昨天梁先生提醒叔本華引言的上下文.

本周四日語老師來電以前都是班長

台灣官方真幸福 喜歡意淫OECD數據.

9/10本月紐約時報:Seamus Heaney, Irish Poet of Soil and Strife, Dies at 74, 1939-2013/ ‘Journey Into the Wideness of Language’

人生真奇怪我昨天在社群網Facebook看到江燦騰先生的留言. 就請教他才發現他竟然是我廠的同事---當年辦公室就在對面---彼此辦公捉可能相距不到十公尺內

江燦騰人的記憶,是脆弱的,要累積思維的厚度,要不停地反覆參考和整合,否則會浪費很多心血

HC江老師 您以前在飛利浦那一單位? 好奇.....

我1979-80在竹北廠TEO 怎麼不認識你?

與江老師通信2封. 與Ken Su談他.

blogging

土石流で列車脱線、12人けが…台湾南部 読売新聞

晚上至8點

與江老師通信2封. 與Ken Su談他.

blogging

土石流で列車脱線、12人けが…台湾南部 読売新聞

台湾交通部(交通省)によると乗客12人が重軽傷を負った。 列車は約250人 ... 日本の対台湾窓口機関・交流協会台北事務所によると、

基隆土石流.....

晚上至8點

The Interpreter (2005)

6.4

Ratings:

6.4/10 from 69,127 users

Metascore: 62/100

Reviews: 403 user | 229 critic | 41 from Metacritic.com

Reviews: 403 user | 229 critic | 41 from Metacritic.com

Political intrigue and deception unfold inside the United Nations, where

a US Secret Service agent is assigned to investigate an interpreter who

overhears an assassination plot.

Director:

Sydney Pollack導演

晚餐票近750萬元/張

Katharine Weymouth, the working-mother publisher,

Hanching Chung (People 人物) - 2 小時前

Katharine Graham《個人歷史 Personal History 》/《華盛頓郵報》新史...

人物她賣掉了四代相傳的《華盛頓郵報》SHERYL GAY STOLBERG 2013年08月31日

[image: 凱瑟琳·韋茅斯,《華盛頓郵報》第四代出版人。]

Matt Roth for The New York Times

凱瑟琳·韋茅斯,《華盛頓郵報》第四代出版人。

-

-

-

-

華盛頓——在華盛頓城一年一度的媒體、政界、好萊塢眾星雲 集的盛典——2012白宮記者晚宴舉辦前夜,凱瑟琳·韋茅斯 (Katharine

Weymouth)也舉辦了她自己的華盛頓名流晚宴。當年,她的外祖母、《華盛頓郵報》先驅出版人凱·格雷厄姆(Katharine

Graham)曾多次舉辦這類晚宴,也因此聞名。

在韋茅斯寬敞通透、精雕細琢的宅邸里,凱·格雷厄姆的摯友 與後人圍坐在晚宴餐桌前,他們中有前總統克林頓的顧問弗農·喬丹(Vernon

Jordan),老布殊在任期間的白宮顧問C·博伊登·格雷(C. Boyden

Gray),凱·格雷厄姆的長子、時任華盛頓郵報公司首席執行官唐納德(Donald),凱的女兒、凱瑟琳·韋茅斯的母親拉里·韋茅斯(Lally

Weymouth),她也是一位踏遍全球的記者、曼哈頓的社交名媛,因採訪數位... 更多 »

印度最寒冷的夏季:經濟危機

Hanching Chung (棄馬保台 亞洲與美國) - 8 小時前

OPINION | Op-Ed Contributor Why India's Economy Is Stumbling By ARVIND

SUBRAMANIAN

India's problems have deep and stubborn origins of the country's own

making.

8月要結束 該整理一下印度最寒冷的夏季:經濟危機

待補

《經濟危機 催化改革》彭博商業周刊 / 中文版

印度總理辛格(Manmohan

Singh)年逾80歲,對他來說,2013年夏天的沮喪是那樣似曾相識。1991年6月,辛格剛擔任印度財政部長,便迎來印度獨立以來最嚴重的經濟危機。該國外匯儲備驟減,僅相當於數周進口額,黃金儲備也被空運到倫敦,作為獲取國際貨幣基金組織(IMF)貸款的抵押品。

不論是全民樂觀情緒,還是辛格的良好聲譽,目前都面臨空前考驗。印度經濟增長率已跌至十年低點,儘管央行加息令投資受到抑制,通脤率仍居高不下。國家財政赤字與經常帳赤字也告危。近幾周,印度盧比崩跌,自年初以來,兌美元貶值超17%,是今年亞洲表現最差的貨幣。

外界普遍認為印度正面臨1991年以來最嚴重的危機。不過,雖然目前形勢看似一片慘淡,未來的印度也大有可能擺脫困境並變得更強大。事實上,我們可以說,眼下的掙扎或許正是印度振興經濟所需的... 更多 »

The adidas method

Hanching Chung (新經濟學與台灣戴明圈: The New Economics and A Taiwanese Deming Circle) - 9 小時前

愛迪達成功之道:看穿顧客在想什麼http://www.cw.com.tw/article/article.action?id=5051794

2013-08-30 Web only 作者:經濟學人

[image: 愛迪達成功之道:看穿顧客在想什麼] 圖片來源:陳德信10年前,運動服飾製造商不停地為產品增加功能和未來主義設計,它們相信,消費者會依照技術規格來購買訓練鞋。但是,愛迪達

(adidas)現任運動服飾創意總監卡恩斯(James Carnes),在2004年奧斯陸會議中碰上了丹麥的顧問拉斯繆森(Mikkel

Rasmussen);拉斯繆森挑戰了這個看法,他說,一支手機可能有72個功能,但那比大部分人想要、或是會用的功能多了50個。

那讓卡恩斯非常好奇,也讓他決定與拉斯繆森的小顧問公司ReD展開長達10年的合作。在那10年之中,愛迪達的銷售和股價皆穩定成

長。全球龍頭耐吉(Nike)的行銷是以運動明星代言為主;彪馬(Puma)的行銷佔營收比例更高,並跨足非運動休閒服飾領域,銷售亦有所成長,但仍遠遠

落後主要對手耐吉和愛迪達。愛迪達的行銷較為低調,預算佔營收比例也比前兩間公司低,雖有三分之一的銷售出自「生活類」產品,不過運動服飾仍舊是愛迪達的

核心業務。

愛迪達必須從基本面著手,才能在這個毛利微薄的領域中成功,例如,愛迪達得遵循競爭對手的做法,將生產外包以... 更多 »

BBC的Design Icons 系列文章:Pompidou Centre: A radical with enduring appeal

At the head of the table sat Ms. Weymouth, a

Harvard- and Stanford-educated lawyer, single mother of three and, at

47, a fourth-generation publisher of The Post. As her guests chatted,

she gently intervened, steering the conversation, salon-style, toward

the economy and presidential politics. When it was over, Mrs. Weymouth,

not an easy one to please, showered her daughter with praise.

“It was a big moment,” said

Molly Elkin, Ms. Weymouth’s best friend and one of the dinner party

guests. “It was sort of like: ‘I’ve passed the baton, kid. You’ve

learned well, you did a good job.’ ”

It was the kind of scene,

rife with unspoken family drama, that captivates longtime

Washingtonians, who have scrutinized and mythologized the Grahams for

decades, much as the British do their royalty. Now, in an exceedingly

difficult climate for newspapers, Ms. Weymouth is charged with saving

the crown jewels. In a city and a clan filled with expectations for her,

that is no easy task.

She is carving her path in a

capital, and an industry, vastly changed from the one her grandmother

inhabited when big-city newspapers were flush with advertising; The Post

helped bring down a president; and for nearly four decades, Mrs. Graham

ruled social Washington, feting presidents and prime ministers in her

elegant Georgetown manse, dining at the White House with kings and

queens.

“There is never going to be

another Kay, never in Washington, because the times are different,”

said Sally Quinn, the columnist and the wife of Ben Bradlee, the editor

whose partnership with Mrs. Graham was chronicled in “All The

President’s Men.” “People just don’t entertain that way,” Ms. Quinn

said. “People have kids, they work late. That is not what Katharine

wants to do.”

Ms. Weymouth is many

things: a working mother and enthusiastic cook; a fearless skier (“She

has not met a slope she won’t take,” says Liz Spayd, a former managing

editor of The Post); a fitness buff (“She can crunch till the cows come

home,” said Pari Bradlee, a yoga instructor and daughter-in-law to Ben)

and, for a while, one of the most sought-after dates in town. (After

seeing a local architect, Ms. Weymouth has recently reunited with an old

flame, Marty Moe, a former AOL executive.)

She does not take her

famous name too seriously, and she likes to have fun. For years, she and

Ms. Elkin, a labor lawyer, held a backyard Summer White Party, a spoof

on the lavish Black and White Ball hosted in 1966 by Truman Capote to

honor Mrs. Graham. Once, at a club in Aspen, Colo., Ms. Weymouth spied

Yankees third baseman Alex Rodriguez watching her dance.

“We are the only people in

this club who don’t want anything from you,” she announced. “Come dance

with us.” He said he would rather watch.

To her 2012 “grown-up”

dinner, she wore a $35 scoop-neck sleeveless sundress from J. C. Penney,

a playful nod to an important Post advertiser whose chief executive at

the time, Ron Johnson, was a guest. (She bought J. C. Penney dresses for

Ms. Elkin, who wore hers, and Mrs. Weymouth, who wouldn’t be caught

dead in one.)

Ms. Weymouth’s penchant for

showing off her athletic figure — she arrived for a photo shoot in a

crisp white sleeveless sheath and four-inch lime green Jimmy Choos —

provokes titters in the newsroom. Then again, she works hard for it; Ms.

Elkin said the two spend Sunday mornings doing free weights and “boy

push-ups” with a personal trainer.

“We smack-talk each other the entire time,” Ms. Elkin said, “just like we did when we were 20 years old.”

Quick-witted and

no-nonsense, Ms. Weymouth is more like her steely grandmother than her

famously demanding and mercurial mother. But since becoming publisher in

February 2008, she has had a rocky ride; she has already hired her

second editor, and critics lament that she is presiding over a newspaper

in retreat.

Ad revenue is declining and

average daily circulation was 474,767 in March, down from 673,180 when

Ms. Weymouth took over, the Alliance for Audited Media said.

Lacking the magic bullet,

she is emphasizing a local mission — she has reduced staff, shut bureaus

in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago and eliminated the well-regarded

Book World section on Sunday — to meet demands by her uncle, and The

Post board, that the newspaper turn a profit. (It is, she said,

although on Friday the parent company reported a 14 percent drop in second-quarter earnings, compared to a year ago.)

Recently, she upset

sentimentalists by putting The Post’s 15th Street headquarters up for

sale. She says her grandmother always hated the boxy building.

But while Mrs. Graham, who

took over the company in 1963 after her husband’s suicide (and later

became publisher and chief executive), battled lifelong insecurities as

she transformed herself from a 1950s housewife to the first woman to run

a Fortune 500 company (as well as the author of a Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir), not so Ms. Weymouth.

“Katharine is far more

comfortable in her own skin than Kay ever was,” said Robert G. Kaiser, a

Post associate editor who has worked there for 50 years. Still, he

said: “She has a burden. Your biggest anxiety, as I know from personal

experience with Kay and Don, is: ‘Am I going to screw this up? Am I the

one who is going to be remembered as the goof-off who couldn’t keep it

together?’ ”

On a steamy summer Friday

in July, Ms. Weymouth was curled up on her living room couch, not in

fashionable Georgetown but in the practically suburban northwest

Washington neighborhood of Chevy Chase, where a Post honor box and fleet

of scooters are parked on her front porch. Her golden retriever,

Dakota, scampered about, a slobbery tennis ball in its mouth.

If her social life is

centered anywhere, it is here, in the house she shares with her children

Madeleine, 13, Beckett, 11, and Bridget, 9; an assemblage of pets

(three dogs, a guinea pig, a rabbit, two gerbils and a hamster); and a

grandmotherly housekeeper, Olinda, whom she “sort of inherited” from

Mrs. Graham. It is the scene of countless family dinners with her tight

circle of friends, including Ms. Elkin, whom she met at Oxford.

Ms. Weymouth is proud of

her culinary skills, another break from family tradition. “My mother

doesn’t cook, my grandmother didn’t cook,” she said. “Her kids were

raised by servants. They would joke about Sunday night dinner. It was

the only night she would cook, and apparently it was just horrendous,

like scrambled eggs and Campbell’s soup.”

On this afternoon, she had

left work early to prepare yellow gazpacho, swordfish kebabs with bacon

and cherry tomatoes, and strawberry shortcake for 10 friends and

colleagues, including the Post foreign editor, who had returned from

Afghanistan. Her daughter Bridget wandered in nibbling a piece of bacon.

Ms. Weymouth frowned (“I

need that for dinner!” she said), but it was a mock frown, a precious

moment of normalcy. In April 2011, when Bridget was just shy of her

seventh birthday, she fell off a pony, mangling her left arm. She spent

28 days undergoing a dozen operations at Children’s Hospital here (and

later two more in New York). Ms. Weymouth moved in, conducting business

meetings from the child’s bedside.

“She was dealing with

doctors and surgeons and a child who was in a lot of pain,” said Kevin

Sullivan, a Post reporter and close friend. “But it wasn’t like she

flushed her BlackBerry down the toilet. It’s not one of those jobs where

you can say, ‘I’ll be gone a couple of weeks.’ ”

Moving to Washington to

join the family business, Ms. Weymouth said, was never in her “grand

plan.” Dowdy D.C. seems a world away from her childhood in Manhattan,

where she attended the all-girls Brearley School and danced the

“Nutcracker” while studying, quite seriously, with the School of

American Ballet.

Her father, Yann Weymouth, a

noted architect (and brother of bassist Tina Weymouth, a founder of the

Talking Heads) and mother divorced when Ms. Weymouth and her younger

sister Pamela were little. The girls were raised in their mother’s orbit

on the Upper East Side, in the swirl of New York’s literary circles.

It was a childhood spent

going out to restaurants (“Grandma disapproved,” Ms. Weymouth said) and

drinking Cokes at Elaine’s. They tagged along on Lally’s reporting trips

— “We got to have dinner at the Club d’Alep and meet some of the Syrian

aristocracy” — discussed fashion with the Vogue editor Diana Vreeland

and politics with Alexander Cockburn, the left-wing British journalist

and, for a time, Mrs. Weymouth’s live-in boyfriend.

“It was rarefied,” said

Diane Paulus, the Broadway director (“Hair,” “Pippin”), a close friend

since the third grade. “We were like 8- or 9- or 10-years-old, and there

were big grown-up dinner parties and each child would give toasts.

Lally was very social, very fashionable, very chic and very vocal in her

politics. There were always political discussions, and she expected the

children to keep up.”

But at Harvard, and later

Oxford, where the future publisher briefly pursued a master’s degree in

literature — “My mother told me I had to go to graduate school,” Ms.

Weymouth explained — and Stanford Law, she rarely let on who she was.

At Oxford, she drank beer,

rowed crew and went through a black leather phase — “She scared me, she

was so cool,” Ms. Elkin said — which turned almost comical on a trip to

Israel. During a stopover in Paris to see Mr. Weymouth, who was helping

I. M. Pei design the glass pyramid at the Louvre, Ms. Weymouth produced a

lengthy itinerary, drafted by her mother, including lunch at the

Knesset with Benjamin Netanyahu and dinner at the apartment of Yitzhak

and Leah Rabin.

“So the security people are

looking at her, with her black eyeliner and her leather jacket and

these black earrings, and they’re like, ‘Who are you?’ ” Ms. Elkin said.

“And I’m looking at her and saying: ‘Yeah, who are you? And why did you

only tell me to bring one dress?’ ”

Ms. Weymouth loved the West

Coast and hoped to stay there after law school. Her mother had other

ideas. “I thought it was a nice place for a weekend,” Mrs. Weymouth said

in an interview, “not for a life.”

Instead, she took a job as a

litigator with Williams & Connolly, The Post’s law firm. Nicole

Chapman, her Harvard roommate, said she wanted to “establish herself as

Katharine Weymouth,” and eventually have children, becoming a “more

there mother” than her own had been.

To herald the arrival of

her oldest grandchild, Mrs. Graham invited Washington’s young

up-and-comers to a dinner party. George Stephanopoulos, then with the

Clinton administration, was there. Mr. Jordan sent his niece, Carolyn

Niles, now a close Weymouth friend. “She really took the time to

establish social connections for Katharine,” Ms. Niles said.

If Kay Graham saw her

namesake as her heir apparent, she did not say, though it was apparent

they were extremely close. Ann Calfas, a Stanford classmate of Ms.

Weymouth, recalls the grandmother’s simple delight in driving them to

the wedding of a friend. “She was like, ‘Girls, hop in!’ ”

Ms. Weymouth has her own

fond memories of Friday night “dates” when Mrs. Graham needed a party

escort, and of quiet dinners in the library of the big house on R Street

in Georgetown. “We would eat on the TV trays and gossip,” she said,

“and I would tell her about my love life and she’d crack up.”

In 1996, The Post put out a

call to Williams & Connolly for temporary legal help. Ms. Weymouth

put her hand up, and the job became permanent, leading to stints in the

online operation (then a distinct subsidiary) and ultimately as vice

president for advertising.

Inside the newsroom, one

rap on Ms. Weymouth is that unlike her uncle, she has never been a

reporter. Over the years, she said, they talked about it, but she didn’t

feel qualified. “I just felt like it would be too weird,” she said.

If there is one decision

Ms. Weymouth has made that has mystified people who know her well, it

was her July 1998 marriage to Richard Scully, a Washington lawyer. The

wedding at her mother’s Southampton home, with 470 A-list guests, was a

typical Lally extravaganza. Not only did Oscar de la Renta design the

dress, a friend said, he was there to zip it up.

The divorce in 2005 was

messy. Court records show they fought over their $70,000 country club

membership (Mr. Scully, a golfer, testified that Ms. Weymouth “doesn’t

really value it”) and their German shepherd, Maxine, among other things.

The court awarded both to Ms. Weymouth.

Last year, Mr. Scully was

accused of assaulting his girlfriend. The charges were dropped, but Ms.

Weymouth went back to court, asserting that he had stalked her through

texts and e-mail and engaged in “angry and explosive outbursts” in front

of their children. Mr. Scully’s lawyer, Mark E. Schamel, called the

allegations “false” and attributed Ms. Weymouth’s assertions to an

“opportunistic pleading” filed by her divorce lawyer.

Ms. Weymouth and her tight-knit circle prefer not to discuss it. “The less you say about him, the better,” Lally Weymouth said.

Friends say Ms. Weymouth

has become the ultimate hands-on mother (albeit one with

“one-and-a-half” nannies, as she describes it), waking up early to make

the children a hot breakfast and driving them to school every morning.

In a city of nightly parties, she picks and chooses. She is a regular at

galas for the Alvin Ailey dance company and the PEN/Faulkner

Foundation, because Ms. Elkin is on the board.

But at this year’s White

House Correspondents’ Dinner, Ms. Weymouth was nowhere to be seen. She

was home hosting a sleepover; it was Bridget’s ninth birthday.

Not long after her

grandmother died in 2001, Ms. Weymouth had a dream. In it, they strolled

the beach on Martha’s Vineyard, where Mrs. Graham owned a home.

“In my dream, I knew she was dead,” Ms. Weymouth said. “But she said: ‘I’m sorry. I’m sorry I have to leave you.’ ”

Ms. Weymouth sees no larger

meaning in this — “I don’t believe in hoo-ha,” she said — though as she

charts the future of her family’s business, she is also immersed in the

past. Pictures of her grandmother line the walls of her office, where

Mrs. Graham’s memoir, tagged with sticky notes for Ms. Weymouth’s

speeches, is on a shelf. For her first day on the job in February 2008,

she wore Mrs. Graham’s pearls “for good luck.”

Her ascension generated the

predictable buzz in Washington. People speculated about whether there

was competition between Ms. Weymouth and her mother, who, the theory

goes, remains miffed that her kid brother inherited the throne. (Not

true, both women say.)

Ms. Weymouth took the helm

just as the bottom was about to fall out of the economy. The newspaper

had already gone through several newsroom buyouts, and she told her

uncle she would not take the job unless she could integrate the digital

and print operations. “Don was hellbent against it, and probably still

is,” she said.

Deciding a new editor was

needed, she picked Marcus Brauchli, from The Wall Street Journal, the

first outsider to edit The Post in four decades. Magazines gushed that

she had found her Ben Bradlee, but the relationship soured after news

broke that they planned to offer lobbyists the chance to underwrite

“intimate and exclusive” dinners, for up to $250,000, with Obama

officials and Post journalists in Ms. Weymouth’s home, a seemingly crass

version of Kay Graham’s salons.

Ms. Weymouth apologized, but the negative publicity over “Salon-Gate” was brutal. Ms. Niles said it was the first time she had seen her ordinarily unflappable friend cry over work.

Within the Graham family,

there is great sensitivity to any suggestion of nepotism. Don Graham,

68, praises his niece as “passionate, hardworking, utterly decent” and

also qualified. As to whether she will inherit his job, he ducks the

question: “I’m not expecting her to go anyplace.”

One hint, Post tea-leaf

readers say, can be found in the company garage. For years Kay Graham

drove a car with the low-numbered District license plate No. 149, which

once belonged to her father, Eugene Meyer, who bought The Post at a

bankruptcy sale in 1933. Now it is on Ms. Weymouth’s 1991 BMW

convertible.

In the meantime, things have been looking up. In January, Ms. Weymouth replaced Mr. Brauchli with Martin Baron,

a no-nonsense newsman from The Boston Globe (and, previously, The New

York Times), who has won praise for sharpening coverage and boosting

morale. Reporters at The Post who routinely question whether their

publisher “gets what we do,” now wonder if maybe, just maybe, she has

found her Ben Bradlee after all.

“She made a brilliant choice,” Ms. Quinn said, “and it’s working.”

Not everyone is so

effusive. The Post recently began charging for online access, but the

climate for newspapers in general, and The Post in particular, remains

tough. Mr. Baron called Ms. Weymouth “a realist,” who “still wants us to

do really great journalism,” albeit “within the reality of our economic

circumstances.” But he could not rule out further cuts.

The question, inside and

outside the newspaper, is whether Ms. Weymouth can ever be the great and

beloved publisher her grandmother was. “Certainly the genes are there,”

said John Morton, a newspaper industry analyst. “It’s the judgment that

has yet to be proved.”

Others seem to have written her off. The Guardian columnist Michael Wolff recently criticized Ms. Weymouth, declaring her “a disaster in a job for which she had, other than her lineage, no qualifications.”

Ms. Weymouth, mindful of

her past yet unsentimental about it, seems unconcerned. Her mother

“tells me she is proud of me,” she said, and “if I’m not doing a good

job, as much as Don loves me, he will fire me.” Even her grandmother,

she said, grew into greatness, making mistakes along the way.

“I don’t feel like my job

is to be beloved,” said Ms. Weymouth, the woman who might be known as

the working-mother publisher, with her children at play and her dogs at

her feet. “I certainly hope to be a great publisher, and if people want

to love me, too, that’s even better.”

你在的時候,我都上早班,晚上去臺北讀夜大。

HC真不可思議竹北廠有你這種高人而我不知道.洪 (鐵城

財務)經理經常過來嘲笑我們"這一代"......"天下文化出版你的"傳記"我也忘記買.現在應該買不到了. 一定比羅(益強 總裁)先生的還好玩

江燦騰 羅先生認識我,也替我的傳記寫推薦。

http://hcpeople.blogspot.tw/2013/07/blog-post.html

給他mail.

Pompidou Centre: A radical with enduring appeal

HIDE CAPTION

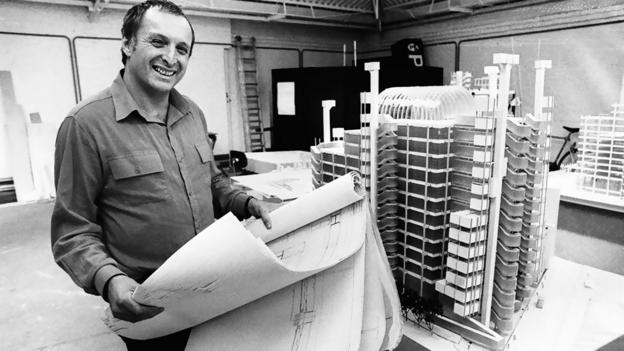

- Competition time

- In 1969, Richard Rogers, a young British architect, was persuaded to enter a competition to design the Pompidou Centre by his friends Renzo Piano and Ted Happold. (Photo: Corbis)

The Pompidou Centre was panned by the critics when it opened in 1977.

But its colourful exuberance has ensured its lasting popular appeal,

writes Jonathan Glancey.

“The

funny thing looking back is that, to begin with, I hadn’t been at all

keen on the project”, says Richard Rogers of the Parisian building that

made him world famous. The Pompidou Centre – a still shocking, if much

admired hi-tech cultural centre in the heart of Paris – was, at the time

an international competition was held for its design in 1969, a symbol

of everything the 36-year-old left-wing architect stood against.

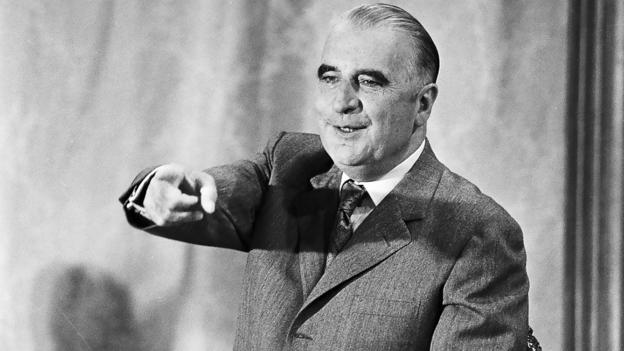

What was known then as the Centre Beaubourg was to be a state monument, a centralised museum proposed by a new, right-wing French president, Georges Pompidou, the very man who, as prime minister under President de Gaulle, had put a end to the student demonstrations and riots of the previous year. Many in France believed these to be the opening shots in a new French Revolution that would bring down General de Gaulle, his government and the state itself, together with proposals for costly national monuments.

After much intellectual arm-wrestling, Rogers was persuaded by colleagues and associates – principally Ted Happold, a structural engineer, and Renzo Piano, a lively Genoese architect raised in a family of builders – to have a shot at the Parisian competition.

Even then, the team of young long-haired, tie-dyed architects and engineers nearly missed the last post with their package of drawings, one of 681 entries in the competition. A month later, Rogers’ phone rang. It was Piano. “Vecchio” he said, (Piano has always called Rogers, who is four years older, “old man”), “are you sitting down? We’ve won the Pompidou . . .”

It was hard to believe. The Piano and Rogers’ design looked like no other museum or cultural centre. With exposed and brightly coloured ductwork and escalators climbing, zigzag style in transparent tubes across its challenging façade, the building was planned as “a cross between the British Museum and Times Square.” It was as hip a design for a public building as could be imagined, a cultural centre for the iconoclastic new worlds of Pierre Boulez in music, Andy Warhol in art and Jean-Luc Godard on screen.

Are friends electric?

The first sight of the design team did little to sway establishment fears in France that they had been landed with the architectural equivalent of Electric Ladyland by the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

“Renzo says we were the ‘bad boys’ of architecture”, says Rogers. “When President Pompidou looked at the drawings, all he said was “Ça va faire crier” [This is going to make a noise]; but, we moved to Paris for five years, it got built on time and within budget, and it was a big success.”

President Pompidou had been remarkably gracious to these young radicals. As for popularity, the cultural centre that now bears his name entertained six million visitors in its first year – making it more popular than the Eiffel Tower.

Because it was so avant-garde a design, it was a challenge to build, especially so when the budget was cut in half. Rogers and Piano relied heavily on the ingenuity of Peter Rice, a brilliant young Irish structural engineer, who had only recently solved the problem of how to build the wild, sail-like roofs of the Sydney Opera House.

Beam me up

“Peter transformed the competition entry for Pompidou from a design that was in some ways too mechanistic into one that was humanistic”, says Rogers. “He softened the whole look of the building through the way he reconfigured the structure. There’s a lot of handcraft in the building, too, which might surprise a lot of people, and that’s one of Peter’s great contributions. The cast steel ‘gerberettes’ – or special beams – that allowed us to have a deep, free floor space by carrying the weight of the floors to the outside of the building brought light and grace to the final structure; they were fettled by hand.”

Rice was thrilled when he came across an old Parisian lady stroking the cast steel beams of the building – telling him how lovely the texture was. “Before working with Peter, we existed in a world of I-beams and the kind of conventional steelwork that would have made the walls of Pompidou look heavy; we were looking for transparency, the idea of a cultural centre that was truly open to everyone with nothing to hide from the public” he said

The Pompidou Centre opened in 1977. By and large, critics panned it. It was an “oil refinery” of a building, shocking, provocative and insensitive to the city streets around it. And, yet, it has become one of the key buildings of the second half of the 20thCentury, and hugely popular for its location, events and the enduring appeal of its extrovert and adaptable design, a colourful climbing-frame of a building extending an open invitation to all ages and generations.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

What was known then as the Centre Beaubourg was to be a state monument, a centralised museum proposed by a new, right-wing French president, Georges Pompidou, the very man who, as prime minister under President de Gaulle, had put a end to the student demonstrations and riots of the previous year. Many in France believed these to be the opening shots in a new French Revolution that would bring down General de Gaulle, his government and the state itself, together with proposals for costly national monuments.

After much intellectual arm-wrestling, Rogers was persuaded by colleagues and associates – principally Ted Happold, a structural engineer, and Renzo Piano, a lively Genoese architect raised in a family of builders – to have a shot at the Parisian competition.

Even then, the team of young long-haired, tie-dyed architects and engineers nearly missed the last post with their package of drawings, one of 681 entries in the competition. A month later, Rogers’ phone rang. It was Piano. “Vecchio” he said, (Piano has always called Rogers, who is four years older, “old man”), “are you sitting down? We’ve won the Pompidou . . .”

It was hard to believe. The Piano and Rogers’ design looked like no other museum or cultural centre. With exposed and brightly coloured ductwork and escalators climbing, zigzag style in transparent tubes across its challenging façade, the building was planned as “a cross between the British Museum and Times Square.” It was as hip a design for a public building as could be imagined, a cultural centre for the iconoclastic new worlds of Pierre Boulez in music, Andy Warhol in art and Jean-Luc Godard on screen.

Are friends electric?

The first sight of the design team did little to sway establishment fears in France that they had been landed with the architectural equivalent of Electric Ladyland by the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

“Renzo says we were the ‘bad boys’ of architecture”, says Rogers. “When President Pompidou looked at the drawings, all he said was “Ça va faire crier” [This is going to make a noise]; but, we moved to Paris for five years, it got built on time and within budget, and it was a big success.”

President Pompidou had been remarkably gracious to these young radicals. As for popularity, the cultural centre that now bears his name entertained six million visitors in its first year – making it more popular than the Eiffel Tower.

Because it was so avant-garde a design, it was a challenge to build, especially so when the budget was cut in half. Rogers and Piano relied heavily on the ingenuity of Peter Rice, a brilliant young Irish structural engineer, who had only recently solved the problem of how to build the wild, sail-like roofs of the Sydney Opera House.

Beam me up

“Peter transformed the competition entry for Pompidou from a design that was in some ways too mechanistic into one that was humanistic”, says Rogers. “He softened the whole look of the building through the way he reconfigured the structure. There’s a lot of handcraft in the building, too, which might surprise a lot of people, and that’s one of Peter’s great contributions. The cast steel ‘gerberettes’ – or special beams – that allowed us to have a deep, free floor space by carrying the weight of the floors to the outside of the building brought light and grace to the final structure; they were fettled by hand.”

Rice was thrilled when he came across an old Parisian lady stroking the cast steel beams of the building – telling him how lovely the texture was. “Before working with Peter, we existed in a world of I-beams and the kind of conventional steelwork that would have made the walls of Pompidou look heavy; we were looking for transparency, the idea of a cultural centre that was truly open to everyone with nothing to hide from the public” he said

The Pompidou Centre opened in 1977. By and large, critics panned it. It was an “oil refinery” of a building, shocking, provocative and insensitive to the city streets around it. And, yet, it has become one of the key buildings of the second half of the 20thCentury, and hugely popular for its location, events and the enduring appeal of its extrovert and adaptable design, a colourful climbing-frame of a building extending an open invitation to all ages and generations.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

沒有留言:

張貼留言