"關鍵少數思考學習法"分析社會大運動:新俄革命前後(1910~1930) 俄羅斯幾多精英(馬勒維奇(Kasimir Malevitch)和塔特林(Tatline)......)互動 (1): 四城市:維捷布斯克(Vitebsk)市聖彼得,莫斯科, Kazan (Volga region) 。以20 世紀名藝術家夏卡爾(Marc. Chagall, 1887-1985)為例出發 ;新俄革命前後的前衛藝術,社會参與群英:以有中文資料的書出發,簡介台大圖書館的英文資料等。

Bruce Chatwit 《The Volga伏爾加河》 Kazan (Volga region) Federal University 校友 列寧革命、夫婦美學修養 對前衛藝術的容忍 ,托爾斯泰 RODCHENKO AND POPOVA。 高爾基故事。俄羅斯建築師康斯坦丁·梅爾尼科夫 (Konstantin Melnikov) 蘇聯館是1925世博會 , 70年代Bruce Chatwit 訪問Konstantin Melnikov: Architect 1988 莫斯科家/梅爾尼科夫之家Melnikov Houseelnikov: solo architect in a mass society.1978

俄國藝術收藏家 George Costakis (科斯塔基斯 1913~90 )等3人 https://www.facebook.com/hanching.chung/videos/1701546183961972

Artistic inspiration

[edit]

Goodman notes that during that period in Imperial Russia, Jews had two ways to join the art world: one was to "hide or deny one's Jewish roots", the other—the one that Chagall chose—was "to cherish and publicly express one's Jewish roots" by integrating them into art. For Chagall, that was also his means of "self-assertion and an expression of principle".[23]: 14

Chagall biographer, Franz Meyer, explains that with the connections between his art and early life "the hassidic spirit is still the basis and source of nourishment for his art".[27] Lewis adds: "As cosmopolitan an artist as he would later become, his storehouse of visual imagery would never expand beyond the landscape of his childhood, with its snowy streets, wooden houses, and ubiquitous fiddlers... [with] scenes of childhood so indelibly in one's mind and to invest them with an emotional charge so intense that it could only be discharged obliquely through an obsessive repetition of the same cryptic symbols and ideograms... "[16]

Years later, at the age of 57, while living in the United States, Chagall confirmed that when he published an open letter entitled, "To My City Vitebsk":

Art career

[edit]Russian Empire (1906–1910)

[edit]In 1906, he moved to Saint Petersburg, which was then the capital of the Russian Empire and the center of the country's artistic life, with famous art schools. Since Jews were not permitted into the city without an internal passport, he managed to get a temporary passport from a friend. He enrolled in a prestigious art school and studied there for two years.[22] By 1907, he had begun painting naturalistic self-portraits and landscapes. Chagall was an active member of the irregular freemasonic lodge, the Grand Orient of Russia's Peoples.[29] He belonged to the "Vitebsk" lodge.

Between 1908 and 1910, Chagall was a student of Léon Bakst at the Zvantseva School of Drawing and Painting. While in Saint Petersburg, he discovered experimental theater, and the work of such artists as Paul Gauguin.[30] Bakst, also Jewish, was a designer of decorative art and was famous as a draftsman designer of stage sets and costumes for the Ballets Russes, and helped Chagall by acting as a role model for Jewish success. Bakst moved to Paris a year later. Art historian Raymond Cogniat writes that after living and studying art on his own for four years, "Chagall entered into the mainstream of contemporary art. ...His apprenticeship over, Russia had played a memorable initial role in his life."[31]: 30

Chagall stayed in Saint Petersburg until 1910, often visiting Vitebsk where he met Bella Rosenfeld. In My Life, Chagall described his first meeting her: "Her silence is mine, her eyes mine. It is as if she knows everything about my childhood, my present, my future, as if she can see right through me."[22]: 22 Bella later wrote, of meeting him, "When you did catch a glimpse of his eyes, they were as blue as if they'd fallen straight out of the sky. They were strange eyes … long, almond-shaped … and each seemed to sail along by itself, like a little boat."[32]

France (1910–1914)

作者:

馬爾謝索, (Marchesseau, Daniel, 1947-), 著

出版商 :

時報文化,

出版年份 :

臺北巿 : 時報文化, 2002[民91]

主題 :

繪畫家 -- 俄國 -- 傳記 夏卡爾, (Chagall, Marc, 1887-1985) -- 作品集 -- 批評, 解釋等, 夏卡爾, (Chagall, Marc, 1887-1985) -- 傳記,

格式:

圖書

1887年7月7日,在離立陶宛邊境不遠的白俄羅斯維捷布斯克(Vitebsk),莫伊希‧塞加爾(Moyshe Segal)誕生在一個講意第緒語(Yiddish)的猶太教哈西德(Hassidic)教派家庭中。父親扎哈爾(Zakhar)是鯡魚店的夥計,母親費加-伊塔(Feiga-Ita)經營雜貨舖。夏卡爾(Marc Chagall)日後將邁出大步,跨出傳統源遠流長的猶太村落,離開貧民區,開創他充滿想像的世界。

第一章 離開維捷布斯克

曾在1812年遭拿破崙入侵的維捷布斯克,生活冷酷而艱難。世紀之交的年代裡,這裡是沙皇俄國最大的猶太社區之一,猶太人幾乎占五萬人口的一半。貫串夏卡爾一生,維捷布斯克一直是他童年的珍愛形象。直到他晚年的作品中,仍不斷藉著畫筆,重現寒冷北國陽光下洋蔥頂教堂的記憶。

夏卡爾在九個孩子中排行老大,長期拿家人當繪畫的模特兒。他們構成他內在世界的一部分,以模特兒身分參與他的繪畫世界。1922年,他在自傳《我的一生》(Ma Vie)中略帶幽默地描述自己貧窮卻溫馨的童年,日後成為他繪畫的素材。在這本自傳的獻辭中,他寫道:「獻給我的父母、我的愛妻,以及我的故鄉。」

在猶太傳統中成長

小夏卡爾誕生在一個貧窮的猶太區,靠近佩斯科瓦蒂克(Pestkowatik)大道,前面是監獄和精神病院。也許是命運的徵兆,他出生時拖了很久,遲遲生不出來,此時附近忽然發生大火,於是剛出生的嬰兒就被放在飼料槽中:「首先躍入我眼簾的是飼料槽,樣子簡單,呈正方形,一半凹進去,一半是橢圓狀,就是市集上普通的飼料槽。一放進去,整個飼料槽都被我填滿了。」《我的一生》於焉啟幕。

夏卡爾的祖父是猶太教堂的教師和唱經班成員,父親則是直率而沈默寡言的勞動者,夏卡爾日後常把他描繪為虔誠的猶太人原型:身穿長禮袍,套著祈禱者的圓翻領(帶流蘇的披巾),配戴祈禱用的經文帶,左臂上纏著祈禱用的經文護符繩飾,隨著聖詩誦唱的節奏,前後搖晃。

在那個貧困拮据的年代裡,婦女得艱辛地操持家務。夏卡爾的母親很能幹,原是遼茲諾(Lyozno)祭典屠戶之女。夏卡爾永遠感謝母親的一點,就是她即使不算鼓勵、也是接受了他想當畫家的志向:「是啊,孩子,我明白,你有天分……這種天分是從哪來的?」30年後,夏卡爾在自傳《我的一生》中回答了母親,他在書中驕傲地提及傑出的先祖塞加爾(Chaim Ben Isaac Segal),早在一百年前,烏克蘭的莫希列夫(Mohilev)一座美麗的猶太教堂的壁畫,就是出自這位祖先之手。

發現志向

1895年,夏卡爾年僅八歲,俄國爆發新一波的猶太大屠殺。夏卡爾擁有多方面才華,夢想同時成為歌唱家、舞蹈家、音樂家、詩人……和畫家。所有的親友、家務雜事和鄰近的街坊,後來都成為他描摩的對象:屠夫、警察、小販、理髮店、雜貨店、銀行、動物,都構成了他的藝術世界。

全家人虔誠遵循哈西德教派奠基於對鄰人之愛的教規。每個紀念活動,如:安息日(Sabbath)、普林節(Purim)、住棚節(Succoth)、贖罪日(Yom Kippur)等都要受到尊重。父母都是文盲的小夏卡爾起先進入傳統猶太小學就讀,學習希伯來語和以聖經為根據的歷史。沙皇俄國禁止猶太小孩進入一般公立小學,但是母親憑一席酒菜,讓夏卡爾得以在13歲那年進入普通中學,學習俄語和幾何學。這段時期形塑了他意第緒語-俄語的雙語表達方式,後來又學會法語,使得他講話中帶有無法模仿的詞彙和口音,且因微微口吃更顯獨特。

▼ 書摘 2

啟蒙時期

1906年,19歲的夏卡爾進入畫家耶烏達‧潘(Yehuda Pen)在維捷布斯克市中心自宅開設的畫室學畫,前後兩個月。俄語也說得不好的潘,是小有名氣的學院派風景畫和肖像畫家。這段短暫的學藝期為年輕的夏卡爾留下深遠的影響。尤其他筆下的猶太人肖像,在履行宗教儀式時所顯現的專注神情,使人聯想起耶烏達‧潘的一些肖像畫;〈閱讀摩西五書〉、〈闡述猶太法典他勒目〉、〈戴無邊圓帽的老人〉……這段師徒關係只持續了很短的時間,但戰爭期間又重新開始:1917年,他們分別為對方畫肖像。即使早在1906年,夏卡爾就已經開始使用狂放不羈的色彩和基本上揚棄寫實主義的手法,使畫面顯得奇譎怪誕:「在潘老師那兒,我是唯一用紫色作畫的學生,這招好像很大膽,於是從那時開始,我就不用交學費了。」夏卡爾的父親實在太窮了,供不起兒子的志向。於是為了賺一點微薄的工資,夏卡爾得去替一個攝影師修底片。1907年,夏卡爾口袋裡只有27個盧布,終於出發去俄國首都聖彼得堡。當時在涅瓦河(Neva)沿岸嚴格執行反猶太法令:只有持有特殊許可證的藝術家,才能在那裡居住。

藝術贊助人高德堡(Goldberg)律師名義上雇用夏卡爾為僕人,好讓他能在首都居留,並註冊進入入「帝國協會美術學校」學習修護美術品。然而有天晚上,夏卡爾因為沒有將過期的居留許可證換新,遭到了一頓毆打,還被關進監獄15天。

莫伊希‧塞加爾在聖彼得堡

夏卡爾很高興的發現了亞歷山大三世的博物館,看到修士畫家魯布列夫(Andrei Roublev)的聖像畫,讚歎道:「我們的文藝復興開拓者契馬布耶(Cimabue)」。

年方20歲時,夏卡爾便受到美術學校的年輕主任羅里希(Nicolas Roerich)極大鼓勵。1907年4月,羅里希讓夏卡爾得到緩征機會,隨後又免役,還獲得從1907年9月到1908年7月每月15盧布的助學金。

這位生平首次獲得優遇的年輕學生於是在這所私立美術學術待了一陣子,校長是受歡迎的風景畫家賽登柏格(Saidenberg),畫風是一般所謂的「巡迴畫派」。出身寒微、所受教育不多、又是外省人的夏卡爾生活十分拮据。他經常與其他窮人同享一張屋角的草墊子。在他的畫中,如同自傳《我的一生》所描述,那盞油燈和那把椅子成為他主要的象徵原型:「我不止一次懷著羨慕心情,注視桌上那盞點燃的煤油燈,暗自思忖,瞧,它燃燒得多麼自在愉快,它可以盡情的喝著煤油,而我呢……」

維納韋(Maxime Vinaver)是1905年革命後所成立的下議院杜馬(Douma)中頗具影響力的民主派議員,也是聖彼得堡的希伯來歷史與民族誌協會的領導人物。他成為夏卡爾的導師,安排他住在自己所編的猶太政治雜誌《黎明》(Voshod)的辦公室裡。不久,茲凡思瓦藝術學校校長暨畫家巴克斯特(Leon Bakst)接受他為學生。由茲凡思瓦(Elizaveta Nikolaievna Zvantseva)創辦的這所藝術學校,因為在現代藝術上的創見與開放而聞名一時;學生包括托爾斯泰伯爵夫人和舞蹈家尼金斯基(Vaslav Nijinsky)。

夏卡爾日後回憶,巴克斯特真正讓他感受到「歐洲氣息」,鼓勵他離開俄國去巴黎。從這段時期,夏卡爾開始脫離俄羅斯藝術圈,有別於那時當道的寓意畫像和某些藝術理論,夏卡爾已顯現其獨立的視野和孤僻的藝術形象,摒棄所有已知的藝術社團或藝術家團體,反倒使他有股傲然之氣。

投身俄國的現代藝術

夏卡爾在茲凡思瓦藝術學校學習了兩年,1909年春,當巴克斯特和畫家兼評論家貝努瓦(Alexandre Benois)這兩位後象徵主義團體「藝術世界」(Mir Iskousstva)的創建者到巴黎與芭蕾舞編舞家佳吉列夫(Sergey Diaghilev)會合時,夏卡爾便跟隨了更創新的藝術家多布金斯基(Mstislav Doboujinsky),多布金斯基是第一個向他引介梵谷和塞尚作品的人。

1910年春,夏卡爾在前衛雜誌《阿波羅》(Apollon)首次展出作品,並首度以畫作支持新形式的藝術,這在當時奉行學院派的保守寫實畫家列賓(Ilya Repin)看來,簡直是樁可恥的醜聞。

這種投入環境、體現時代精神的勇氣,可以視為全歐洲運動的一環。隨著1905年俄國在政治上的改朝換代,歷經幾次政治動盪後,藝術家們受到俄國向新潮流開放(尤其是向法國)的影響,重新組成前衛團體,反抗學院派。藝術雜誌在其中貢獻很大,它們刊登重要的藝術宣言,同時策畫畫展,比較俄法畫家的作品。因此,夏卡爾與同時期的畫家得以熟悉歐洲藝術令人眼花撩亂的發展,從野獸派的馬諦斯(Henri Matisse)、德漢(Andre Derain)和烏拉曼克(Maurice Vlaminck),以至德國的表現主義與義大利的未來派藝術家。

1907年在聖彼得堡,布流克(Bourliouk)兄弟與詩人馬雅科夫斯基(Vladimir Maiakovskii)建立俄國第一個未來主義團體,隨後與其他叛逆的藝術家,如拉里歐諾夫(Mikhail Larionov)、岡察洛娃(Natalia Gontcharova),馬勒維奇(Kasimir Malevitch)和塔特林(Tatline)一起參加1909年成立的「青年聯盟」。同年,拉里歐諾夫、岡察洛娃在莫斯科舉行第二屆「金羊毛」畫展的開幕式,同時也舉辦「自由美學」畫展。夏卡爾是聖彼得堡這如火如荼的新原始主義運動的見證者和參與者,後來在旅居巴黎期間,他繼續為那些早期朋友策畫的俄羅斯前衛派畫展寄送自己的作品,其中包括了〈驢子的尾巴〉這幅畫。

夏卡爾的技法發展包括不同階段,從強烈的俄羅斯野獸派到布流克兄弟的「立體-未來派」都有,顯示他在當時那種無人能逃避、狂熱欣喜的氣氛下,也能融合各家觀點。

「不可為自己雕刻偶像,也不可作甚麼形像、彷彿上天、下地、和地底下水中的百物。」(〈申命記5:8〉)

夏卡爾很早就棄絕了猶太傳統中嚴禁一切描述人物形象的破除偶像原則。他後來成為說故事者和意象畫家,將直到那時仍尚受語言局限的形式表現,訴諸於對猶太教和聖經訊息的懷念:現實與傳奇、夢幻與寓意,總之是始終曖昧隱晦、反差強烈的主題。這股傾心於融合現實和非理性、可見與不可見、民俗和傳奇的現代藝術的信念,這個昇華自己的主觀意念以獲得象徵的多義性、超越其根源的文化和儀典世界的使命,成為他復國的基本信念。夏卡爾這個天生的猶太人,隨著時代推進,變成最廣義的教徒。他拒絕所有教義,但懷著對猶太基督教的抽象信仰,擁抱永恆的上帝和仁慈的宇宙。

從他最早的油畫(1907-09)中,可發現他在技法上有明顯進步:〈死神〉、〈鄉村園遊會〉、〈聖徒之家〉、〈婚禮〉、〈誕生〉,這些對家庭情景的追憶,也都是具有熱情內涵和心靈力度的隱喻性構圖。從這些作品沉重晦澀的色調來看,與其說接近西方,還不如說是更接近東方的傳統。畫中建築的外形加上扭曲的透視法,類似於樸素藝術(Naive)或新原始主義(neo-Primitivist)繪畫,而人物刻意放大比例的表現主義方式,創造出一種莊嚴而夢幻的抒情,這是在同時代畫家中見不到的。

他的筆觸雖還不夠出色,但手法卻很謹慎且經過深思熟慮,帶著驚人的自信。色調大體上是陰暗的,但也透過少數幾乎呈乳白色的平面區塊而使畫面亮了起來。他的構圖透過切割空間並以奇異角度安排散點透視關係,顯示出罕見的成熟。這個時期的品味反映在仔細的觀察和對細節的偏好,尤其是在布面油畫上。

▼ 書摘 3

「維捷布斯克,我要離開你了……」

1910年8月,幾個月來一直慷慨解囊、後來又持續到1914年的維納韋又資助夏卡爾一筆為數不多的費用。夏卡爾終於可以離開俄羅斯去巴黎了。這趟初旅標示著他生命中的轉捩點,因為夏卡爾決定在法國首都定居。他的命運就此改觀了……

一到巴黎,莫伊希‧塞加爾就取了法文名字,從此改叫馬克‧夏卡爾(Marc Chagall)。他先借住在畫家愛倫堡(Ehrenburg)位於蒙帕納斯(Montparnasse)梅納街(Maine)18號的寓所裡。一如往常,他出入好幾所美術學校,包括一般通稱的「大茅屋」(Grande Chaumiere)和「調色盤」(La Palette),任教的有勒‧福康尼耶(Le Fauconnier)、格列茲(Albert Gleizes)、梅金傑(Jean Metzinger)和德‧謝貢查克(Dunoyer de Segonzac)。由於經濟拮据,他只好在不用的布、床單,甚至自己的襯衫上作畫。在〈小提琴手〉這幅畫中,還隱約可見露出花邊裝飾的襯底。

比起去畫室上課,夏卡爾更喜歡去羅浮宮,他與同時代的歐洲畫家一樣,從未研究過古代大師的作品。法蘭德斯(Flanders)和義大利文藝復興之前的古典美學準則,以及法國的偉大古典畫家,都構築了他的美學觀,解放他的色彩靈感。德拉克洛瓦(Eugene Delacroix)、傑利柯(Theodore Gericault)、庫爾貝(Gustave Courbet)、勒南兄弟(Le Nain)、華鐸(Antoine Watteau)、烏切羅(Paolo Uccello)、福格(Jean Fouquet)、夏丹(Jean Baptiste Chardin)……等,都是他的研究對象。

這段日子對離鄉背井、感到自我懷疑的夏卡爾來說,是段寂寞的時期。他喜歡在夜裡作畫,白天則去畫商伯恩罕(Bernheim)、杜杭-胡埃(Durand-Ruel)、佛拉(Ambroise Vollard)的沙龍和藝廊,研究印象派畫家魯東(Odilon Redon)、塞尚(Paul Cezanne)、高更(Paul Gauguin)和同時代畫家對空間和光的探索。他成為善於運用絢麗色彩的畫家,以驚人速度領悟野獸派的現代觀念。巴克斯特稱讚他:「現在你的色彩響亮了!」他從立體派借用解構的技巧,然而他仍懷疑這個技巧過於寫實。

桑德拉、阿波里奈爾與其他畫家

1911年底,這位被鄰居喊作「詩人」的畫家,遷居到「蜂巢」(La Ruche),這是一棟塞滿了破舊工作室的建築,群集著貧窮的藝術家,包括雷捷(Fernand Leger)、雕刻家羅杭(Henri Laurens)及許多外國藝術家;彼此往來,生活匱乏。還有夏卡爾的同胞:雕刻家阿奇賓科(Alexander Archipenko)、查德金(Ossip Zadkine)、畫家蘇汀(Chaim Soutine),以及作家薩爾門(Andre Salmon)、雅可伯(Max Jacob),他們日後都成為「巴黎畫派」(L’Ecole de Paris)的擁護者。

在「蜂巢」,夏卡爾認識了與他同齡的瑞士詩人桑德拉(Blaise Cendrars),他為人熱情,喜歡到處旅行,曾待過聖彼得堡,也了解俄國。夏卡爾移居巴黎初期,兩人迅速結為好友。桑德拉彷彿一把「光明熾熱的火焰」,與夏卡爾同甘共苦,成為他知性上的良師,還介紹他認識法國畫家德洛內(Robert Delaunay)和其俄裔妻子桑妮亞‧特克(Sonia Terk)。

當時桑德拉為夏卡爾的許多畫作構思出標題:〈獻給未婚妻〉、〈獻給俄羅斯、驢子和其他人〉、〈詩人,三點半〉……還將《快活詩集》(Poemes elastiques)中的兩首詩獻給夏卡爾,並在〈西伯利亞散文〉中聲稱:「就像我的朋友夏卡爾一樣,我可以創作出一連串錯亂顛狂的畫面。」

1912年,桑德拉也介紹他認識詩人阿波里奈爾(Guillaume Apollinaire):「這位溫柔的宙斯﹝…﹞,用詩句、數字和躍動的音節,為我們照亮道路。」他造訪夏卡爾畫室的過程足堪寫入歷史:「阿波里奈爾坐了下來,像捧著一套全集似地捧著自己的肚子﹝…﹞他漲紅臉,鼓起腮幫子,微笑地囁嚅著:『超自然!……』」他猜到畫家對「真實」所持的曖味態度。這個字眼也暗示著夏卡爾充滿力量而折衷的意象,出自如夢般的無意識。夏卡爾後來將〈亞當與夏娃〉這幅畫獻給阿波里奈爾、桑德拉、卡努多(Ricciotto Canudo)和瓦爾登(Herwarth Walden)。此作代表他創作中獨一無二富象徵性的敬意,流露出對四位熱情支持者的感激之情。

阿波里奈爾收到夏卡爾用紫色墨水所畫的肖像後,回贈他一首詩〈侯索吉〉(Rotsoge;法國超現實派詩人布荷東﹝Andre Breton﹞稱之為「本世紀最自由的詩!」),竟是草草寫在一張菜單背面!可惜的是,夏卡爾1914年在瓦爾登位於柏林的「狂飆」(Der Sturm)畫廊舉辦生平首次個展,阿波里奈爾之前曾承諾要寫展覽介紹,卻從未寫出。

「巴黎,有著獨一無二的鐵塔、絞刑架和摩天輪的都市」(桑德拉)

1910至14年間的蒙帕納斯,充滿了藝術家、詩人和波西米亞人,他們以自己獨特的方式,重新定義藝術的概念。之前曾被忽視的畫家如塞尚、高更和梵谷,以及晚期野獸派的狂暴色彩、立體派的激進意向、未來派勃發而出的宣言、奧菲主義(Orphism,色彩立體主義)的誕生,對夏卡爾這麼一個在繪畫感悟上正處於激烈動盪期的畫家來說,都是具決定意義的事件,他渴望在造型形式中確立自己的風格。必要的決裂讓他擺脫色彩的桎梏,簡潔而肯定地去實踐立體派的解構及效果,創作色塊狀的作品〈亞當與夏娃〉、〈各各他〉或〈耶穌受難像〉(1912)。

〈各各他〉是夏卡爾第一幅受猶太-基督教啟發的傑出油畫,代表最初超然的告解,色彩上也顯示出夏卡爾與同時代德國表現主義畫家及瑞士超現實畫家克利(Paul Klee)的連結。

特別的是,在德洛內和福康尼耶的堅持下,這件作品首先入選1912年秋季沙龍,1913年9月與〈獻給俄國、驢子和其他人〉及〈獻給未婚妻〉一起入選柏林第一屆「德國秋季沙龍」,於「狂飆」(Der Sturm)展出,後來被「藍騎士」(Der Blaue Reiter)畫派的贊助人、柏林收藏家科勒(Bernard Kohler)買下。

跟德洛內、馬庫西(Louis Marcoussis)、格列茲、拉弗里奈(Roger La Fresnaye)、梅金傑和勞特(Andre Lhote)一樣,夏卡爾也深入探索現代性的主題:〈艾菲爾鐵塔〉、〈摩天輪〉、〈窗外的巴黎〉。巴黎在夏卡爾這個俄國人眼中,具體表現了「光與色彩的驚人自由」。在豐富多元的社會政治背景下,兩種主題不斷出現:動物(母牛、公牛、山羊……)和頭倒置或身首分離的人物。夏卡爾用這種不合邏輯的抒情方式創新繪畫形式,日後還大量應用。

但25歲的他拒絕加入任何派別的藝術家團體,始終保持獨立不群的眼光,忠於自己的記憶。這種性格特徵,說明他仍想保有俄國人和猶太人的背景,廣義而言,就是刻意擺脫巴那斯派(parnassien)的巴黎腔,專注於聖像寓意畫。獨處畫室中,夏卡爾的思緒回到維捷布斯克(〈牲畜商〉與〈獻給俄國、驢子和其他人〉)和猶太人日常的宗教儀式(〈祈禱的猶太人〉)。移居巴黎的他已與這種儀式隔絕,巴黎的猶太人已愈來愈被同化而不奉行教事了。「我從俄國帶來創作主題,而巴黎則賦予它們光。」當時一位年輕記者、自由浪漫的思想家盧那察斯基(Anatoli Lounatcharski)寫了篇讚揚夏卡爾的文章刊登在基輔一家報紙上,而那位聖彼得堡的贊助人維納韋也幾次來到巴黎,對夏卡爾的作品深表滿意。

「我的藝術也許是荒誕的藝術,宛如一泓閃亮的水銀、一顆藍色靈魂迸發在畫布上」

於是夏卡爾的畫作彷彿夢境中的城邦,一些幻想人物出現在熟悉的萬神廟中,在樅木屋間大聲叫罵,寄宿的小提琴手、遮篷馬車、裝扮的母牛、點燃的燭台,茅屋頂上或金色圓頂上喝醉的士兵:如此眾多色彩繽紛、離奇可笑的熟悉形象,在生活與夢境的交織中發出聲響……茶炊的呼呼聲、雪橇的滑動聲、孩子的哭鬧聲,擠奶時散發的乳香是如此樸實愉悅,唯有夏卡爾能透過許多小幅不透明水彩畫來表現。令人不禁疑惑,他與「關稅員」盧梭(Henri Rousseau)的作品間那種遙遠的關係,是否啟發了阿波里奈爾寫出〈侯索吉〉中的哀傷詩句?

此外,很明顯的是,透過烙印著家鄉文化的想像世界,夏卡爾的作品為當時主導巴黎的立體派引入新的平衡。還有哪位畫家和詩人能以如此眩目的方式,為立體派的視覺語言注入新生命呢?德洛內等友人們驚訝於他精妙的幾何構圖,更震懾於其色彩的明亮,這些色彩因畫面融合了俄羅斯民間傳說軼事、非理性、心理異象而更顯強烈,照布荷東所說,這是「完全抒情的迸發。」相反於法國繪畫的和諧感,夏卡爾的畫呈現出一種平靜與世俗的愉悅。

「我的畫是占據我內心意象的安排」

立體派對於夏卡爾的影響,表現出來的不太是分割平面與形體、在同一平面上將不同元素重新並陳之類的技巧。他的畫面如同心理平面,夢想與現實以音樂的節奏聚集,捕捉了他對世界事物的重組結果,並藉由一連串隱喻,呈現出一種世俗的真實。

〈七根手指的自畫像〉描繪盛裝的畫家坐在畫架前,背對窗子,窗外可見艾菲爾鐵塔散發的光芒,而畫家正在畫〈獻給俄羅斯、驢子和其他人〉──奇幻版的維捷布斯克──在他頭的右邊,勾起記憶的雲霧中,浮現一座東正教教堂的清晰回憶。牆上有希伯來文字母:左邊是「巴黎」,右邊是「俄羅斯」,反映了他借用自立體派拼貼文字的現代美學技法,也是離鄉背井的青年時期、孤獨遊子的精神文化的(憂鬱?)自白。過去和現在並陳為一幅整體的意象,粧點以自身無意識的色彩,成為純詩意的語言。

因此夏卡爾作品中的變形,所具有的意義和同時代畫家(如畢卡索)不同。為了召喚回憶,畢卡索採取了重組的方式,而夏卡爾卻將真實事物並置與交疊,如同在夢醒後進行精神分析,而重新體驗。這種展示夏卡爾自我的魔法,在〈孕婦〉一作中重演。愛的幻想、想像和鄉愁,意在弦外地揭示畫家的贖罪形象,畫家本人的形象也在畫面右下方出現。

墨水和畫筆

旅居巴黎期間,夏卡爾的作畫技巧更加精進。他在一張張小畫紙上,用鉛筆或墨水快速畫下各種想法的草圖,毫不遲疑,也從不修改。幾幅大型素描、少許水彩,加上油畫,就是他在巴黎期間的每日生活內容。

由於貧窮,他在進行大幅油畫前,會先在卡紙上畫出小而詳盡的水彩作為草圖。他喜歡在各個方向上作畫,像個「修鞋匠」。這就加強了中心部分的重要性,減弱上下部分的意義,〈神聖趕車人〉(1912)被瓦爾登在柏林買下,便徵得畫家同意,以上下顛倒的方式懸掛。

夏卡爾也寫些手記,大半是俄文,偶爾用意第緒語,有時也用法語。他寫滿好幾本詩歌筆記,俄國風味十足,風格極為華麗,特色在使用故國的象徵和俚語。

巴黎的生活改變了他的個性。維納韋按月寄給他助學金,使他生活不虞匱乏,而同期畫家對他真心推崇,也讓他雄心勃勃……甚至還會炫耀。跟其他同學一樣,他一開始學畫的那幾年,就會面對鏡子練習,但從1910年代起,他的自畫像數量日益增多,自戀得讓他與同儕格格不入。這一來是因為他在異國(使用他不熟悉的語言)對身分認同的追尋,二來也想展現自己的多方面才華。

這些年,夏卡爾的友人如詩人雅可伯、評論家薩爾門和《歡樂山!》(Montjoie!)雜誌創辦人卡努多,他們的支持也讓夏卡爾日益得到大家認可。儘管收藏家杜賽(Jacques Doucet)因為他人的忠告,對夏卡爾的作品不感興趣,但夏卡爾還是於1914年4月30日與畫商馬貝爾(Charles Malpel)簽下第一份合約。待夏卡爾回到俄羅斯時,已是具有地位、載譽而歸的著名畫家了,於是敢在政治對手面前直抒己見。

【書摘 1|書摘 2|書摘 3|書摘 4|書摘 5】

俄國20世紀西方藝術收藏史

Constructivism

Constructivism, Russian artistic and architectural movement that was first influenced by Cubism and Futurism and is generally considered to have been initiated in 1913 with the “painting reliefs”—abstract geometric constructions—of Vladimir Tatlin. The expatriate Russian sculptors Antoine Pevsner and Naum Gabo joined Tatlin and his followers in Moscow, and upon publication of their jointly written Realist Manifesto in 1920 they became the spokesmen of the movement. It is from the manifesto that the name Constructivism was derived; one of the directives that it contained was “to construct” art. Because of their admiration for machines and technology, functionalism, and modern industrial materials such as plastic, steel, and glass, members of the movement were also called artist-engineers.

Artists closely associated with Constructivism

[edit]- Ella Bergmann-Michel – (1896–1971)

- Norman Carlberg, sculptor (1928–2018)

- Avgust Černigoj – (1898–1985)

- John Ernest – (1922–1994)

- Naum Gabo – (1890–1977)

- Moisei Ginzburg, architect (1892–1946)

- Hermann Glöckner, painter and sculptor (1889–1987)

- Erwin Hauer – (1926–2017)

- Hildegard Joos, painter (1909–2005)

- Gustav Klutsis – (1895–1938)

- Katarzyna Kobro – (1898–1951)

- Srečko Kosovel – (1904–1926)

- Jan Kubíček – (1927–2013)

- El Lissitzky – (1890–1941)

- Ivan Leonidov – architect (1902–1959)

- Richard Paul Lohse – painter and designer (1902–1988)

- Peter Lowe – (1938–)

- Louis Lozowick – (1892–1973)

- Berthold Lubetkin – architect (1901–1990)

- Thilo Maatsch – (1900–1983)

- Estuardo Maldonado – (1930–)

- Kenneth Martin – (1905–1984)

- Mary Martin – (1907–1969)

- Konstantin Medunetsky – (1899–1935)

- Konstantin Melnikov – architect (1890–1974)

- Vadim Meller – (1884–1962)

- László Moholy-Nagy – (1895–1946)

- Murayama Tomoyoshi – (1901–1977)

- Victor Pasmore – (1908–1998)

- Laszlo Peri – artist and architect (1899–1967)

- Antoine Pevsner – (1886–1962)

- Lyubov Popova – (1889–1924)

- Alexander Rodchenko – (1891–1956)

- Kurt Schwitters – (1887–1948)

- Franz Wilhelm Seiwert - (1894-1933)

- Manuel Rendón Seminario – (1894–1982)

- Willi Sandforth - (1922-2017) - German painter and designer

- Vladimir Shukhov – architect (1853–1939)

- Anton Stankowski – painter and designer (1906–1998)

- Jeffrey Steele – (1931–2021)

- Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg – poster designers and sculptors (1900–1933, 1899–1982)

- Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958)

- Władysław Strzemiński – painter (1893–1952)

- Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953)

- Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949)

- Vasiliy Yermilov (1894–1967)

- Alexander Vesnin – architect, painter and designer (1883–1957)

Bruce Chatwin, 蘇聯藝術收藏家 George Costakis (科斯塔基斯 1913~90 ) 的故事;

俄國革命後/蘇聯,左派藝術運動(畫家。建築師,詩人....... )興盛,直至1932年被官方禁掉。之後被掩沒是西方20世紀的發源地及其思想 (第一次世界大戰期間,世界藝術中心從巴黎移往蘇聯。)

20 世紀初期,整個歐洲的文化和政治氣候正處於變革狀態,思想跨越國界交叉傳播。許多法國立體主義和義大利未來主義作品被帶到俄羅斯展出。(In the early years of the 20th century the cultural and political climate of Europe as a whole was in a state of change with a cross-fertilisation of ideas across national boundaries. Many French cubist and Italian futurist works were being brought into Russia and exhibited.)

Stalinism

[edit]起初,弗拉基米爾·列寧領導下的布爾什維克革命支持新抽象藝術,但從1920年起,俄羅斯藝術家的自由日益受到限制。許多藝術家希望他們的作品能為新社會的創建做出貢獻,而其他藝術家,例如至上主義者,則繼續獨立工作。 1924年列寧去世,繼任蘇聯共產黨領導人的約瑟夫·史達林帶來了另一種藝術意識形態。 1932年,社會主義現實主義成為官方國家政策。正是在這樣的政治環境中,科斯塔基斯經歷了俄羅斯舊藝術文化的發展、壓制和最終瓦解。

(At first the Bolshevik Revolution under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin supported the new abstract art but from 1920 onwards the freedom of artists in Russia was increasingly curtailed. Many artists wanted their work to contribute to the creation of a new society whilst others, for example the Suprematists continued to work independently.

Lenin died in 1924 and Joseph Stalin who succeeded him as leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, brought about another art ideology. In 1932 socialist realism became the official state policy. It was within this political environment that Costakis experienced the development, suppression and final disintegration of the older art culture in Russia.)

蘇聯藝術家簡介。參考wiki{edia

Edward Lucie-Smith 91歲(2024)

- Lives of the Great Twentieth Century Artists (1985)

二十世紀偉大的藝術家 第九章 俄國藝術家The Russians 1999頁,106~132 | |

| |

- Movements in Art since 1945 (1969) 二次大戰後的視覺藝術 , 李長俊譯, 台北:大陸書店,1974

New rev. ed.

Edward Lucie-Smith.

Published 1984 by Thames and Hudson in London .

George Costakis: 1973年於The Sunday Times 發表Moscows Unofficial Art,一文,收入文集題為 The Story of an art collector in the Soviet Union.

關於 George Costakis (科斯塔基斯 1913~90 ) .維基百科

- Bruce Chatwin, Moscows Unofficial Art, Sunday Times, 6 May 1973

Timeline

1977

George Costakis donated 834 visual art worksto the State Tretyakov Gallery: 142 paintings and 692 graphic works; 51 icons, religious embroideries, and fresco fragments to the Andrey Rublev Museum of Ancient Russian Culture and Art; and 230 Russian folk toys made of clay, wood, bone, papier-mâché, and other materials to the Soviet Ministry of Culture (which later ceded them to the Tsaritsyno Museum-Reserve).

2000

The Greek government purchased from the Costakis family 1,277 works brought by Costakis from Russia which can now be found at the Thessaloniki State Museum of Modern Art.

2013

The collector’s daughter Aliki Costakis donated over 600 works and archival documents of Anatoly Zverev from George Costakis’ collection to AZ Museum.

At first he worked as a driver for the Greek Embassy until 1939, when relationships between Russia and Greece broke down due to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. After that he took up work as Head of Personnel for the Canadian Embassy.

The Costakis Collection

[edit]At first Costakis had collected the Masters of the Dutch School of Landscape Painters but modernist works by Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse soon became his main subject, then in 1946 he came across three paintings in a Moscow studio by Olga Rozanova . He described how, in the dark days after the war these brightly coloured paintings of the lost Avant-Garde:

- "... were signals to me. I did not care what it was... but nobody knew what anything was in those days." (Chatwin, 1977)

He was so struck by the powerful visual effect of the strong colour and bold geometric design which spoke directly to the senses, that he was determined to rediscover the Suprematist and Constructivist art which had been lost and forgotten in the attics, studios and basements of Moscow and Leningrad.

He hunted for 'lost' pictures, some that were rolled up and covered with dust. He met Vladimir Tatlin and befriended Varvara Stepanova. He tracked down friends of Kasimir Malevich and bought works by Liubov Popova and Ivan Kliun. He particularly admired Anatoly Zverev, Russian expressionist whom he met in the 1950s. Costakis said about Zverev "it was a source of great happiness for me to come into contact with this wonderful artist, and I believe him to be one of the most talented artists in Soviet Russia."

By the 1960 the apartment of George Costakis in Moscow had become a meeting place for international art collectors and art lovers in general: Russia's unofficial Museum of Modern Art. The 'détente' period following the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973 opened up Russia once again to international cultural exchanges the first of which was the showing of the Costakis Collection in Düsseldorf in 1977.

The same year Costakis, with his family, left the Soviet Union and moved to Greece, but there was an agreement that he should leave 50 per cent of his collection in the State Tretyakov Gallery of Moscow. In 1997 the Greek State bought the remaining 1,275 works. They are now a part of the permanent collection of the State Museum of Contemporary Art, in Thessaloniki, Greece.

Beginnings

[edit]

Constructivism was a post-World War I development of Russian Futurism, and particularly of the 'counter reliefs' of Vladimir Tatlin, which had been exhibited in 1915. The term itself was invented by the sculptors Antoine Pevsner and Naum Gabo, who developed an industrial, angular style of work, while its geometric abstraction owed something to the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich. Constructivism first appears as a term in Gabo's Realistic Manifesto of 1920. Aleksei Gan used the word as the title of his book Constructivism, printed in 1922.[3]

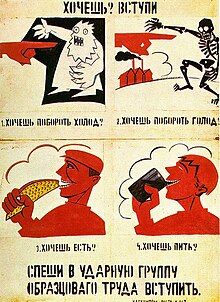

構成主義是二十世紀初的一場藝術運動,由弗拉基米爾·塔特林和亞歷山大·羅德欽科於 1915 年創立。[ 1 ]抽象而樸素的建構主義藝術旨在反映現代工業社會和城市空間。[ 1 ]運動拒絕裝飾風格,轉而支持工業材料組合。[ 1 ]構成主義者贊成將藝術用於宣傳和社會目的,並與蘇聯社會主義、布爾什維克和俄羅斯前衛派聯繫在一起。[ 2 ]

建構主義作為理論和實踐,很大程度上源自於1920年至 1922 年莫斯科藝術文化研究所( INKhUK )的一系列辯論。斯寧(Alexander Vesnin)、羅德琴科(Rodchenko)、瓦爾瓦拉·斯特潘諾娃(Varvara Stepanova)以及理論家阿列克謝·甘(Aleksei Gan)、鮑里斯·阿爾瓦托夫(Boris Arvatov )和奧西普·布里克(Osip Brik))將建構主義定義為“faktura”(物體的特定材料屬性)和“tektonika”(物體的特定材料屬性)的組合。最初,構成主義者將三維結構作為參與工業的一種手段:OBMOKhU(青年藝術家協會)展覽展示了由 Rodchenko、Stepanova、Karl Ioganson和Stenberg 兄弟創作的三維作品。後來,這個定義擴展到書籍或海報等二維作品的設計,蒙太奇和事實記錄成為重要的概念。

Constructivism as theory and practice was derived largely from a series of debates at the Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK) in Moscow, from 1920 to 1922. After deposing its first chairman, Wassily Kandinsky, for his 'mysticism', The First Working Group of Constructivists (including Liubov Popova, Alexander Vesnin, Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and the theorists Aleksei Gan, Boris Arvatov and Osip Brik) would develop a definition of Constructivism as the combination of faktura: the particular material properties of an object, and tektonika, its spatial presence. Initially the Constructivists worked on three-dimensional constructions as a means of participating in industry: the OBMOKhU (Society of Young Artists) exhibition showed these three dimensional compositions, by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Karl Ioganson and the Stenberg brothers. Later the definition would be extended to designs for two-dimensional works such as books or posters, with montage and factography becoming important concepts.

Art in the service of the Revolution

[edit]

As much as involving itself in designs for industry, the Constructivists worked on public festivals and street designs for the post-October revolution Bolshevik government. Perhaps the most famous of these was in Vitebsk, where Malevich's UNOVIS Group painted propaganda plaques and buildings (the best known being El Lissitzky's poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919)). Inspired by Vladimir Mayakovsky's declaration 'the streets our brushes, the squares our palettes', artists and designers participated in public life during the Civil War. A striking instance was the proposed festival for the Comintern congress in 1921 by Alexander Vesnin and Liubov Popova, which resembled the constructions of the OBMOKhU exhibition as well as their work for the theatre. There was a great deal of overlap during this period between Constructivism and Proletkult, the ideas of which concerning the need to create an entirely new culture struck a chord with the Constructivists. In addition some Constructivists were heavily involved in the 'ROSTA Windows', a Bolshevik public information campaign of around 1920. Some of the most famous of these were by the poet-painter Vladimir Mayakovsky and Vladimir Lebedev.

The constructivists tried to create works that would make the viewer an active viewer of the artwork. In this it had similarities with the Russian Formalists' theory of 'making strange', and accordingly their main theorist Viktor Shklovsky worked closely with the Constructivists, as did other formalists like the Arch Bishop. These theories were tested in theatre, particularly with the work of Vsevolod Meyerhold, who had established what he called 'October in the theatre'. Meyerhold developed a 'biomechanical' acting style, which was influenced both by the circus and by the 'scientific management' theories of Frederick Winslow Taylor. Meanwhile, the stage sets by the likes of Vesnin, Popova and Stepanova tested Constructivist spatial ideas in a public form. A more populist version of this was developed by Alexander Tairov, with stage sets by Aleksandra Ekster and the Stenberg brothers. These ideas would influence German directors like Bertolt Brecht and Erwin Piscator, as well as the early Soviet cinema.

Tatlin, 'Construction Art' and Productivism

[edit]The key work of Constructivism was Vladimir Tatlin's proposal for the Monument to the Third International (Tatlin's Tower) (1919–20)[4] which combined a machine aesthetic with dynamic components celebrating technology such as searchlights and projection screens. Gabo publicly criticised Tatlin's design saying, "Either create functional houses and bridges or create pure art, not both." This had already caused a major controversy in the Moscow group in 1920 when Gabo and Pevsner's Realistic Manifesto asserted a spiritual core for the movement. This was opposed to the utilitarian and adaptable version of Constructivism held by Tatlin and Rodchenko. Tatlin's work was immediately hailed by artists in Germany as a revolution in art: a 1920 photograph shows George Grosz and John Heartfield holding a placard saying 'Art is Dead – Long Live Tatlin's Machine Art', while the designs for the tower were published in Bruno Taut's magazine Frühlicht. The tower was never built, however, due to a lack of money following the revolution.[5]

Tatlin's tower started a period of exchange of ideas between Moscow and Berlin, something reinforced by El Lissitzky and Ilya Ehrenburg's Soviet-German magazine Veshch-Gegenstand-Objet which spread the idea of 'Construction art', as did the Constructivist exhibits at the 1922 Russische Ausstellung in Berlin, organised by Lissitzky. A Constructivist International was formed, which met with Dadaists and De Stijl artists in Germany in 1922. Participants in this short-lived international included Lissitzky, Hans Richter, and László Moholy-Nagy. However the idea of 'art' was becoming anathema to the Russian Constructivists: the INKhUK debates of 1920–22 had culminated in the theory of Productivism propounded by Osip Brik and others, which demanded direct participation in industry and the end of easel painting. Tatlin was one of the first to attempt to transfer his talents to industrial production, with his designs for an economical stove, for workers' overalls and for furniture. The Utopian element in Constructivism was maintained by his 'letatlin', a flying machine which he worked on until the 1930s.

Constructivism and consumerism

[edit]In 1921, the New Economic Policy was established in the Soviet Union, which opened up more market opportunities in the Soviet economy. Rodchenko, Stepanova, and others made advertising for the co-operatives that were now in competition with other commercial businesses. The poet-artist Vladimir Mayakovsky and Rodchenko worked together and called themselves "advertising constructors". Together they designed eye-catching images featuring bright colours, geometric shapes, and bold lettering. The lettering of most of these designs was intended to create a reaction, and function emotionally – most were designed for the state-owned department store Mosselprom in Moscow, for pacifiers, cooking oil, beer and other quotidian products, with Mayakovsky claiming that his 'nowhere else but Mosselprom' verse was one of the best he ever wrote. Additionally, several artists tried to work with clothes design with varying success: Varvara Stepanova designed dresses with bright, geometric patterns that were mass-produced, although workers' overalls by Tatlin and Rodchenko never achieved this and remained prototypes. The painter and designer Lyubov Popova designed a kind of Constructivist flapper dress before her early death in 1924, the plans for which were published in the journal LEF. In these works, Constructivists showed a willingness to involve themselves in fashion and the mass market, which they tried to balance with their Communist beliefs.

LEF and Constructivist cinema

[edit]The Soviet Constructivists organised themselves in the 1920s into the 'Left Front of the Arts', who produced the influential journal LEF, (which had two series, from 1923 to 1925 and from 1927 to 1929 as New LEF). LEF was dedicated to maintaining the avant-garde against the critiques of the incipient Socialist Realism, and the possibility of a capitalist restoration, with the journal being particularly scathing about the 'NEPmen', the capitalists of the period. For LEF the new medium of cinema was more important than the easel painting and traditional narratives that elements of the Communist Party were trying to revive then. Important Constructivists were very involved with cinema, with Mayakovsky acting in the film The Young Lady and the Hooligan (1919), Rodchenko's designs for the intertitles and animated sequences of Dziga Vertov's Kino Eye (1924), and Aleksandra Ekster designs for the sets and costumes of the science fiction film Aelita (1924).

The Productivist theorists Osip Brik and Sergei Tretyakov also wrote screenplays and intertitles, for films such as Vsevolod Pudovkin's Storm over Asia (1928) or Victor Turin's Turksib (1929). The filmmakers and LEF contributors Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein as well as the documentarist Esfir Shub also regarded their fast-cut, montage style of filmmaking as Constructivist. The early Eccentrist movies of Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg (The New Babylon, Alone) had similarly avant-garde intentions, as well as a fixation on jazz-age America which was characteristic of the philosophy, with its praise of slapstick-comedy actors like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, as well as of Fordist mass production. Like the photomontages and designs of Constructivism, early Soviet cinema concentrated on creating an agitating effect by montage and 'making strange'.

Photography and photomontage

[edit]Although originated in Germany, photomontage was a popular art form for Constructivists to create visually striking art and a method to convey change; "[6]". The Constructivists were early developers of the techniques of photomontage. Gustav Klutsis' 'Dynamic City' and 'Lenin and Electrification' (1919–20) are the first examples of this method of montage, which had in common with Dadaism the collaging together of news photographs and painted sections. Lissitzky's 'The Constructor' is one of many examples of photomontage that utilises photo collage to create a multi-layer composition. This brought forth the Constuctor's artistic vision and technique of utilising 2D space with limited technology. However Constructivist montages would be less 'destructive' than those of Dadaism. Perhaps the most famous of these montages was Rodchenko's illustrations of the Mayakovsky poem About This.

LEF also helped popularise a distinctive style of photography, involving jagged angles and contrasts and abstract use of light, which paralleled the work of László Moholy-Nagy in Germany: The major practitioners of this included, along with Rodchenko, Boris Ignatovich and Max Penson, among others. Kulagina, collaborating with Klutiso, utilised the use of photomontage to create political and personal posters of representative subjects from women in the workforce to satirise the humour of the local government. This also shared many characteristics with the early documentary movement.

Constructivist graphic design

[edit]

The book designs of Rodchenko, El Lissitzky and others such as Solomon Telingater and Anton Lavinsky were a major inspiration for the work of radical designers in the West, particularly Jan Tschichold. Many Constructivists worked on the design of posters for everything from cinema to political propaganda: the former represented best by the brightly coloured, geometric posters of the Stenberg brothers (Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg), and the latter by the agitational photomontage work of Gustav Klutsis and Valentina Kulagina.

In Cologne in the late 1920s Figurative Constructivism emerged from the Cologne Progressives, a group which had links with Russian Constructivists, particularly Lissitzky, since the early twenties. Through their collaboration with Otto Neurath and the Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum such artists as Gerd Arntz, Augustin Tschinkel and Peter Alma affected the development of the Vienna Method. This link was most clearly shown in A bis Z, a journal published by Franz Seiwert, the principal theorist of the group.[7] They were active in Russia working with IZOSTAT and Tschinkel worked with Ladislav Sutnar before he emigrated to the US.

The Constructivists' main early political patron was Leon Trotsky, and it began to be regarded with suspicion after the expulsion of Trotsky and the Left Opposition in 1927–28. The Communist Party would gradually favour realist art during the course of the 1920s (as early as 1918 Pravda had complained that government funds were being used to buy works by untried artists). However it was not until about 1934 that the counter-doctrine of Socialist Realism was instituted in Constructivism's place. Many Constructivists continued to produce avant-garde work in the service of the state, such as Lissitzky, Rodchenko and Stepanova's designs for the magazine USSR in Construction.

Constructivist architecture

[edit]

Constructivist architecture emerged from the wider constructivist art movement. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, it turned its attentions to the new social demands and industrial tasks required of the new regime. Two distinct threads emerged, the first was encapsulated in Antoine Pevsner's and Naum Gabo's Realist manifesto which was concerned with space and rhythm, the second represented a struggle within the Commissariat for Enlightenment between those who argued for pure art and the Productivists such as Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova and Vladimir Tatlin, a more socially oriented group who wanted this art to be absorbed in industrial production.[8]

A split occurred in 1922 when Pevsner and Gabo emigrated. The movement then developed along socially utilitarian lines. The productivist majority gained the support of the Proletkult and the magazine LEF, and later became the dominant influence of the architectural group O.S.A., directed by Alexander Vesnin and Moisei Ginzburg.

Artistic periods

[edit]Kandinsky's creation of abstract work followed a long period of development and maturation of intense thought based on his artistic experiences. He called this devotion to inner beauty, fervor of spirit and spiritual desire "inner necessity";[8] it was a central aspect of his art. Some art historians suggest that Kandinsky's passion for abstract art began when one day, coming back home, he found one of his own paintings hanging upside down in his studio and he stared at it for a while before realizing it was his own work,[9] suggesting to him the potential power of abstraction.

In 1896, at the age of 30, Kandinsky gave up a promising career teaching law and economics to enroll in the Munich Academy where his teachers would eventually include Franz von Stuck.[10] He was not immediately granted admission and began learning art on his own. That same year, before leaving Moscow, he saw an exhibit of paintings by Monet. He was particularly taken with the impressionistic style of Haystacks; this, to him, had a powerful sense of colour almost independent of the objects themselves. Later, he would write about this experience:

Kandinsky was similarly influenced during this period by Richard Wagner's Lohengrin which, he felt, pushed the limits of music and melody beyond standard lyricism.[12] He was also spiritually influenced by Madame Blavatsky (1831–1891), the best-known exponent of theosophy. Theosophical theory postulates that creation is a geometrical progression, beginning with a single point. The creative aspect of the form is expressed by a descending series of circles, triangles, and squares. Kandinsky's book Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1910) and Point and Line to Plane (1926) echoed this theosophical tenet. Illustrations by John Varley in Thought-Forms (1901) influenced him visually.[13]

Metamorphosis

[edit]

In the summer of 1902, Kandinsky invited Gabriele Münter to join him at his summer painting classes just south of Munich in the Alps. She accepted the offer and their relationship became more personal than professional. Art school, usually considered difficult, was easy for Kandinsky. It was during this time that he began to emerge as an art theorist as well as a painter. The number of his existing paintings increased at the beginning of the 20th century; much remains of the landscapes and towns he painted, using broad swaths of colour and recognisable forms. For the most part, however, Kandinsky's paintings did not feature any human figures; an exception is Sunday, Old Russia (1904), in which Kandinsky recreates a highly colourful (and fanciful) view of peasants and nobles in front of the walls of a town. Couple on Horseback (1907) depicts a man on horseback, holding a woman as they ride past a Russian town with luminous walls across a blue river. The horse is muted while the leaves in the trees, the town, and the reflections in the river glisten with spots of colour and brightness. This work demonstrates the influence of pointillism in the way the depth of field is collapsed into a flat, luminescent surface. Fauvism is also apparent in these early works. Colours are used to express Kandinsky's experience of subject matter, not to describe objective nature.

Perhaps the most important of his paintings from the first decade of the 1900s was The Blue Rider (1903), which shows a small cloaked figure on a speeding horse rushing through a rocky meadow. The rider's cloak is medium blue, which casts a darker-blue shadow. In the foreground are more amorphous blue shadows, the counterparts of the fall trees in the background. The blue rider in the painting is prominent (but not clearly defined), and the horse has an unnatural gait (which Kandinsky must have known) [citation needed]. This intentional disjunction, allowing viewers to participate in the creation of the artwork, became an increasingly conscious technique used by Kandinsky in subsequent years; it culminated in the abstract works of the 1911–1914 period. In The Blue Rider, Kandinsky shows the rider more as a series of colours than in specific detail. This painting is not exceptional in that regard when compared with contemporary painters, but it shows the direction Kandinsky would take only a few years later.

From 1906 to 1908, Kandinsky spent a great deal of time travelling across Europe (he was an associate of the Blue Rose symbolist group of Moscow) until he settled in the small Bavarian town of Murnau. In 1908, he bought a copy of Thought-Forms by Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater. In 1909, he joined the Theosophical Society. The Blue Mountain (1908–1909) was painted at this time, demonstrating his trend toward abstraction. A mountain of blue is flanked by two broad trees, one yellow and one red. A procession, with three riders and several others, crosses at the bottom. The faces, clothing, and saddles of the riders are each a single color, and neither they nor the walking figures display any real detail. The flat planes and the contours also are indicative of Fauvist influence. The broad use of color in The Blue Mountain illustrates Kandinsky's inclination toward an art in which colour is presented independently of form, and in which each color is given equal attention. The composition is more planar; the painting is divided into four sections: the sky, the red tree, the yellow tree, and the blue mountain with the three riders.

Blue Rider Period (1911–1914)

[edit]

Kandinsky's paintings from this period are large, expressive coloured masses evaluated independently from forms and lines; these serve no longer to delimit them, but overlap freely to form paintings of extraordinary force. Music was important to the birth of abstract art since it is abstract by nature; it does not try to represent the exterior world, but expresses the inner feelings of the soul in an immediate way. Kandinsky sometimes used musical terms to identify his works; he called his most spontaneous paintings "improvisations" and described more elaborate works as "compositions."

In addition to painting, Kandinsky was an art theorist; his influence on the history of Western art stems perhaps more from his theoretical works than from his paintings. He helped found the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (Munich New Artists' Association), becoming its president in 1909. However, the group could not integrate the radical approach of Kandinsky (and others) with conventional artistic concepts and the group dissolved in late 1911. Kandinsky then formed a new group, The Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) with like-minded artists such as August Macke, Franz Marc, Albert Bloch, and Gabriele Münter. The group released an almanac (The Blue Rider Almanac) and held two exhibits. More of each were planned, but the outbreak of World War I in 1914 ended these plans and sent Kandinsky back to Russia via Switzerland and Sweden.

His writing in The Blue Rider Almanac and the treatise "On the Spiritual in Art" (which was released in 1910) were both a defence and promotion of abstract art and an affirmation that all forms of art were equally capable of reaching a level of spirituality. He believed that colour could be used in a painting as something autonomous, apart from the visual description of an object or other form.

These ideas had an almost-immediate international impact, particularly in the English-speaking world.[14] As early as 1912, On the Spiritual in Art was reviewed by Michael Sadleir in the London-based Art News.[15] Interest in Kandinsky grew quickly when Sadleir published an English translation of On the Spiritual in Art in 1914. Extracts from the book were published that year in Percy Wyndham Lewis's periodical Blast, and Alfred Orage's weekly cultural newspaper The New Age. Kandinsky had received some notice earlier in Britain, however; in 1910, he participated in the Allied Artists' Exhibition (organised by Frank Rutter) at London's Royal Albert Hall. This resulted in his work being singled out for praise in a review of that show by the artist Spencer Frederick Gore in The Art News.[16]

Sadleir's interest in Kandinsky also led to Kandinsky's first works entering a British art collection; Sadleir's father, Michael Sadler, acquired several wood-prints and the abstract painting Fragment for Composition VII in 1913 following a visit by father and son to meet Kandinsky in Munich that year. These works were displayed in Leeds, either in the university or the premises of the Leeds Arts Club, between 1913 and 1923.[17]

Return to Russia (1914–1921)[edit]

In Grey (1919) by Kandinsky, exhibited at the 19th State Exhibition, Moscow, 1920

In Grey (1919) by Kandinsky, exhibited at the 19th State Exhibition, Moscow, 1920The sun melts all of Moscow down to a single spot that, like a mad tuba, starts all of the heart and all of the soul vibrating. But no, this uniformity of red is not the most beautiful hour. It is only the final chord of a symphony that takes every colour to the zenith of life that, like the fortissimo of a great orchestra, is both compelled and allowed by Moscow to ring out.

— Wassily Kandinsky[20]

From 1918 to 1921, Kandinsky was involved in the cultural politics of Russia and collaborated in art education and museum reform. He painted little during this period, but devoted his time to artistic teaching with a program based on form and colour analysis; he also helped organize the Institute of Artistic Culture in Moscow (of which he was its first director). His spiritual, expressionistic view of art was ultimately rejected by the radical members of the institute as too individualistic and bourgeois. In 1921, Kandinsky was invited to go to Germany to attend the Bauhaus of Weimar by its founder, architect Walter Gropius.

Back in Germany and the Bauhaus (1922–1933)

******

2022.04【#Art and Design 國際週報】005:俄國傳奇藝術品收藏故事,以H. Matisse 作品為主: Collecting Matisse. Voyage into Myth. The Collections Of Sergei Shchukin And Ivan Morozov. Matisse and Russian Icons

這張的收藏史很可能是屬於"俄國傳奇藝術品收藏故事"。

By Henri Matisse.French painter

Pushkin Museum of Fine Art/Mosco

9. The Morozov Collection

In autumn the Fondation Louis Vuitton presents masterpieces from the collections of Mikhail and Ivan Morozov, Russian brothers and entrepreneurs who amassed a treasure trove of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist work before the Revolution: an astonishing assortment of Monets and Matisses, Pissarros and Picassos. They were more discriminating even than their contemporaries Sergei and Pyotr Shchukin, whose own horde of avant-garde wonders wowed the art world at the Fondation in 2016. KG

【#Art and Design 國際週報】005:俄國傳奇藝術品收藏故事,以H. Matisse 作品為主: Collecting Matisse. Voyage into Myth. The Collections Of Sergei Shchukin And Ivan Morozov. Matisse and Russian Icons

1987年Henri Matisse (1869~1954)的兒子Pierre Matisse (1900~89)

和孫女,特地去聖彼得堡的"冬宮博物館 Hermitage Museum

"看父親/祖父為媽媽/嬤嬤的的畫像。

俄國傳奇藝術品收藏故事,以H. Matisse 作品為主: Collecting Matisse. Voyage into Myth. The Collections Of Sergei Shchukin And Ivan Morozov. Matisse and Russian Icons

讀Voyage into Myth (2002 )第四章

Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov :Two Legendary Collectors

Voyage Into Myth: French Painting from Gauguin to Matisse from the Hermitage Museum 平裝 – 2002

Nathalie & Francine Lavoie (curators) Bondil (Author), Profusely illustrated (Illustrator)

***

查看該圖像

查看該圖像"The Dessert: Harmony in Red" (The Red Room ) 1908 Matisse’s Fauvist period.🎨🇲🇫️ Oil on canvas 180,5x221 cm Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.🏛️️🇷🇺️ In his Paris studio with its windows looking out over a monastery garden, in 1908 Matisse created one of his most important works of the period 1908-1913: "The Red Room". The artist himself called this a "decorative panel" and it was intended for the dining room in the Moscow mansion of the famous Russian collector Sergey Shchukin. Matisse turned to a motif common in the works created that year: a room decorated with vases, fruits and flowers.

Collecting Matisse (English) Hardcover – 三月 17, 1999

Rizzoli (Author)

Relying on his sensibility and self-confidence, Shchukin confronted a Russian society that ridiculed his eccentricities, and from 1908 to 1914 he assembled an exceptional collection of Matisse's works - thirty-seven paintings - with which he decorated his house in Moscow. Morozov was equally appreciative of the painter and, although a more modest collector, acquired eleven canvases. Between them, these two men made Russia the first foreign country to import Matisse's works.

Collecting Matisse provides a fresh interpretation of a crucial period in the artist's career - the early years of Fauvism, when he decisively turned toward color as the essential element of painting - and one that radically marked the development of modern art as a whole. Matisse's work was known in Russia as early as 1904, and Shchukin's commission for the great decorative panels La Danse and La Musique revolutionized the Moscow art world. A penetrating text and previously unpublished archival material make this book an essential study on Matisse and his 1911 visit to Russia, where he discovered with fascination Russian icons, tasted the delights of the salons, and unleashed the commentaries of a hostile press, which are included here in large extracts. The following year, Matisse left for Tangier and there produced a stunning series of canvases, which the two Russian collectors acquired with enthusiasm. The correspondence published here for the first time, bears eloquent testimony to the ties of friendship and admiration that united painter and collectors.

The beautiful illustrations and rare period photographs of the Shchukin and Morozov mansions and collections complement the impressions Matisse gathered in the Russian capital and demonstrate their importance for the evolution of his art.

Contents

The Morozov Brothers. Great Russian Collectors - Hermitage

Matisse arrived in Moscow on October 23, 1911. The next day, he visited Ilya Ostroukhov, painter and collector and "patron" of the Tretiakov Gallery, whom he had met in Paris, and asked to be shown his collection of Russian Icons. A day later Oustroukhov recounted the incident:

"Yesterday evening he visited us. And you should have seen his delight at the icons. Literally the whole evening he

wouldn't leave them alone, relishing and delighting in each one. And with what finesse! ... At length he declared that

for the icons alone it would have been worth his while coming from a city even further away than Paris, that the icons

were now nobler for him than Fra Beato... Today Shchukin phoned me to say that Matisse literally could not sleep

the whole night because of the acuity of his impression."[6]

"From that moment on, "writes Pierre Schneider, "Matisse spent all his time going around to visit churches, convents, and collections of sacred images, his excitement at the first encounter not having diminished one iota. He shared it with all who came to interview him during his stay in Moscow." [7]

On Oct. 31, Ilya Ostroukhov wrote to D.J. Tolstoy, the curator of the Hermitage Museum: "Matisse is here. He is deeply affected by the art of the icons. He seems overwhelmed and is spending his days with me frantically visiting monasteries, churches and private collections." [8]

"They are really great art," Matisse excitedly told an interviewer. "I am in love with their moving simplicity which, to me, is closer and dearer than Fra Angelico. In these icons the soul of the artist who painted them opens out like a mystical flower. And from them we ought to learn how to understand art." [9] What is one to make of this expression of heartfelt admiration for the old Russian icons? From these icons "we ought to learn how to understand art." This is a very strong statement. It sounds exaggerated. Yet, Matisse was habitually reserved and cautious in his statements, not prone to exaggeration. Our endeavor in these pages may be defined as an investigation of the meaning and validity of this assertion.

"From them we ought to learn how to understand art." Not one particular kind of art, but art in itself. The icons offered Matisse a revelation of what art is. This goes deeper than stylistic "influence." To speak of Matisse imitating or being influenced by icons is to miss the point. His relationship with them is on a deeper level. In them he has recognized, in an especially pure form, the essence of art. Art is, for Matisse, essentially a manifestation of the life in which both nature and the artist participate. Throughout his career Matisse was a truly original artist. This does not mean that one cannot find in his work what are commonly called "influences" of other artists, in this case the Russian iconographers. It means that Matisse's art is directly rooted in the place where art originates, in the wellspring of being which we mentioned at the beginning. Precisely because he strives to be true to nature, Matisse converges with the icon painters.

![Untitled First Abstract Watercolor, 1910–1913, Centre Pompidou, Paris[18]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/79/Untitled_%28First_Abstract_Watercolor%29_by_Wassily_Kandinsky.jpg/120px-Untitled_%28First_Abstract_Watercolor%29_by_Wassily_Kandinsky.jpg)

![Mit Dem Schwarzen Boden, 1912, Centre Pompidou, Paris[19]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d2/Vassily_kandinsky%2C_con_l%27arco_nero%2C_1912.JPG/120px-Vassily_kandinsky%2C_con_l%27arco_nero%2C_1912.JPG)

沒有留言:

張貼留言