,有壓不完的馬路、躺不盡的草坪/原,至今仍是世界現代建築十大代表作之一的路思義教堂,就是每天路過、親近、看星星、談夢想的地方,還有文理大道從開闊坡道變成林蔭蔽天,讓師生往來於濃厚人文氛圍的學院之間。

東海人真是得天獨厚,住讀大度山的點點滴滴必然是一生難忘記憶,這片校園永遠牽繫東海人的心。當年這一切是美國教會在歷史機緣下的創舉,培育出一代代格局不凡、心靈出眾的東海人,今日母校決心藉東海人之力,更新男女生宿舍,寄望以前受惠於校園生活的校友挹注資源,讓未來學弟妹們繼續享有優質的校園住讀環境。這應是一個弘大「校策」的開端,要努力邀集校友回饋參與母校的教育大計。

古三國時代,除了有名的孔明向劉備獻隆中策之外,三國魯肅也向孫權獻了榻上策,建議以江東為根本、「竟長江所極,據而有之」,這成為東吳鼎足三分的國策。東海創校一甲子多以來,校友人才濟濟、也如滔滔長河,母校正思「竟校友所極,聚而旺之」,這是固本壯大之道,惟東海人最能體會在心!

---

住讀東海˙福如東海

東海大學校園的整體規劃,由貝聿銘主持,並邀陳其寬與張肇康合作。貝先生是二十世紀偉大建築家之一,1983年獲頒普立茲克獎(相當於建築界的諾貝爾奬),他最有名作品應就是華盛頓國家藝廊東廂(1978)、巴黎羅浮宮增建(1989); 陳、張兩位先生也在後來都成為傑出建築大師。 他們三位合作完成的本校路思義教堂,獲美國蓋提基金會「現代長青計畫」(Keeping It Modern)於2014年選為全球十大最佳現代建築之一,與雪梨歌劇院並列,獲得高額保存調研補助。整個校園的早期建築是台灣戰後的現代建築最佳範例,路思義教堂已登錄為國定古蹟(2019),其他建築物也正陸續被登錄為國家重要文化資產。

榕樹夾蔭的文理大道,兩旁是行政單位與各學院,都呈合院格局與統一屋型,在鐘塔之前的早期建築群的形式表現,就是全校建築設計的基本準則:灰瓦斜屋頂、露明的紅磚牆、水泥柱樑框架(先期以洗石子表面處理、後期為清水混凝土表面)、檜木門窗等,皆為不加修飾的、且高觸感的天然質料。全校屋頂斜率統一為30度(無論是大型的體育館或銘賢堂、或小至郵局與醫護室)、出簷與廊道欄杆、側牆分割、門窗框細部等都一致性處理。因此我們走在校園裡,人總是主角,統一形式的建築成為背景,但這些被統一設計出來的建築,都是世界級的高品質傑出作品。

東海大學於1955年創校時,與當時台灣大學,為全國僅有的兩所大學(清華、交大各於1956、1958年在台復校),其他皆是理工或法商學院。東海創校富有高度理想色彩,採小班制、導師制,並開創圖書館開架管理、勞作制度、師生住校等獨有規定,學生宿舍也不管制燈火,出入圖書館不設限儀容(曾經教官要求圖書館禁止奇裝異服、穿拖鞋的學生進入圖書館,為美籍館長婉拒,他歡迎所有師生前往使用)。

東海學生宿舍同樣保持高度開放自由的住宿空間。 宿舍整體配置受歐洲早期現代主義「新風格」(De Stijl)影響,平面上採取一橫一豎正交組合,彼此互成90度關係,扣接成區,且多是兩兩相接,很少有三棟接在一起。這是全國僅有的宿舍配置組合,是第一個、也是唯一案例。這樣的配置方式,形成又圍封、又開放的似院非院的簇群空間關係,人在宿舍區內、感受到的不是靜止的內部,而是流動、穿透、又富有層次感的內向環境。加上校園位處坡地上,一長棟房子的頭尾兩端有時相差一層樓高度,因為基地一邊高一邊低的緣故,看來好像房子底部從土裡長出來。加上駁坎、階梯、走廊變橋道,這些附加的形式元素,使宿舍區內充滿豐富的空間變化。

如同校園建築形式的統一外觀,各個宿舍屋形及附加元素也皆統一設計,因有大出挑屋簷、連續的開放走廊樓版及欄杆、及駁坎短牆等,共同形成較強烈的水平感,也強化親地性,使得一進入宿舍區,就感覺放鬆、安穩、受庇護。宿舍單邊走廊也是全國宿舍絕少有的,因東海校地大,可以低密度方式興建宿舍,走廊面多朝向西或北,讓房間大窗戶朝南或朝東,避免西曬及冬季北風。單邊走廊的宿舍,一走出房門就迎見戶外景觀,立刻就可與庭院裡的同學打招呼,對採光通風來說也是高度正面的做法,比起一般中央走廊、兩排房間的生活真是天差地別。走廊欄杆採簡單木作,每一柱間以兩條橫桿加短直桿構成,走廊明亮、沒有死角,可供非正式邂逅或停留,尤其對女舍的安全而言,視覺通透而具有高度防衛性功能。

男舍西區(約農河以西),第1-10棟較早完成,柱樑框架為洗石子表面處理, 東區第12-16棟則為清水混凝土柱樑框架,這五棟相傳是張肇康先生負責設計監造,很嚴格要求施工品質。女舍第1-7棟屬早期興建,為洗石子柱樑,第8-10棟據傳是陳其寬先生設計監造的,柱樑採清水混凝土表面處理,建築品質較佳。女生宿舍比男舍的考慮更佳細緻,首先女舍單元設有後陽台,增添很多住宿情趣,也增加房間私密感。早期女舍區內地面層相當開放,男生可以從樓下穿越,可走到女生餐廳用餐,這是因為設計上使用圍牆巧妙地圈出內外空間。

原來的女舍有兩個出入門禁,除了現在的出入管制點外,從郵局前到第7棟前,原有一通道,在7棟前有一圓環,於3、5棟設有管制點,7棟樓下以圍牆圈起,一樓最邊間不設房間,作為通往舊音樂系館的開放路徑。但後來興建新宗教中心,這條路就不通了,圓環取消,內圍牆拆了,以外圍牆圈住全區。現在第1、2、10棟仍以圍牆圈出庭院,第1、2棟之間也留出地面通道。這些原來的圍牆,沿通道側以白漆實牆圍住,另一側就是鏤空磚砌牆,適度保持開放與通風。

男女宿舍都依固定模矩設計,柱樑跨距、門窗開設、走廊寬度、欄杆高度等都以統一尺寸要求,在房間單元安排上,一面開大窗,另一面開高窗,保持通風良好,最特別的是門扇不是正對房間正中央,木門的一邊牆長90公分,可擺下木床的短邊,門的另一邊墻長180公分,正好木床長向可靠牆擺滿,因此可容許以活動傢俱(桌、櫃、床)進行幾乎無限多的各種擺列可能。

宿舍施工方式也是美式規格,譬如一位曾在瑞士工作過的老師提到,東海建築側面外牆與樑版的施作方法,跟他看到的歐洲標準做法是一樣的。宿舍外牆砌一塊半磚厚(一般外牆多為一塊磚厚-約24公分,室內隔牆則是半塊磚厚),具有很好隔熱隔音防潮效果。露明紅磚牆面則按法國式砌法施作,每一列磚皆是一長一短排列,每塊磚必須彼此錯縫(磚縫需彼此錯開),因此砌到轉角時一定得以七五磚收邊(即長度為一般磚長之3/4),砌到最頂層的磚改豎砌且上方切角,這些七五磚、切角磚都必須特別訂做。後期施工的宿舍棟,柱樑框架都是清水混凝土作法,須以上等模板澆灌、拆模後表面不做任何修飾,因此必須事前規劃好表面開口,混凝土品質也必須嚴格控制,尤其灌漿必須充分震動以使砂漿流滿模板內,否則拆模後即現蜂窩(混凝土漿未充分滿實的結果)。門窗皆採台灣檜木製作,室內做窗台板,整體做工很細緻。這些構造上的講究與要求,使得這些建築物的施工造價,比起當時一般行情,要貴出五倍還多。

比起創校初期時大度山一片紅土、植被貧瘠,經過六十多年悉心培育各種花樹,今天的校園已蔚然成廣袤林海,住在森林裡的宿舍,每天在鳥鳴聲中醒來、晚上星月相伴入眠,夏天蟬鳴悠揚,冬日暖陽高照,這大概也是全國唯一如此沈浸在大自然的住宿經驗,也會是一生難忘的讀書交友、浪漫靜好歲月!

最重要的是,好的建築不只是物質性的優越展示,它更是一種精神性的投射期許。東海校園宿舍不只是提供一個床位而已,它以精湛的整體設計品質為同學安頓一種生活在校園的豐盛經驗,將「人」的存在提升到「為己為人」的生命充實之境界,住讀東海,福如東海,養成為東海人,也正是校歌所唱出的「立心立命,立人極於無窮」的大學博雅教育之道。

---漢清講堂 youtube

274 從東海第七宿舍說起 2019-02-25 徐海偉 鍾漢清

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KD4B44VSzJ4

Tapestry: Narcissus

Tapestry

A millefleurs tapestry, Narcissus

Narcissus at the Well

Narcisse se mirant dans la fontaine

French, Paris

about 1500

|

愛德華‧威爾森文集,Half-Earth及Naturalist By "E. O." Wilson 回憶錄《大自然的獵人:博物學家威爾森》。金恆鑣博士:環境生態與文學

141 金恆鑣博士:環境生態與文學 2017-02-18

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFVF_wL5Z_0&t=17s二十年前,讀金恆鑣導讀 E. O." Wilson 回憶錄《大自然的獵人:博物學家威爾森》,"獨具慧眼的田野生物學家",很欣賞金先生的功力。

今天他74歲了,恰巧又在寫Wilson的新著 Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life中譯本的"導讀"。原書首頁無副標題,所以請教他Half-Earth 是什麼意思?他說,這是"地球一半是人(我們)的,另一半是生物(他們)的。"

金恆鑣是(森林)生態學領域之專家、生態學學會理事長。我請教他台灣的森林事情 (相對於日本梅原猛的《森林的哲學》。他說,首先要了解日本的林地多是私有地,所以照顧得很好,反之,台灣的森林都是國有地,公務員不會珍惜的.....

2020.5.11

Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life

http://hcbooks.blogspot.tw/2015/07/naturalist-by-e-o-wilson.html

Object Place: France or Flanders

*****

沒有留言:

張貼留言