84) 最難忘是友情(:1974年12月29:故友彭淮棟、蔡英文。匡漢、林世堂、阿熙 ) ;2013年補《康德書信》一段;2022年補 "重讀 (可接下講半本) 陳之藩《劍橋倒影》)1972)":李約瑟"問題"; 他訪問東海.....;一種Cavendish Laboratory 史

https://www.facebook.com/hanching.chung/videos/828415938136583

“平生鑽故紙,夙好老尤篤。”

清楚地認識到自己的能力以及運用這種能力的界限,將會使人們在一切良好的、有用的東西面前變得確信、勇敢而堅定。相反,不斷地用甜美的希望欺騙人們,用不斷更新的、但卻時常失敗的嘗試,把人們羈絆在超出自己的力量的事物之中,將會導致輕視理性,、進而導致懶惰或者狂熱幻想。---李秋零編譯《康德書信百封‧致約翰‧貝林 (1786.4.7)》上海人民出版社,1992,頁103-104 "2013

"重讀陳之藩《劍橋倒影》)1972)"

劍河倒影 序──如夢的兩年

......

最初的一兩個月,都是在看閒書,聊閒天中過去的。因為看到好多事都很新鮮,於是就一連寫了十篇「劍河倒影」寄給《中央日報》。嗣即接到好多朋友的信,其中有梁實秋先生的謬獎;林語堂先生的申論,還有好多朋友說:太好了,你又提筆寫散文了。

但是十篇寫完以後,我就覺得不太明白劍橋,有「出口便錯」的危險。於是多看些再說,可是越看得多,越不敢寫。雖然我那時整天看閒書,聊閒天,並沒有看我本行的東西,也並沒有寫出散文來。

劍橋之所以為劍橋,就在各人想各人的,各人幹各人的,從無一人過問你的事。找你愛找的朋友,聊你愛聊的天。看看水,看看雲,任何事不做也無所謂。在一九七○的前半年,我幾乎沒有看一本本行的書。好像壞學生放了假時的狀態。這時候,台北卻出現了《劍河倒影》的集子,除了那十篇散文外,還找出我未出國以前的幾篇文章,可能是那位店東的剪貼簿罷,大登廣告,出版了。不經同意替我出書,倒在其次;使人看來很不舒服的,是還寫了一段很輕浮的廣告,書裏面又是數不清的錯字別字。使我對那種無法無天的作風難過了好幾天。

於是,為辨正計,我又繼續寫了三篇,表示倒影尚未寫完,該集顯係盜印。這場無從打起的仗,使我苦惱了一陣,我又忙著在劍橋、在曼徹斯特、在倫敦講演去了。

一講演,就有提問題者,一提問題,就刺激出興趣來。我在曼徹斯特有一次講完,麥克法蘭教授提一問題,使我大感興趣。於是回到劍橋,又弄起本行來。等我第二次在劍橋報告時,克路司教授讓我把這個有趣的結果寫出來。我大概用了三四個月的時間,寫成了一本小書似的。

內容是有些創造性;我也是有兩三夜興奮得睡不著。但我們對創作性的東西,並不像劍橋的人那麼看重。只要是創見,他們就覺得好得不得了。可是如為繼續引申的東西,他們就覺得那不是劍橋應該做的。

所以,克路司教授比我還興奮。他把麥克法蘭教授找來,兩個人考起我來。一小時後,他說:我推薦你的論文到學位會去,作為哲學博士論文。如此,快到兩年的時候,完成了劍橋的哲學博士。

等到禮服店把我那套服裝送來,我確實很喜歡;因為那頂帽子,並不是尋常的樣子,是黑絨做的橫圈式加上金色的繩子。那個形狀,在莎士比亞的戲中是常見的。原來想寫二十篇的「劍河倒影」,因為這個博士學位給攪亂了。又寫了一篇之後,就是離開劍橋的時候了。二十篇的預想始終交不了卷,也只好算了。

此時,台中又出了新的盜印本,包括我那三篇一九七○年作的,印得更壞,錯字更多,到了一種不能看的地步。

這麼幾篇稿子,本沒有成集的可能,但在兩次盜印之後,文字已被誤植得不成體統;我還是負責把它印出來,以對得起對我的散文有偏好的讀者。

在劍橋的好幾個學院的晚會中,與人談起,常常有人誤認為我是學文學的,不然,為什麼知道那麼多文學上的故事?

比如,談起哈代來,我說哈代應算是劍橋的,因為他有個朋友在王家學院,哈代受這位朋友影響最深。

比如,談起莎士比亞來,我立時說出《溫莎的風流婦人》是在一個禮拜中趕成的。比如,談起艾略特來,我說離劍橋不遠的那個小教堂就在他的一首詩裏。

有時,我自己也奇怪,這些知識都是什麼地方來的呢?沒有來美國前,在台北的五年中,我很幸運的作了梁實秋先生的鄰居,每天晚上都到他家談天,五年的時間,他談的太多了,我聽的也太多了。而這種聊天,我到劍橋後忽有一天悟出,不正是不折不扣的劍橋精神嗎?

確實是我的幸運,在台北與實秋先生談了五年天,在劍橋又與成百的學者談了兩年天。每天有解惑後的清明與聞道中的喜悅。所以,我願不顧寒傖的把這本小書獻給他們,尤其是實秋先生。

內容簡介

國家科學基金會每年從美國全國大學中選近百位教授到歐洲幾個著名大學去訪問。一九六九年,我很幸運的獲選。於是接洽劍橋大學。我給克路司教授寫了封信,他很快的回信說:他們每年在控制部門只接受一位;而該年度已選妥加里佛尼亞伯克來的一位教授作為訪問者。不過呢,在信上他又加上一句,你如果能來此作為學生,誰也阻攔不了你。 我當時覺得劍橋已沒有了希望,於是改治倫敦大學。然後向一位曾留英在美執教的朋友商量。他說:「去倫敦大學作什麼呢?與美國的大學一模一樣。還是設法去劍橋。當這兩個老大學的學生是件很光榮的事。你查查多少名人的傳記,他們曾經要去牛津或劍橋去當Fel-low,也就是研究生。」一九七二年一月十五日於休士頓大學

本文摘錄自《劍河倒影》

|

他的散文富有哲理與詩情,尤其『劍河倒影』裡十三篇文章,各有其獨立的主題,不同的角度,不同的技巧,展現出作者不同的感受、那份純真樸實的感情,每篇文章都蘊含著深湛的哲理,令人回味、拍案叫絕。

第一篇是:

實用呢,還是好奇呢?

從休士頓中午上飛機,吃兩次飯,睡一次覺,就是倫敦了。因為我從來不預先準備甚麼,更談不到預定旅館。在倫敦轉了一兩個鐘頭,我知道不可能找到房間,於是就搭上劍橋的火車。車廂裡只有兩人,我問他:「去劍橋在那一站下車?」他說,當然是最後那一站。

車廂破爛的程度,我想就是我在廿年前從西安去寶雞的火車可以相比。美國有的火車很糟,台灣有的支線上的火車很爛,都比這列火車要強多了。可是,它卻有一個特色:那即是爛而不髒。無論多窮多破而不髒,是一種特有的文化。這種文化也許舉個例才能說明。我小孩時在北平的鄰居是家旗人,每天以典當為生,家貧到了如此的地步,可是不髒,每天擦呀、洗呀,弄得一塵不染。我想所謂清貧是如此之謂罷。

於是,這一列清貧的火車穿過山洞,經過綠野,在一片秋光裡慢慢停下來,可不是嗎?這是劍橋。

好在這是終點,不然我可急壞了。我怎麼也開不了開門,因為並無把手可開。後面那位唯一的同伴走過來,很熟練的把手伸到沒有玻璃的門窗之外,一下就開了。這樣爛的車,這種開門法,也是理所當然的事。

這個站,除了是露天外,不比新竹車站大,而出口又有收票處,與新竹站更像了。我好像覺得我又在走出新竹車站,到清華去教書似的。自己提醒好幾次:「這是劍橋,這是出牛頓,出法拉第,出馬克士威爾,出惠斯登的地方」。我這一行,一下就想出這麼多大師均出自劍橋,世間三百六十行,再乘以三百六十,你看這兒出過多少大師罷。搖搖頭,不大相信。

過了些小街小巷,安頓在一個旅館裡。

在飛機上吃足了,並不餓;也睡足了,並不睏。反正在這兒的日子最少也要一年呢,也不急於東看西看的。沿著小街,信步走去。眼睛忽然一亮,再仔細一看,不自主的笑起來。

難怪小赫胥黎到了美國說:「怎麼美國連一本書也沒有呢!」。我來到一個小書舖的前面。

在美國找到一間書店是件很不容易的事情,找到一間有點正式的書的書店,更難。而我信步所至,在這個小街,這麼個小店,發現這麼多可愛的書,眼前好像有一片眩目的光芒。掏出一把在倫敦飛機場換來,還不會使用的錢,讓店東挑了兩先令去,帶回一本『新科學家』來。

三翻兩翻,即看到很熟悉的幾張畫。仔細一瞧,這些畫全是中國的東西,一張是一零六一年湖北的鐵路;一是一六二一年射火箭的車;一是一六一零年河北的拱橋,最好玩的是一張木刻,是用河水推磨,用磨拉風箱,用風箱吹起旺火。

細看一下,原來是尼丹約瑟新出的一本書的書評。這本書叫做『東西方的科學與社會』,大概是他從一九三七到一九四六的論集。主要的內容是中西科學的比較,中國科學對西方的影響,中國社會與中國科學的關係等等。他發現了許多發明出自中國。並有照像或圖畫作為證明。

很自然而然的,我們會問:為甚麼那麼多發明,即沒有導出像歐洲近五百年的科學發展?尼丹約瑟,畫龍點睛的結論是:中國科學在整個發展過程中主要是為了「實用」。

這位寫書評的「牛津」教授反問說:歐洲近五百年的科學又是因為甚麼發展起來的呢?當然這是個太難答的問題,不過由尼丹約瑟的書的背面,是否可以看出另一個假設,即是:歐洲近五百年的科學發展主要是為了「好奇」。

說是為「好奇」,也許太專門,不易理解。就拿尼丹約瑟為例,他以半生時間跑完了中國,又淹在劍橋的書海裡,去發掘中國的科學史,這除了「好奇」,還能說出其他的原因嗎?

我們反過來問:我們能不能找到一個中國尼丹約瑟,以半生的時間,淹在南港的書庫裡,去研究歐洲的科學史來解答這個問題:「歐洲近五百年的科學發展主要是為了「好奇」。這個假說對呢?還是錯呢?」。

我掩卷凝思了半天,我想在中國找不出這樣一個「笨」人來。也就是說,在這種笨人不能產生之前,我們所謂的科學,還是抄襲的、短見的、實用的,也就是說,真正的科學是不會產生的。

從樓上望出去,劍橋就在眼前,劍河的水也並不是特別澄清,兩岸的樹也不是特別碧綠,崢嶸的樓頂,我們可以建,如茵的草地,我們可以鋪,我們同樣有不朽的藍天,同樣有瞬逝的雲朵,但培養這麼多人在這裡作好奇的夢,卻不是一蹴可幾的。

(一九六九年九月三十日寫於劍橋)

「我們反過問:我們能不能找到一個中國的尼丹約瑟,以半生的時間,淹在南港②的書庫裡,去研究歐洲的科學史來解答這個問題一一歐洲近五百年的科學發展主要是為了『好奇』?這個答案的假設是對呢?還是錯呢?」

「我掩卷凝思半天,我想在中國找不出這樣一個『笨』人來。也就是說,在這裡笨人未能產生之前,我們所謂的科學,還是抄襲的、短見的、實用的。也就是說,真正的科學是不會產生的」。......

1969

- The Grand Titration: Science and Society in East and West (1969) Allen & Unwin

- Within the Four Seas: The Dialogue of East and West (1969)

Chinese Accomplishments: The Grand Titration. Science and Society in East and West. Joseph Needham. Allen and Unwin, London, 1969. 352 pp. + plates. 63 s.

New Scientist is a magazine covering all aspects of science and technology. Based in London, it publishes weekly English-language editions in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia. An editorially separate organisation publishes a monthly Dutch-language edition. First published on 22 November 1956, New Scientist has been available in an online form since 1996.

Sold in retail outlets (paper edition) and on subscription (paper and/or online), the magazine covers news, features, reviews and commentary on science, technology and their implications. New Scientist also publishes speculative articles, ranging from the technical to the philosophical.

New Scientist was acquired by Daily Mail and General Trust (DMGT) in March 2021.[2]

"Darwin was wrong" cover[edit]

In January 2009, New Scientist ran a cover with the title "Darwin was wrong".[33][34] The actual story stated that specific details of Darwin's evolution theory had been shown incorrectly, mainly the shape of phylogenetic trees of interrelated species, which should be represented as a web instead of a tree. Some evolutionary biologists who actively oppose the intelligent design movement thought the cover was both sensationalist and damaging to the scientific community.[34][35]

註:

①尼丹約瑟,又名李約瑟。英國人,牛津名教授,曾在中國三十多年研究中國科學史,著有『東西方的科學家與社會』一書。此書已經由陳立夫先生帶領十數位翻譯家,將書譯成中文版。②南港在台北郊區,是台灣最高學術機關「中央研究院」的所在地。

李約瑟,CH,FRS,FBA(英語:Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham,1900年12月9日-1995年3月24日),原文名諾爾·約瑟夫·泰倫斯·蒙哥馬利·尼德漢,漢名李約瑟,

OVERVIEW

theory of types

QUICK REFERENCE

Russell's own reaction to his paradox of the class of all classes that are not members of themselves (see Russell's paradox) was to suggest that the definition is ill-formed because it involves the illegitimate notion of ‘all classes’. If the entities of a theory are classified in a hierarchy, with individuals at the lowest level, sets of individuals at the next, sets of sets further up again, and if prohibitions are introduced against sets containing members of different types, then the paradox cannot be formulated.

When Russell published his solution he was also influenced by Poincaré's constructivist response to the contradictions of set theory. This suggested that in any application of the axiom of comprehension, (∃y)(∀x)(x ∈ y ↔ Fx), the variable x should not range over entities including the set y. If it does, the definition becomes impredicative, and offends against the vicious circle principle. To prohibit this, Russell sorted predicates into orders, again with restrictions on wellformedness. The result is called the ramified theory of types. Unfortunately it proved impossible to construct classical mathematics within the ramified theory, and Russell was forced to introduce the axiom of reducibility, whose effect is to collapse the hierarchy of predicates.

Although the non-ramified or simple theory of types has attracted much subsequent work, all type theory suffers from a problem of unintuitive duplication. Thus for Russell there exists not one but an infinite number of the number 2, since there are sets of all sets having two members at each level in the hierarchy. Expressions needed at each type level, such as ‘=’, are supposedly systematically ambiguous, and in some developments there are an infinite number of identity symbols.

The relative consistency of type theory has been proved within Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, thereby also showing that the latter is stronger than the former. Few logicians now believe that there is any reason to build type restrictions into the formal systems within which set-theoretic and mathematical reasoning is best represented.

十三 不鑄大錯

June 16, 1874: Opening of the Cavendish Laboratory

The world-famous Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge has been home to scores of renowned scientists and profound breakthroughs, garnering 30 Nobel Prizes over the course of its history. Officially opened on June 16, 1874, the lab’s moniker honors the 18th century physicist and chemist Henry Cavendish.

Born in October 1731 to great wealth and status, Henry Cavendish had a noble lineage that traced back to the Norman era. His father was Lord Charles Cavendish, and his mother, Lady Anne de Grey, died when he was just two years old. Young Henry attended a private school just outside of London, and studied at St. Peter’s College, University of Cambridge, although he left the school after three years, having never earned a formal degree. Instead, he joined his father in London, and set up his own home laboratory.

It was Henry’s father who introduced him to the meetings of the Royal Society, and Henry was elected as a member in 1760. He served on numerous committees, and published his first paper in 1766. He was well respected, but also a notoriously shy man, typically speaking only to one person at a time, and largely avoiding women entirely. (He left notes as instructions for his female servants.)

Cavendish is perhaps best known for the discovery of hydrogen, which he dubbed “inflammable air,” produced when adding certain acids to specific metals. Other noted scientists like Robert Boyle had produced hydrogen, but it was Cavendish who realized it was an element. He also correctly identified carbon dioxide as exhaled (or “fixed”) air, and produced it in the laboratory, along with other gases. He won the Royal Society’s Copley Medal for his 1778 paper titled "General Considerations on Acids."

William Cavendish

When his father died, Henry began dividing his time between a house in London and a home in Clapham Common, which is where he kept his scientific instruments and performed most of his experiments. Neighbors told their children that the house was “where the world was weighed,” because that was Cavendish’s most famous experiment. He used a modification of the torsion balance built by geologist John Michell to determine the density of the Earth, publishing his results in 1798. His experiment was so precise that the value he obtained was within one percent of the current modern value.

Home laboratories like Cavendish’s were the norm for centuries of science history, and there was little infrastructure for educating students, apart from serving as an apprentice to a recognized scientist. The famous mathematician Isaac Todhunter summed up the prevailing attitude of the era when he opined, “Experimentation is unnecessary for the student. The student should be prepared to accept whatever the master told him.”

Attitudes began to shift in the mid-19th century, when William Thompson (Lord Kelvin) set up a physical laboratory in an old wine cellar for his students, although there was still very little in the way of formal instruction. By 1869, Oxford University had begun to build its Clarendon Laboratory, and a Cambridge committee issued a report calling for the establishment of a similar physical laboratory.

Unfortunately, there were insufficient funds to realize the committee’s vision, which called for “the founding of a special Professorship, and of supplying the Professor with the means of making his teaching practical—in other words, of giving him a demonstrator, a lecture room, a laboratory, and several class-rooms, with sufficient stock of apparatus.”

Eventually the wealthy university chancellor, the seventh Duke of Devonshire, donated the funds, and a then-relatively unknown young physicist named James Clerk Maxwell was selected as the first professor of experimental physics.

Henry Cavendish died in 1810, having never published the bulk of his scientific findings. But Maxwell took on the task of publishing the papers on the Cavendish electrical experiments in 1879, 100 years after those experiments were first conducted. Cavendish had anticipated such central concepts as electrical potential (although he called it the “degree of electrification”); Ohm’s law; Coulomb’s law; Richter’s law of reciprocal proportions; and the concept of the dielectric constant of a material, among other discoveries attributed to other scientists.

Cavendish had even drafted a manuscript describing his mechanical theory of heat that prefigured modern thermodynamics. Maxwell was so impressed with the work that he renamed the laboratory after Cavendish. It was particularly apt since the founding Duke of Devonshire, William Cavendish, was a member of the same family.

Maxwell died young, at 48, before the full revolutionary import of his work on electricity, magnetism, and statistical physics became clear. (When Albert Einstein was told by a Cambridge host that he had accomplished great things by standing on the shoulders of Newton, Einstein replied, “I stand on the shoulders of Maxwell.”) He was succeeded by another prominent physicist, J. J. Thomson, who discovered the electron.

Thomson in turn was succeeded by Ernest Rutherford, and it was under his leadership that James Chadwick discovered the neutron in 1932, and his students, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton, split the atom. When Lawrence Bragg took over, he focused on x-ray crystallography and his research and the later crystallographic work of Rosalind Franklin eventually led to the discovery of the structure of DNA in 1953 by Francis Crick and James Watson.

Initially located in the center of Cambridge, the Cavendish Laboratory grew so rapidly that overcrowding became an issue, and it was moved to West Cambridge in the 1970s. A third site is currently under construction. The research focus is now in such areas as nanotechnology, cold atoms, and ultra-low-temperature physics, and no doubt there will be even more pioneering breakthroughs in the laboratory’s future.

Further Reading:

Longair, Malcolm. Maxwell’s Enduring Legacy: A Scientific History of the Cavendish Laboratory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

歷史[編輯]

卡文迪許實驗室是近代科學史上第一個社會化和專業化的科學實驗室。它的建立標誌著實驗室已不再局限於科學家私家住宅中的地下室和閣樓。

1937年拉塞福去世後,布拉格接替他成為實驗室主任。當時,核物理學需要大量資金建造新的儀器,世界核物理學的研究中心已經開始向經濟實力雄厚的美國轉移。布拉格上任後,實驗室的主要研究方向從原本擅長的核物理轉向固態物理學。此外,他還大力支持新興的邊緣學科,如用X射線繞射方法研究蛋白質和DNA等生物大分子,利用英國空軍廢棄的雷達改造成無線電望遠鏡研究天體物理,後來卡文迪許實驗室獲得的兩個諾貝爾獎都與此有關。

歷任主任[編輯]

歷任實驗室主任(卡文迪許物理學教授)[2]:

- 1871年 - 1879年:詹姆士·馬克士威

- 1879年 - 1884年:約翰·斯特拉特,第三代瑞立男爵

- 1884年 - 1919年:約瑟夫·湯姆森

- 1919年 - 1937年:厄尼斯特·拉塞福

- 1938年 - 1953年:威廉·勞倫斯·布拉格

- 1954年 - 1971年:內維爾·莫特

- 1971年 - 1982年:布萊恩·皮帕爾德

- 1983年 - 1995年:薩姆·愛德華

- 1995年 - 今:理察·弗倫德

重要的研究成果[編輯]

- 1897年,約瑟夫·湯姆森研究陰極射線時發現電子。

- 1935年,詹姆士·查兌克發現中子。

- 1937年,喬治·湯姆森進行電子繞射實驗,證明波粒二象性。

- 1953年,詹姆士·華森與佛朗西斯·克里克發現脫氧核糖核酸(DNA)的雙螺旋結構,1962年獲得諾貝爾生理學或醫學獎(另一位獲獎者莫里斯·威爾金斯屬於倫敦大學國王學院)。

- 1974年,喬絲琳·貝爾及其導師安東尼·休伊什發現脈衝星。

Nobel Laureates at the Cavendish[edit]

- John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh (Physics, 1904)

- Sir J. J. Thomson (Physics, 1906)

- Ernest Rutherford (Chemistry, 1908)

- Sir William Lawrence Bragg (Physics, 1915)

- Charles Glover Barkla (Physics, 1917)

- Francis William Aston (Chemistry, 1922)

- Charles Thomson Rees Wilson[15] (Physics, 1927)

- Arthur Compton (Physics, 1927)

- Sir Owen Willans Richardson (Physics, 1928)

- Sir James Chadwick (Physics, 1935)

- Sir George Paget Thomson[16] (Physics, 1937)

- Sir Edward Victor Appleton (Physics, 1947)

- Patrick Blackett, Baron Blackett (Physics, 1948)

- Sir John Cockcroft[17] (Physics, 1951)

- Ernest Walton (Physics, 1951)

- Francis Crick (Physiology or Medicine, 1962)

- James Watson (Physiology or Medicine, 1962)

- Max Perutz (Chemistry, 1962)

- Sir John Kendrew (Chemistry, 1962)

- Dorothy Hodgkin[18] (Chemistry, 1964)

- Brian Josephson (Physics, 1973)

- Sir Martin Ryle (Physics, 1974)

- Antony Hewish (Physics, 1974)

- Sir Nevill Francis Mott (Physics, 1977)

- Philip Warren Anderson (Physics, 1977)

- Pyotr Kapitsa (Physics, 1978)

- Allan McLeod Cormack (Physiology or Medicine, 1979)

- Mohammad Abdus Salam (Physics, 1979)

- Sir Aaron Klug[19] (Chemistry, 1982)

- Didier Queloz (Physics, 2019)

Cavendish Professors of Physics[edit]

The Cavendish Professors were the heads of the department until the tenure of Sir Brian Pippard, during which period the roles separated.

- James Clerk Maxwell FRS FRSE 1871–1879

- John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh[20] 1879–1884

- Sir Joseph J. Thomson FRS 1884–1919

- Ernest Rutherford FRS, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson 1919–1937

- Sir William Lawrence Bragg CH OBE MC FRS 1938–1953

- Sir Nevill Francis Mott CH FRS 1954–1971

- Sir Brian Pippard FRS[21] 1971–1984

- Sir Sam Edwards FRS 1984–1995

- Sir Richard Friend FRS FREng[22] 1995–present

Entrance at the original Cavendish Laboratory site on Free School Lane

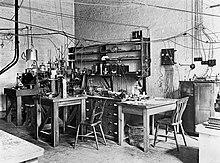

Sir Ernest Rutherford's physics laboratory- early 20th century

Southern aspect of the laboratory at its current site, viewed from across 'Payne's Pond'

The third iteration of the Cavendish Laboratory under construction in 2020 on its new site at JJ Thomson Avenue

沒有留言:

張貼留言