Capturing Kandinsky: The Women behind the Camera

A lot is known about Vasily Kandinsky. He originally studied law, economics, anthropology, and ethnography before he began to focus on art around the age of thirty. He was a promulgator of European abstraction, his works heavily influenced by music and spirituality. He was inspired by his contemporaries, his practice evolving as he moved from Germany to his homeland of Russia, back to Germany, and then on to France.

And he was not shy about having his picture taken.

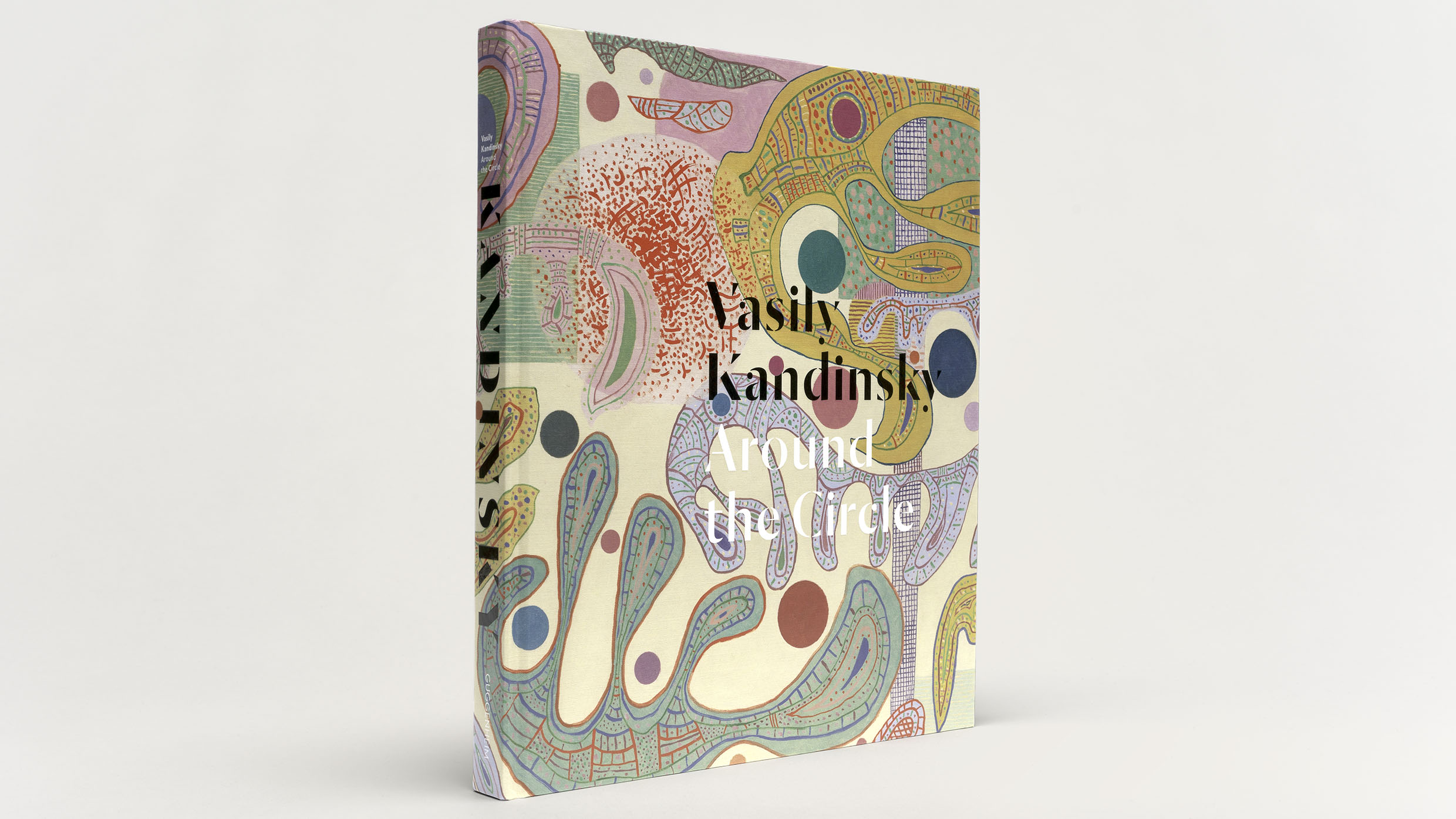

Toward the end of the Guggenheim publication Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle is a detailed timeline of the artist’s life, from his childhood in Russia to his final days in France. Interspersed throughout the pages, black-and-white photographs show Kandinsky at moments in his life. In one, he sits on a grassy hillside, engrossed in his sketching. In another, he stands with fellow artists Katherine S. Dreier and Marcel Duchamp on a train platform in Dessau, a cigarette in hand.

These rich photographic records provide a glimpse of the person behind the art. And several of them exist thanks to three women who documented and, intentionally or unintentionally, preserved his life and legacy.

Gabriele Münter

Gabriele Münter, whom Kandinsky met in 1901 when she became his painting student at the Phalanx-Schule in Munich, is often referred to as Kandinsky’s “companion,” her presence overshadowed by that of her more famous colleague and friend. But she was an artist in her own right. A German Expressionist painter and cofounder of Der Blaue Reiter, Münter approached stylized landscapes, still-life tableaux, and self-portraits with bold color palettes and strong, simple lines.

Prior to studying with Kandinsky, Münter was an avid sketcher and photographer, although she frequently dismissed the artistic nature of these works, regarding them as mere records of reality—just a means of reproducing the world around her. In fact, Kandinsky was quicker to embrace the idea of photography as an art form than she was.

That said, Münter was a prolific photographer. She became well versed in the medium during a two-year trip to the United States at the turn of the twentieth century, and she carried her Kodak camera throughout her fourteen-year-long relationship with Kandinsky. Her photographs from this period reflect their life together, one filled with exploration and innovation. She documented their travels across Europe and North Africa, their summers in Murnau in the Bavarian countryside, and the artists associated with Der Blaue Reiter together and at work—including Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Alexei Jawlensky.

Although their companionship ended sourly, Münter would help preserve Kandinsky’s artistic legacy, though perhaps not intentionally. Her photographs provide critical context as to his daily life and practices, as well as the impact travel had on his work. After Kandinsky returned to Moscow at the start of World War I, however, correspondence between the two artists waned, and in 1917, Münter discovered that Kandinsky had married Nina Andreevskaya. Still, during World War II, Münter risked her life to protect from the Nazis a collection of works by Kandinsky and other Blaue Reiter artists. These were among the more than one thousand works that she donated to the Lenbachhaus Museum in Munich upon her death in 1962.

Lucia Moholy

Like Münter, Lucia Moholy (née Schulz) spent much of her early career in the shadows of her partner, the artist and photographer László Moholy-Nagy. Also like Münter, Moholy documented a critical period in Kandinsky’s career.

After marrying in 1921, Moholy and Moholy-Nagy moved to Weimar, Germany, in 1923, so Moholy-Nagy could begin teaching at the Bauhaus, the progressive art, architecture, and design school. While her husband taught, Moholy focused on her own art and photography. She produced around six hundred images of the school’s iconic architecture and notable artists, including Kandinsky, who joined the faculty in 1922 and taught there until 1933.

Kandinsky’s Bauhaus period was one of the most productive in his career. It was during this time, living next door to Moholy and Moholy-Nagy, that Kandinsky began to refine his thinking around art’s correspondence to the spiritual. Influenced by his contemporaries—such as Klee and music theorist Gertrud Grunow—Kandinsky explored the relationship between form, color, and sound. It was also during this period that he reached international acclaim; artist Hilla Rebay escorted her US patron, Solomon R. Guggenheim, to the Bauhaus to meet Kandinsky, and she promoted his work in the United States, as did other enthusiasts, including Dreier and art dealer Galka Scheyer.

Though Moholy meticulously documented the Bauhaus, Moholy was deeply unhappy in the small town of Dessau, where the school moved in 1925. “Dessau was like a place where you travel, miss the train, and are forced to wait for the next one,” she wrote in her diary in 1927. She soon was able to convince Moholy-Nagy to move to Berlin, but the two of them ultimately parted ways in 1929.

When she was forced to leave Germany in 1933 due to her Jewish heritage, Moholy entrusted Moholy-Nagy with her photographic negatives; when he fled Germany, he in turn left the negatives with Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus’s founder and former director. Gropius brought the negatives with him to the United States and used them for a 1938 Bauhaus exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York—without receiving Moholy’s permission or giving her credit. (She also lent her editorial skills, without acknowledgment, to the creation of several books that either Moholy-Nagy or the school produced.) It took Moholy nearly twenty years to recover her work from Gropius and even longer to receive recognition for preserving the Bauhaus’s history and legacy, from its vanguard architecture to its vibrant community.

Nina Kandinsky

Not long after returning to Moscow at the start of World War I, and while still corresponding with Münter, Kandinsky received a phone call from a young woman, Nina Andreevskaya, an acquaintance of his nephew. Their conversation inspired him to paint To the Unknown Voice (1916). Less than a year after meeting, Kandinsky and Andreevskaya married, and they remained together until his death.

The first few years of their marriage—which coincided with the end of World War I and the beginning of the Russian Revolution—were marked by depravation and other socioeconomic difficulties, but the time they spent together at the Bauhaus in Germany was fruitful for the artist. While her husband thrived in his teaching role, Nina Kandinsky supported and recorded his activities, including when he met the Guggenheims and Rebay in the summer of 1930.

Following the closure of the Bauhaus in 1933 due to pressure from the Nazi party, the Kandinskys moved to Neuilly-sur-Seine, a suburb of Paris. Kandinsky continued to paint, completing his last large-scale canvas, Composition X (Komposition X), in early 1939, roughly five years before his death. Concurrently, Vasily Kandinsky’s works continued to be included in exhibitions in France and abroad, including Art of Tomorrow, the inaugural 1939 exhibition at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, the forerunner to the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Despite the nearly three decades that the Kandinskys spent together, little is known about the woman who partnered with the renowned artist through the latter half of his career. She kept her real birth year secret, and it is marked as unknown on her tombstone; she reportedly claimed to want to remain twenty forever and thus refused to celebrate any birthday beyond that one. The circumstances of her death in 1980 also remain a mystery. Details about her relationship with her husband can be gleaned from her memoir, Kandinsky und ich (Kandinsky and me), published in 1973, although many the stories in the book could be described as hyperbolic.

While not an artist herself, Nina Kandinsky’s photographs—both the ones she took and the ones she preserved—paint a picture of a full life. When Vasily Kandinsky died in 1944, Nina Kandinsky was his sole heiress. He left her a large collection of works, sketches, correspondences, books, and photographs—many of which she bequeathed to the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Now, almost 80 years after Vasily Kandinsky’s death, it’s still possible to discern intimate details about his life: the appearance of his desk, the posture he assumed when presenting his work, the joy he exuded when interacting with his friends and colleagues. Together, Gabriele Münter, Lucia Moholy, and Nina Kandinsky developed a comprehensive portrait of one of the 20th century’s most prominent artists.

Explore the evolution of Kandinsky’s practice in the exhibition Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle, on view at the Guggenheim Museum through September 5, 2022.

Vasily Kandinsky: Around the Circle

Published in 2021

知心集:20世紀佳偶(1); Bauhaus 群英傳 (7): Josef Albers (1888~1976 ) /Josef and Anni ALBERS (1899-1994)

序曲:

知心集:20世紀佳偶(1); Bauhaus 群英傳 (7): Josef Albers (1888~1976 ) /Josef and Anni ALBERS (1899-1994)

"I prefer to see with closed eyes."

Josef Albers (1888 – 1976)

ART REVIEW

Homage to Mexico: Josef Albers and His Reality-Based Abstraction

A radiant Guggenheim exhibition grounds the proto-Minimalist abstract paintings of Josef Albers in the geometric grandeur of Mesoamerican monuments.

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/14/arts/design/josef-albers-mexico-guggenheim-museum-homage-to-the-square-mesoamerica.htmlAnniAlbers (1899-1994) was one of the most influential #textile designers of the last century and a leader of the #bauhaus #modern #weaving movement > Discover Bauhaus #Rugs https://bit.ly/31oHbfw

約瑟夫

kh.edu.tw

https://www.hcvs.kh.edu.tw › news

亞伯斯(Josef Albers, 1888~1976)是二十世紀最重要之藝術家與教育家之一,高雄市立美術館與約瑟夫與安妮.亞伯斯基金會(The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation)合作, ...

【高雄市立美術館】極簡大用:包浩斯巨匠亞伯斯 - YouTube

YouTube

https://www.youtube.com › watch

0:41

約瑟夫.亞伯斯(Josef Albers, 1888~1976)是二十世紀最重要之藝術家與教育家之一,高雄市立美術館與約瑟夫與安妮.亞伯斯基金會(The Josef and Anni ...

YouTube · Wisely wei · May 11, 2010

是藝術教會了我們勇氣:紡織藝術家Anni Albers 與丈夫Josef ...

wonder.am

https://wonder.am › 2022/01/03 › a...

Jan 3, 2022 — 提到安妮・阿爾伯斯(Anni Albers),不可否認地,她被公認是二十世紀最重要的紡織藝術家之一,她足以撼動時代的創新力與影響力,來自於將現代主義的 ...

蘭萱播音室- 約瑟夫.亞伯斯(Josef Albers, 1888~1976) ...

https://m.facebook.com › photos

約瑟夫.亞伯斯(Josef Albers, 1888~1976)是二十世紀最重要之藝術家與教育家之一,高雄市立美術館與約瑟夫與安妮.亞伯斯基金會(The Josef and Anni Albers...

沒有留言:

張貼留言